I’ve long wanted regular access to a tube-and-fabric taildragger, something to fly low and slow, with my arm hanging out the window. I’m happy with my go-places airplane, which fits most of my missions, but variety is a good thing. A few flights in a friend and neighbor’s nice, simple, original Aeronca 7AC Champ didn’t whet my appetite for that kind of flying. Instead, it was stronger than ever. So when another friend emailed me a link to an auction for a similar airplane, with the simple question, “Halfsies?” the deal was all but done. A couple of weeks later, there literally was a used Champ on my door step.

There was one small problem: I had never flown a Champ as pilot-in-command. I had lots of time in similar airplanes—Super Cubs on straight floats, mainly—but some of that was as self-loading freight. I had logged 0.5 hour PIC in a wheel-equipped Cub one Sunday afternoon decades ago and was grandfathered from needing a specific endorsement, so I was legal to solo a taildragger. But I had enough conventional-gear/taildragger experience in other airplanes, including Decathlons and J-3 Cubs, to understand I didn’t know what I was doing, and needed some dual. After airplane readiness, weather and instructor schedules aligned themselves, I finally got enough stick time in Champs to figure out most of it. Here’s what a Debonair driver learned about taildraggers.

Differences

At max gross, my Debonair weighs 3550 lbs. Empty, it weighs 2200 lbs. Which is still more than this Champ at its max gross of 1300 lbs., or slightly less than the FAA’s light sport aircraft maximum weight of 1320 lbs. Understanding and considering the difference in the two airplanes’ weight was the first step I took toward transitioning. On a calm day, the weight difference doesn’t really mean anything, of course. But any wind at all is a consideration in a light airplane. Same for turbulence. That it’s a taildragger just adds to the…allure.

Aloft in benign conditions, the Champ is just another airplane: Pull back to make the houses look smaller. Finding the right sight picture takes a few minutes, as it does with any aircraft different from what you’re accustomed. Enthusiastic rudder use helps keep the ball centered (but when you’re cruising at 80 knots, who really cares?), and there are no wing flaps. The systems are simple and the gear is always down and locked. All in all, once the thing is airborne, it flies pretty much like it looks: unhurriedly. But the elephant in the room—sitting next to an 800-lb. gorilla—is ground handling.

