We were in IMC at 4000 feet, on a vector for the VOR-A approach at the Wichita, Kan., Colonel James Jabara Airport. The airplane was an A36 Bonanza and I was in the instructor’s seat on the last approach of a day-long training session. This was in the era before GPS, long before iPads and moving-map handhelds, and the owner of this then-well-equipped 36 had ignored the short-lived Loran phase. So we were eastbound on a long downwind, and crabbing into a northerly wind before intercepting the westbound final approach course before circling to Jabara’s north/south runway.

I was demonstrating how to maintain position awareness with the technology of the day: tuning the ADF to a beacon at Newton, a small airport about 20 miles almost due north of Jabara. From experience, I knew the ADF needle would point about 45 degrees behind the left wing around the time ATC would turn us south on a base leg, followed by a turn to intercept the final approach course inbound.

The ADF pointer was only slightly behind the left wing when we felt a sudden deceleration. I don’t recall the engine running roughly, but in retrospect it probably was. I do remember the pilot was initially in denial that an engine problem was happening; “It’s a brand new engine” he said at least once. So I took control of the decelerating airplane and began a level turn using the only positive indication I had of a place to land: I turned left until the ADF needle was pointing straight ahead at the airplane’s nose. I was “going direct” (homing, actually) to the beacon I knew was on the Newton airport.

With aircraft control (“fly the airplane,” or aviate) taken care of, I began to home (“navigate”) toward Newton. I then began to talk to my customer (“communicate”). I told the pilot aloud that we had an engine failure and directed him to do the first step of the Bonanza’s restart checklist: switch fuel tanks. The Bonanza’s LEFT/RIGHT/OFF fuel selector is below the pilot’s left knee and therefore invisible and out of reach from my seat. The pilot, who still was a bit shocked, switched the valve but it had no effect on engine power. I could reach the auxiliary fuel pump switch and mixture control to make the restart adjustments; by stretching I could check the magneto switch and, finally, I pulled the alternate air control—all to no effect. Meanwhile I keyed the microphone and called ATC (more “communicate”) to advise of the problem and our new destination.

“Bonanza 345, roger your power loss, are you declaring an emergency?” I’d meant to do that on the first transmission. “Affirmative, Wichita. Two persons and two hours of fuel on board.” I also told him I was able to maintain altitude for now. We were at 110 KIAS, the best glide speed of the A36. Best glide really means least drag, so it will net the best possible vertical performance for any given power level. In this case, I found full throttle, full rpm and best-power mixture for our altitude was just enough to maintain 4000 feet—any faster, any slower, or any throttle reduction and the airplane began to descend. It was a use of the best glide speed I’d not considered before.

My student had recovered from the “startle effect” and mentally caught up with the airplane, so I transferred control back to him while advising I would work the radios and direct his navigation. Without any way to tell the distance to Newton, I called ATC and asked; the controller told us we were seven miles out. Knowing the distance was close and the wind was from the north, I then asked the distance to Jabara. “Eight miles,” he replied. With the wind, the time would be about the same to either airport. And being an attended airport, I knew that rescue services would be available at Janara if I needed them. So I changed plans: “Thank you, Wichita. Give me a vector direct to the Jabara airport.” He did, and I made a level, standard-rate turn around to the south.

The controller then did what he undoubtedly thought would make things as easy as possible for me. Knowing the cloud bases were at about 2000 feet, well above minimums, he directed: “Descend and maintain 2000 feet; expect the visual approach at Jabara.” Knowing the engine could quit completely at any time, I didn’t want to lose any altitude until I had to. I replied, “Negative, Wichita, we’ll stay at 4000 for now. Tell me when we’re one mile from the airport and we’ll descend then.” I could spiral down over the airport if needed. ATC didn’t question my decision; when I was one mile out, he let me know and I descended beneath the clouds over the airport, spiraling down for a normal landing from there.

Ultimately, we found a fuel injection line had separated from a cylinder, resulting in loss of a cylinder and more than just one-sixth of our total power. More importantly, we were able to make that determination because we followed the axiom “aviate, navigate, then communicate,” in that order.

