Owning and flying your own airplane brings with it a variety of levels of responsibility. As the owner, operator and pilot, there can be no doubt as to who has the responsibility for ensuring proper maintenance, correct operation and full pilot proficiency.

The legal responsibility is only a small part of the picture. Youre also responsible for yourself as well as the well-being of those who entrust their lives to you as passengers.

The problem is that some pilots forget those simple facts. Instead, they get caught up in impressing their passengers with their proficiency or the airplanes capabilities. Speedy departures, rather than thorough preflight planning and inspection, become goals toward which they aspire. They want to carry all of the passengers and all of their bags with as few fuel stops as possible, even if that means blurring the lines of the weight and balance envelope.

If you fly long enough, youll bump into all of the limitations of both yourself and your airplane. Sometimes youll step a bit over the line, learn something, and resolve to be more conscientious next time. But if your mistakes are grave enough or your timing bad enough, you may not have that opportunity.

One such victim was the owner and pilot of a Beech 55 Baron. He called Flight Service for a weather briefing one Friday morning in May for a planned trip from the San Antonio suburbs to the Corpus Christi suburbs. There he would pick up passengers and fly to Houston, where another passenger would board. From there, the six men were headed for a fishing trip in Galliano, La., a small town on the Mississippi River delta south of New Orleans. The pilot filed IFR flight plans for each leg of the trip.

The first two legs of the flight went without incident and the airplane landed at Houston Hobby airport shortly after 11 a.m. He taxied to the Raytheon Aircraft Services FBO and ordered the main tanks topped off and 10 gallons added to each auxiliary tank. The pilot asked the ramp personnel for a quick turnaround and a passenger paid the fuel bill for 45 gallons about 20 minutes later at 11:36.

Witnesses at the FBO said all six men were in good spirits talking about their trip. They piled into the airplane for takeoff. The pilot called clearance delivery at 11:45 and a minute later contacted ground control for taxi instructions. That call led to the following exchange:

Baron 05A, Hobby ground. Taxi via kilo and taxi runway 22.

Understand. Kilo down to 22. Thanks.

Baron 05A, you need a run-up or you be ready when you get there?

Well be ready when we get there.

Thirty seconds later the ground controller told the Baron pilot to monitor the tower. Another 30 seconds went by, at which point the tower controller cleared the Baron into position and hold on the runway. A minute later, at 11:50, the airplane was cleared for takeoff. The occupants had only a few seconds to live.

Several witnesses, on the ground and in the tower, said the airplane accelerated normally until it rotated to an extremely nose-high attitude, variously reported as 45 degrees to 80 degrees.

At least two witnesses said they knew a crash was imminent and began reacting even before it happened. One pilot on the ground started running to the site and a controller reached for the crash phone while the airplane was still in the air.

Hanging from its props at about 200 to 300 feet agl, the engines screaming at full power, the airplane suddenly stalled and rolled to the left, where it crashed just south of the taxiway that had just brought it to the runway. All six occupants were dead at the scene and thrown clear of the wreckage. A minute later, the wreckage began to burn.

Unraveling Clues

Inspection of the wreckage turned up no evidence of any mechanical problem with the airplane. What they did find was far more troubling.

Stuck into the control column was a gust lock pin. It wasnt a factory part, and a Beech analysis concluded it was either homemade or just a piece of the original gust lock pin. It had no warning flag and appeared to consist only of a pin that went into the bottom right of the control column and a clip to hold the pin to the column.

Well never know at what point the pilot discovered his error, or if there was any corrective action he could have taken to abort the takeoff. At some point during the takeoff but before the crash, he died of a heart attack.

While combing the wreckage, investigators found 12 metal weights, each weighing 10 pounds, in the forward baggage compartment. There was some evidence that the weights were ballast, presumably to counter the 55 Barons tendency toward an aft center of gravity. An acquaintance of the pilots said the ballast had even been figured into the empty aircraft weight on its current weight and balance sheet, but that could not be independently confirmed.

