The NTSB in August released the latest in a series of what it calls Safety Alerts, which focused on preventable accidents stemming from fuel starvation or fuel exhaustion. According to the Safety Alert (SA-067, “Flying On Empty,” August 2017), an average of more than 50 accidents each year in the five years from 2011 to 2015 “occurred due to fuel management issues.” In a press release accompanying the Safety Alert, the NTSB added, “Fuel management is the sixth leading cause of general aviation accidents” in the U.S. and that pilot error “contributed to 95 percent of the fuel management related accidents.” Equipment issues contributed to five percent of the accidents during the period, according to the NTSB.

The Safety Alert includes some interesting observations, including that “student pilots were involved in just two percent of fuel-related accidents, while general aviation pilots holding either a commercial or air transport pilot certificate were involved in 48 percent of those accidents. Pilots holding private or sport pilot certificates were involved in the remaining 50 percent of fuel-related accidents.

Additionally, according to the NTSB, more than 66 percent of fuel management accidents occurred when the intent was to fly from one airport to another, as opposed to conducting a local flight. About 80 percent of fuel management accidents occurred in daytime VMC; only 15 percent occurred at night. The Safety Board noted that, “Pilot complacency and overestimation of flying ability can play a role in fuel management accidents.”

The Safety Alert noted that “Running out of fuel or starving an engine of fuel is highly preventable. An overwhelming majority of our investigations of fuel management accidents—95%— cited personnel issues (such as use of equipment, planning, or experience in the type of aircraft being flown) as causal or contributing to fuel exhaustion or starvation accidents. Prudent pilot action can eliminate these issues. Less than 5% of investigations cited a failure or malfunction of the fuel system.”

Probable-cause findings the NTSB cited in examining fuel-related accidents included statements like, “the pilot’s failure to reposition the fuel selector valve to the ON position prior to takeoff resulting in a loss of engine power due to fuel starvation. Contributing to the accident was the pilot’s failure to properly complete the pre-takeoff checklist.” Another one: “The probable cause of the accident was the pilot’s failure to adequately preflight the airplane prior to departure, which resulted in a loss of engine power due to fuel exhaustion.”

“The idea of running out of fuel in a car is an inconvenience. The idea of running out of fuel in an aircraft is unthinkable, and yet, it causes more accidents than anyone might imagine,” the NTSB noted. The Safety Alert also provided pointers to the March 2017 issue of the NASA Aviation Safety Reporting System’s Callback newsletter, an AOPA Safety Advisor publication on fuel management and this magazine’s article, “Fuel Systems 101,” which appeared in our January 2017 issue.

VFR Departure Procedures Revised At Aspen, Colo.

In a July 19, 2017, Letter to Airmen (LTA) from the Aspen, Colo., control tower, the FAA is advising operators of changes to VFR departure procedures at the facility. The LTA advises operators that a long-standing VFR procedure has been discontinued and details alternatives. “Due to elevation and terrain concerns, 90% of arriving aircraft land on Runway 15 and 95% of departing aircraft takeoff on Runway 33,” the LTA said.

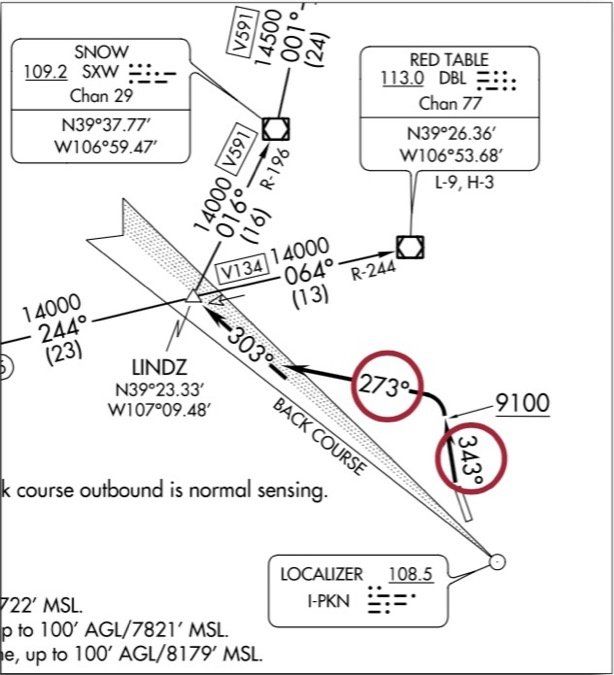

According to the LTA, a so-called “wrap procedure” had been develop locally to expedite the flow of traffic to and from the airport. That procedure called for the crew of the departing aircraft to anticipate and execute an initial right turn to a heading of 343 degrees, followed by a left turn to 273 degrees upon climbing out of 9100 feet msl on the LINDZ8 departure procedure. According to the LTA, “To ensure separation, controllers, at times, would alter the 273 turn timing to either expedite it when the aircraft climbed above 9100 feet msl or delay it until after traffic passed.” The field elevation at Aspen is 7838 feet.

In October 2016, the FAA began a review of the “wrap procedure” and “found issues with the practice,” according to the LTA. Subsequently, the “wrap procedure” was suspended on May 25, 2017.

Apparently, use of the “wrap procedure” greatly increased the number of operations at the facility since the LTA notes, “The FAA is reviewing the procedure and evaluating alternatives to return Aspen to normal operational arrival/departure rates as soon as possible. As a result, the airport’s IFR arrival/departure rates were reduced by 40%.”

That’s for VFR operations. For IFR flights departing Aspen, the same basic set of turns and altitude restrictions remain in effect when flying the LINDZ8 procedure. The difference, of course, is VFR separation criteria. The excerpt from the LINDZ8 departure procedure below highlights how the “wrap procedure” looks when charted.

Let’s all be careful there, okay?