Like debates on high-wing versus low, discussions of “proper” crosswind techniques stand among those topics that split pilot opinions. Roughly speaking, it’s long seemed that aviators maintain membership in one of three groups: One group favors flying crabbed approaches and departures. Another insists the wing-low, upwind-gear-first technique works best. The final group recognizes values in both and offers an answer often irritating to members of the other two groups: It depends, they say. Pilots should be competent enough to embrace either solution to crosswind transitions, employing the technique best for the time, the place and the aircraft.

288

The debate even surfaces on aviation-oriented “reality television” programs. The pilots of ERA Alaska, in their best self-narrating style and as presented on episodes of Flying Wild Alaska, have told us why both approaches are ideal—or why they use one or the other—only to have another pilot conclude the exact opposite in the same episode. Even more fun is watching the approaches and departures with the multiple vantage points of the remotely mounted digital video cameras. From that video, a savvy pilot should conclude one thing—both techniques have their time and place. And the video frequently shows that pilots, in truth, tend to use a little of each technique on every crosswind transition. To the disciples of the two techniques, none deserve more space than those who wisely observe the debate with a solid grasp on the benefits and limitations of each, of the conditional variations in play and the necessity of yielding to aircraft types and then-and-there wind specifics.

Behind the Numbers

First up, let’s consider the mechanics of crosswinds, the limitations in play and how those limitations came to exist. We start by noting every certificated airplane earned its papers with a flight-test demonstrated number for the maximum 90-degree crosswind the airplane was shown to handle.

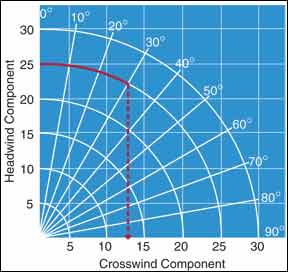

For most aircraft, that number is derived by regulation but isn’t regulatory in nature, coming either from Part 23 (for aircraft weighing no more than 12,500 pounds) or Part 25 (heavier than 12,500 pounds). For airplanes certificated since 1962, the Part 23 requirement is the maximum demonstrated crosswind component cannot be less than 20 percent of VSO—stall velocity, stuff out. That’s fairly low on most airplanes, since Part 23 sets the maximum stall speed for single-engine aircraft at 61 knots CAS. Twenty percent of 61 knots is only 12.2 knots. Part 25, certification transport-category airplanes—sets a minimum demonstrated-crosswind capability of 20 knots.

The maximum demonstrated crosswind capability is published in the pilot operating handbook (POH) or the aircraft flight manual (AFM), whichever applies. In most cases with most airplanes, it’s usually a safe bet crosswinds greater than demonstrated can be handled. For Part 23 drivers, that number simply informs us of the windspeed the manufacturer tested the plane to—which may be the most crosswind available when flying those sections of the flight-test regimen. And that number is unrelated to the engineering crosswind capability—a number with far more variables (landing gear, wing configuration, steering control, etc.). Regardless, the maximum demonstrated crosswind capability is a valuable number when briefing pre-flight. With it you should immediately recognize whether crosswinds require special consideration and, if truly excessive, a new decision for an airport. Even if reported winds exceed the DCC, it’s quite possible the airplane can handle more, which is legal under Part 91. But it’s only wise if the pilot doing the handling recognizes those limitations differences.

Finding Max Crosswind

The best method I use to learn those limits in any given airplane begins with seeking out a quiet, long runway offering the most crosswind possible on the day you choose to practice. Begin a landing approach—only the approach, please; we won’t be landing during the first few attempts—and start feeding in cross-control inputs until one of two things happens: you either run out of control authority or you overcome the crosswind. It makes no difference which technique you favor, crabbed or upwind-wing low. You’ll quickly recognize the difference.

288

Controls at the stops and still drifting? The wind exceeds your airplane’s actual crosswind capabilities. Controls almost to the stops and, crabbed or wing low, the airplane no longer drifts sideways across the runway? Check the reported winds, because that’s as close to your airplane’s maximum crosswind capability as you can get. Any more and drift resumes. So, record that speed and remember it. It’ll come in handy on many days in the future.

There are three other things to remember: First, the maximum actual crosswind number usually varies airplane-to-airplane within a model—typically due to small variations in the rigging of wings, tail and control surfaces. Second, the effect of torque and P-factor guarantees an airplane’s actual crosswind ability varies depending on whether the wind crosses from right or left. Third, low- and high-wing aircraft with the same demonstrated crosswind capability likely will have dramatically different maximum actual capabilities. That’s because crosswinds tend to be more effective at lifting upwind wings of high-wing planes than on low-wing versions with similar characteristics. The result? A Cherokee and Skyhawk of about the same weight, power and wing area will handle strong crosswinds quite differently.