Other Differences

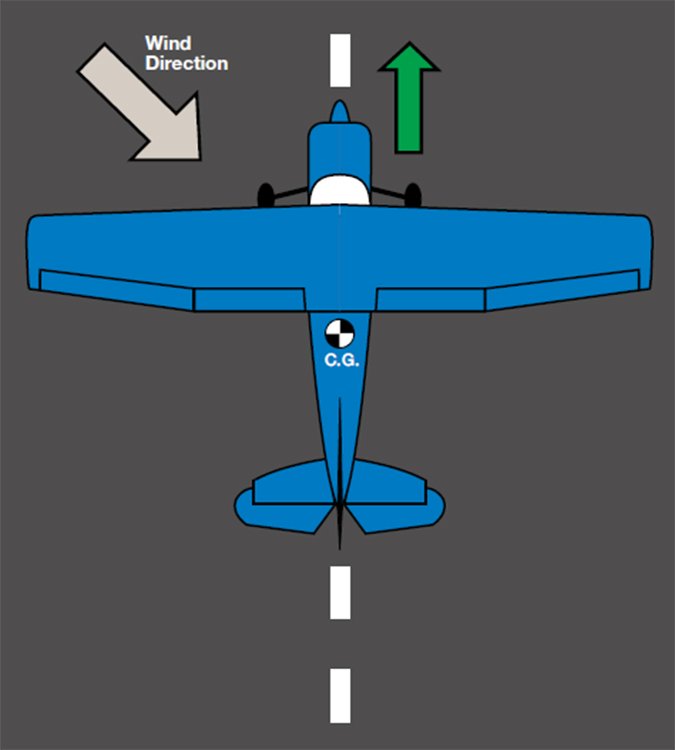

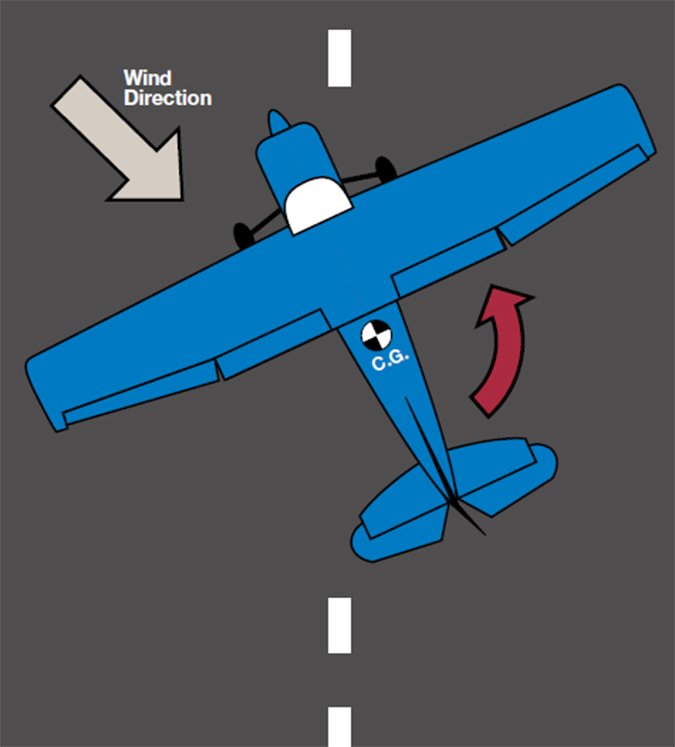

Intellectually, I know that putting the little wheel at the tail instead of under the nose wreaks all kinds of havoc with ground handling characteristics. Because a taildragger’s main gear is farther forward than a similar tricycle-gear airplane’s mains, its center of gravity is aft of the big wheels. One result is the taildragger’s tendency to weathervane—point itself into the wind. And as we’ve discussed, there’s not that much weight to begin with, so even relatively calm breezes can be a factor. The punchline is that surface wind can be a major consideration when flying a taildragger. Putting that knowledge into use took some practice.

If there was any single thing for which I was unprepared, it’s how much concentration is required to safely and reliably taxi a taildragger. As it turns out, the Champ’s wingspan is roughly the same as the Debonair’s, so that’s not an issue. Similarly, the Champ’s cowling is low enough—and I’m tall enough—that I don’t have to S-turn my way down a taxiway to ensure I don’t hit anything. I can see to within 15 or 20 feet in front of the Champ when it’s at rest, about the same as the Debonair.

No—the problem is keeping the dang thing straight in the face of almost any breeze. The taildragger’s tendency to weathervane makes the taxi phase of flight much more interesting and entertaining than in a tricycle-gear airplane. Of particular interest should be the taildragger’s behavior when taxiing with a tailwind, especially a quartering tailwind. Think about it: the weathervaning tendency wants to point the airplane into the wind, but that’s opposite to the direction you need to taxi. Slow and steady wins the race, but often at the expense of brake linings and sore legs. And the patience of pilots behind you on the taxiway.

Runway Behavior

With all that in mind, the Champ’s runway behavior is relatively benign. Once you get it into position and—smoothly!—apply takeoff power, its momentum and inertia tend to work against any breezes or gusts trying to displace it sideways. With more air flowing over the rudder from the increasing airspeed and propwash, keeping things straight gets easier.

On landing, the opposite is true. My instructors prefer doing full-stall, three-point landings to get the tailwheel on the ground as soon as possible. The alternative is wheel landings, where the airplane touches down on the mains and then the tail is gently lowered to the ground, all while maintaining directional control. In a Champ, it’s both easy and desirable to do three-pointers. I can see where wheelies are useful, but I’ll need more practice before I’m comfortable with them.