Abnormals in the clouds

As a Beech Bonanza/Baron simulator instructor, one of my favorite things was to put pilots in realistic decision-making scenarios and let them experience the impact of the choices they make. One such scenario involved a simulated flight from Wichita to Kansas City, Mo., roughly a one-hour flight in these airplanes. Prior to the “flight,” pilots were given simulated weather information—most looked at conditions at the departure and destination airport, and weather along a narrow path between the two airports. A weak cold front was just west of the route, creating marginal VMC at Wichita and Kansas City, with a forecast of IMC a couple of hours after the flight. The before-takeoff ATIS, however, had the weather degrading to IMC—the front was moving a little faster than expected. As we taught, we ensured the pilot had the approach chart available and briefed, and the backup radio frequencies tuned, for a return to the departure airport in case of emergency right after takeoff.

Except for a couple of teaching items I introduced, all went well until about halfway into the flight. For the Bonanza pilots, I then simulated a failed alternator. The Baron pilots saw a significant drop in oil pressure on an engine. The actual failure isn’t important; the idea was to present an abnormal procedure that had the potential to become an emergency if it got worse.

In more than four years of presenting this scenario, I found pilots were most likely to want to continue to Kansas City after recognizing and dealing with the problem. (For the alternator-out Bonanzas, this involved attempting an alternator reset and, when that didn’t work, activating a backup if available and then shedding electrical load. For the Barons, it was a precautionary engine shutdown and propeller feather. And they both found conditions at Kansas City had worsened sooner than forecast.

Baron pilots flew a single-engine approach to minimums, but the real fun was the Bonanza pilots. They soon depleted their battery and had to make a lost-comms, partial-panel approach after manually cranking down the landing gear. Some returned to Wichita only to find the airport below minimums. They had to choose between an emergency descent despite the weather, or climbing out under degraded aircraft systems to go somewhere else. A few of the pilots elected to go to Emporia, Kan., which was just ahead of the airplane when the abnormal occurred. Emporia was IMC with no radar service, requiring a full procedure nonprecision approach. (Yes, I was “that guy” as a simulator instructor.)

Almost no one called ATC and asked about conditions at airports other than directly along their route of flight. If they did ask, they learned that Salina, Kan., less than 100 miles northwest of the point where the failure occurred and possessing an 11,000-foot, tower-controlled runway, was under clear skies behind the weak, storm-free front. If only they had asked!

Commanding emergencies

One takeaway here is that ATC can be a tremendous resource during an emergency in IMC. Regardless of how much assistance a controller can provide—which will vary by the scenario—you are still pilot-in-command of the aircraft until you get it safely on the ground. Your responsibility for commanding emergencies in IMC is almost as old as flying itself. As already presented, this means the Big Three:

• Fly the airplane; ATC can’t do it for you—AVIATE.

• Aim toward an acceptable mitigation (an airport, improving weather, lower terrain)—NAVIGATE.

• Keep talking, to yourself and to ATC—COMMUNICATE.

There’s little more frightening to a pilot than the thought of an emergency in instrument meteorological conditions. To channel that fear into preparedness, think now about how you might respond to various emergencies in IMC and how you will use ATC’s help while you manage and command an emergency all the way to a successful landing.

Abnormal vs Emergency

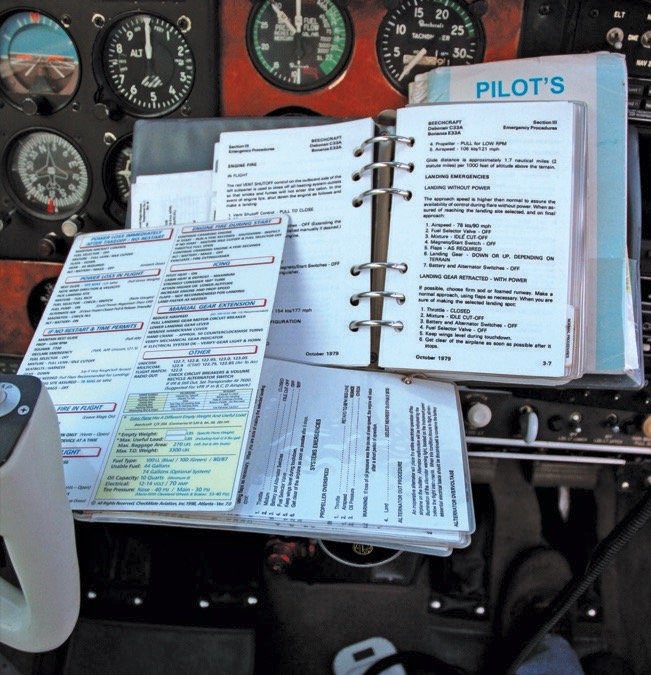

The airplane flight manual (AFM) for most turbine-powered aircraft make a distinction between emergency procedures and those that “just” address abnormalities. Some light piston airplane pilot’s operating handbooks (POHs) do the same, but most simply include the checklists for all systems malfunctions and errant indications into the emergency procedures section.