Crab vs. Low-Wing on final: So…which crosswind technique do I favor? Count me among those who categorically believe the only answer to many of flying’s pressing questions is, “It depends.” It depends on the airplane, the day, the pilot, the airport…did we mention the pilot?

For me, that dependence hinges on what will work in a particular airplane at a particular time in the weather of the moment. In tricycle-gear airplanes, the wing-low approach method brings with it the benefits of a straighter landing, but one that can sideload the main gear, possibly to excess. Crabbing until the friction of all three tires on a runway straightens things out can adversely load the nosewheel. Both techniques necessarily call for higher-than-normal airspeeds on approach and delayed rotation on departure. These two methods are depicted and discussed in the sidebar on the previous page.

Some pilots employ the rule of thumb of adding one half the crosswind component to their normal approach and climb-out speeds. But several CFIs opined that the standard is too rigid—excessive for some crosswinds, insufficient for others. They all suggested using a memory aid highlighted in the sidebar on the opposite page.

Transition

Remember: At the end of a crabbed approach, the airplane must be aligned with the runway centerline before touching down. This means the pilot uses significant rudder input to straighten out the flight path before touchdown. So, during a crabbed landing, it’s important to hold the nose up as you gradually, gently transition from maintaining directional control with rudder to using the nosewheel.

For tailwheel airplanes, the wing-low final/one-wing-off-first take-off usually benefits the pilot with a more easily controlled transition, whether taking off or landing.

Remember, too, that the airplane will want to weathervane into the wind. The best technique is one that lets you maintain a track along the runway centerline as you climb—or on short final.

Time for a new decision?

Every pilot, like every airplane, has limits. Our personal limitations should be set in our mind before we drive to the airport. The FAA, safety authorities and instructors recommend, firmly, scratching a flight if the gust factor approaches 10 knots above the steady-state winds. In other words, a 10-knot crosswind, gusting to 20 is a lot of unpredictability to face.

Fifteen gusting to 25 would be worse, if for no other reason than the lower number usually will be bumping up against that maximum demonstrated crosswind component we discussed earlier. And consider scratching a crosswind takeoff anytime the angle off the runway centerline exceeds 45 degrees with a 10-knot gust—regardless of steady-state winds, numbers which should be obtained and assessed before leaving for the airport.

Further, no pilot should ever be surprised to find challenging crosswind conditions prevailing at any airport—departure or destination. At the departure airport, you can watch the windsocks, how other pilots fare on landings and takeoffs. Learning the observations at the destination might not be as simple, but there’s always the solution of picking up a telephone and calling. If the airport doesn’t report its winds, be sure to consult the area forecast and nearby facilities with Metar reporting to learn what you might be getting into.

Then update your information when you get near enough to the airport to hear pattern traffic, listen to the local ATIS, AWOS or ASOS, and watch the wind indicators as you pass the airport.

Obstructions

Ever watch a windsock on a particularly windy day and marvel at how it occasionally seems to pirouette about its hinge pin? Maybe even point narrow-end up? Now, close your eyes for a moment and try to imagine the air movements prompting such windsock gyrations. These sorts of atmospheric antics often result from the spillover of air downwind of objects bordering runways.

When wind blows against tree lines, fences, buildings and terrain features, among other things, turbulence and unpredictability are the rule. Flying through strong, disturbed air can prompt sudden altitude loses and gains—which generally are not happy happenstances when close to the ground. Pilots based at airports with these issues usually know them well and fly accordingly—or, don’t fly, accordingly.

Rotors can be an approach or departure issue when strong winds align with the runway, or anytime the object or terrain feature sits not far enough beyond the runway threshold.

Now, with these pictures of atmospheric chaos in mind consider: Why would you want to risk limb, wing or life tackling such unpredictable conditions? Unless it’s a life-saving mission, chances are the flight can wait.

Know when to say No

Crosswinds are not something that magically appears one day, forcing you to cope. You likely were introduced to them gradually and the foregoing should help you decide how and whether to handle them when they’re pushing at or beyond capabilities. Variables to consider include the airplane and its characteristics, your skills and comfort level, the airport environment and the mission.

Sometimes the only smart decision is the hardest one to make—the no-go decision. You just say “No,” decisively, quietly and move on to the next plan.

Dave Higdon is a Wichita-based aviation addict who writes about and photographs aviation subjects to fund a flying habit picked up during the Disco Era.