Using the known fuel load, the 40 pounds of luggage and the most favorable loading of occupants, investigators calculated that the airplane was either 230 pounds overweight with the cg a half inch aft of the aft limit, or 110 pounds overweight with the cg 1.8 inches aft, depending on whether the ballast was included as baggage or not. With a max takeoff weight of 5,100 pounds, either overloading seems relatively small for a twin with both engines operating, although the balance issue may have come into play if the ballast were included in the aircrafts empty weight.

Lock Logistics

The control lock rendered the weight and balance issue moot, and coming to terms with the presence of that particular lock requires something of a leap into human motivation.

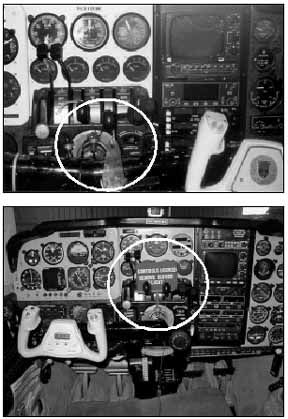

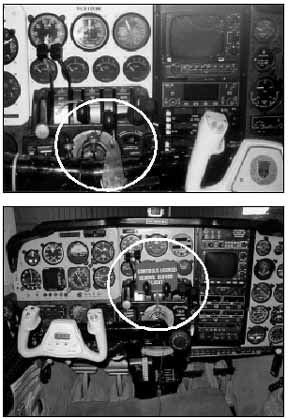

The 30-year-old aircrafts original control lock consisted of a control column pin, a securing clip, a throttle guard and a rudder lock pin. The control pin went through a hole in the column, and the clip held the pin in place. A cable passed through the pin and was attached to a red throttle guard. At the other end of the cable was a rudder lock pin.

The control locks many parts apparently were not well received. Two years after the airplane was built, Beech issued a safety communiqu in which it urged pilots to use the complete gust lock, not a makeshift one or only part of the approved part, and to check that the controls were free during preflight inspection.

Then in 1974, Beech issued a service instruction that recommended modifying the control lock installation by relocating the control lock hole location from the bottom of the control column to the top, and to position the hole two inches aft on the column. By moving the hole aft, the yoke would be farther forward when it was locked. A new control lock assembly was designed. Together, these changes would put the control column in a nose-down, right wing low position when the controls were locked.

In 1998, after Raytheon had purchased Beech, the company converted the voluntary service instruction to a Mandatory Service Bulletin that, despite its name, is not mandatory for Part 91 operations. The bulletin states that the new design and location will prevent throttle advancement with the control surface pin installed, make the properly installed lock impossible to overlook, and locks the flight control surfaces in positions which preclude rotation.

A review of the aircrafts maintenance records showed neither the service instruction nor the service bulletin had been complied with, a point that is obvious by virtue of the fact that the accident happened at all.

The question is why not.

Although the most recent pilot logbook investigators found ended in 1992, the pilot reported more than 4,100 hours total time, including nearly 750 in make and model.

As a successful roofing contractor, the pilot lived in a residential airpark with the airplane and maintained it according to an Approved Aircraft Inspection Program, which consists of four separate inspections every three months in lieu of an annual inspection.

Despite all of the inspections and his frequent use of the airplane, the service bulletin remained an afterthought.

Looking back at the accident, the extreme pitch up may have been partially induced by the aft center of gravity, especially if the airplane was not loaded in the best-case scenario used by investigators. Would the presence of the control lock merely have meant an embarrassing aborted takeoff if the loading had not been so extreme? Perhaps the controllers question about needing a runup induced the pilot to show his professionalism with a speedy departure. Most of all, whatever happened to controls free and correct?

Most pilots perform an abbreviated preflight inspection when they stop for only a few minutes while en route. The pilot should be applauded for using a shutdown checklist if thats what led to him installing the control lock when surface winds were only 8 knots. But if thats the case, why not use a before takeoff checklist?

In few other pursuits is it as true that the devil is in the details. But those details can rise up in rebellion given only the slightest of provocations.

Also With This Article

Click here to view “Confusing or Conspicuous?”

-by Ken Ibold