It’s helpful to consider the difference to be this: Emergency procedures are those that, because of the urgency of the situation involved or the speed and workload of its onset, include at least some steps that must be committed to memory and performed without referencing the emergency checklist. Examples include things like engine failures, trim runaways and electrical fires.

Abnormal procedures, by contrast, are system outages or indications that provide time to refer to the applicable AFM, POH or similar checklist. Examples of abnormal procedures are alternator failure, low oil pressure/high oil temperature conditions and landing gear malfunction.

You don’t have to memorize every checklist in the book, only those items that involve true emergencies when you must respond immediately and correctly.

That said, abnormal conditions and indications might be considered “impending emergencies.” If you don’t accomplish the checklist steps correctly, an “abnormal” will probably become an emergency. For instance, low oil pressure allowed to go too long will probably turn into an engine failure. An alternator out indication will eventually devolve into total electrical failure.

Although there is a delay, this makes abnormal conditions just as worthy of your expertise as outright emergencies, especially in IMC. Be ready to address emergencies by studying, memorizing and practicing true emergency procedures, and by knowing how to find and use abnormal procedures checklists when the situation calls for them.

Backups at the Ready, Please

Many pilots carry emergency backup equipment in case of a system outage in IMC. Common items include handheld communications radios with connections to an external airplane antenna, handheld GPS navigators and even Synthetic Vision Technology on iPads or other tablet device-based software. Most IFR airplanes have some level of panel-mounted backup flight instrumentation—most glass cockpit installations require it—such as a standby attitude indicator, airspeed and altimeter. All these backups are great and can significantly contribute to the safe outcome of your IFR flight in an emergency…if you are ready to use them.

Your iPad SVT may do you no good if it’s stuck in a bag you can’t reach in flight. You may not be able to fumble a handheld communications radio out of your flight bag, install batteries, hook up its external antenna connection and snap a headset adapter into place while bouncing around by reference to partial-panel instruments in an electrical failure. If your backup attitude indicator isn’t erect or your standby altimeter isn’t set, you might not be able to make the transition from the primaries. At the very least, it will take more work than it should while you are dealing with an abnormal or emergency condition.

Include arranging and powering up your handheld equipment in your pre-takeoff checks for an IFR flight. Keep the handheld comm charged and equipped with fresh batteries, and plug in its adapters and cables so all you’d have to do in an emergency is plug it into the external antenna jack and plug in your headset. Preflight your tablet device, clip it into its mount and start up the backup software before you take off. Ensure your backup attitude indicator agrees with your primary, and update the standby altimeter’s barometric setting every time you change the primary’s.

Just as important, practice using the backups with an instructor or safety pilot. I find that pilots feel a little disoriented even when using the reversionary mode of glass-panel indicators, for instance moving the primary flight display to the second, multifunction display on a G1000 panel. It takes practice with the backups to be ready to use them in an emergency in IMC.

Taking Command

Your strategy for commanding emergencies in IMC should be something like the following:

• Tell ATC you have an emergency and (briefly) what capabilities you have lost. This information can help controllers anticipate what other help you may need before the event is concluded. Voicing the situation aloud may also assist you mentally for the challenge of getting the airplane safely on the ground.

• Ask ATC for the help you need: weather reports, navigation assistance and/or airport, approach and runway information, etc.

• Tell ATC what you want to do and what you’re going to do. Consider the options controllers may present to you, but don’t delegate decision-making to someone who’s not aboard your aircraft.

• Ask ATC to watch over you, to monitor your progress, tell you if you are descending, turning or climbing unexpectedly, notify emergency responders at your new destination airport, etc.

Tom Turner is a CFII-MEI who frequently writes and lectures on aviation safety.