I like full-stall, three-point landings because they seem more natural, coming as I do from a tricycle-gear environment where I want to get the nose up in the flare. My goal usually is that every landing results from a full stall right above the runway. Even in a slight crosswind, the Champ remains easily controllable down to the runway, into the flare and throughout the initial touchdown. As the airplane decelerates on the runway, keeping it straight also is relatively easy…until it isn’t.

There’s a brief period—especially on landing but also when taking off—when the Champ’s directional control might be considered up for grabs. A badly timed gust or poorly considered control input—or lack of input—at the wrong time can easily get the nose swinging around into the wind, with the tail dutifully following. If you don’t or can’t stop the weathervaning, the result usually is a ground loop and, if it’s done at sufficient speed, the airplane will drag a wing. Or worse.

Two More Differences

Most of the active control inputs necessary to keep the Champ on the straight and narrow on the ground are applied through the rudder and brake pedals. But taildragger pilots ignore the pitch control at their peril. With few exceptions, you’ll usually want the stick as far aft as it will go, placing as much weight as possible on the tailwheel to help keep it on the ground.

One of the exceptions can involve lightening the tailwheel by pitching forward on the stick (it’s almost always a stick) to help unlock it. Once it’s unlocked, and perhaps a burst of power is applied, the airplane basically can pivot around one main wheel. Cool thing to try when there’s plenty of open area around you—not so much on a crowded ramp. The other exception can come on takeoff.

I worked with two instructors in two different Champs to get where I felt comfortable soloing. One taught me to move the stick full forward/nose down at the start of the takeoff roll. According to this instructor, there’s no way the prop can touch the runway, and the idea is to relax that nose-down pitch input to neutral as the tail comes up. By the time the airplane is ready to fly, a slight back pressure is all that’s needed to lift off. Prop blast over the tail provides increasing rudder authority, so tailwheel steering isn’t necessary and getting the tailwheel light early minimizes drag during the takeoff roll. That’s important when going for maximum takeoff performance. But this is a Champ; there’s no such thing.

The other instructor wants the stick all the way back/nose-up when beginning the takeoff roll, to ensure the tailwheel provides steering authority as long as possible. As with the other method, the stick’s position is neutralized as the airplane accelerates and more air flows over the tail, until slight back pressure is all that’s needed to get some air under the wheels. Both methods work well as long as power is applied smoothly and is predicated on maintaining directional control, not acceleration.

The Champ is a simple airplane, and about as basic as flying can get. But because its little wheel isn’t where I’ve come to expect, I needed to develop different skills to handle it. Flying a taildragger can be a lot of work, but it’s also a lot of fun.

Jeb Burnside is this magazine’s editor-in-chief. He’s an airline transport pilot and owns a Beechcraft Debonair, plus half of an Aeronca 7CCM Champ.

I recently got my tailwheel endorsement in a Cub and have only a few hours in conventional gear airplanes. One of my instructors prefers what he calls a tail-low wheel landing, so not full-stall 3-point landing, but, he does them all. As I understand it, the wheel landing is helpful for gusty crosswind landings. If you try a full stall, you may have very little control authority if you get a bit of a gust. Wheel landings use a bit more air speed and flow over the control surfaces. On grass, the wheel landing is more forgiving. On pavement, when the wheels grab and prevent any side movement, a wheel landing in gusty conditions takes some more finesse. For me, I plan to get very comfortable with wheel landings so I can do them automatically if the conditions seem to warrant a wheel landing.

Like Mr. Burnside, I got my license before tail wheel endorsements were required. In fact, I did my flight test in a Cessna 140, the one in which I learned. That was years ago I owned a Cessna 172 for many years and most of my time is in that airplane. Would I jump into a Cessna 140 and fly today? Not on my life!! I would need a lot of refresher training. Tail wheel flying is indeed fun and challenging. In my opinion, it makes a more “respectful” pilot.