So I’m flying along one day, fat, dumb and happy in the pattern at the Winchester (Va.) Regional Airport, KOKV. When I lived in the area not too long ago, Winchester was our preferred local practice field when Leesburg Executive Airport (KJYO), my airplane’s home base, got too sporty.

There were many other area airports a pilot could go to, like Martinsburg (Eastern WV Regional Airport/Shepherd Field, or KMRB). Martinsburg was cool because sometimes a C-17 would be flying (a very wide traffic pattern) or doing some kind of cockeyed low-level combat approach. The main drawback of mixing it up with the C-17s at KMRB was the wake turbulence: It could fling you like Dorothy and Toto to the Land of Oz.

We could also go over to the Frederick (Md.) Municipal Airport, home of AOPA and the snippiest tower controllers in the Lower 48. Or we could go fly down the Shenandoah Valley to Front Royal and do touch-and-goes on their 3000-foot-long, 75-foot-wide strip with a mountain at one end and trees off either side.

So Winchester was our favorite, plus it had 5000 feet of concrete.

Oh, Deer

Back then, on the Interwebs, I came across something resembling this: “A pilot was attempting a touch-and-go landing at night in a Cirrus SR20 at the Winchester Regional Airport. Just as he was rotating, he saw a deer run across the runway and heard a loud bang as the airplane veered slightly to the left. The pilot thought he had hit a deer, and….” The story went on to talk about how it turns out it was a deer, after all, and really damaged the wing. The pilot found out about the wing damage when he came in to land, and the wing dropped and hit the ground, which, it turned out, damaged the wing even more. The “lesson,” the article said, was to “watch out for deer when doing touch and goes near wooded areas.” Ya don’t say.

A quick search of KOKV’s deer-strike history, using the FAA’s wildlife-strike database, at wildlife.faa.gov/search, shows there were five deer strikes since 2003 at KOKV, two of which were in one unlucky five-day stretch during March 2003. All reports said the aircraft damage was substantial. The deer were not available for comment.

It’s legal, according to the FAA, to do touch and goes at night at KOKV or near dusk. But maybe in the spirit of the managing risk, flying at Winchester near dark or in the dark is dicey? On account of deer strikes?

Or, we could be proactive—defensive, if you will—during night operations at KOKV by making a low pass down the runway with our landing lights on, to look for deer and other critters. This is a tried and true practice at many airports (see the sidebar on page 6) during both day and night operations.

It was November 17, 2012, just before noon, at the Greenwood County (S.C.) Airport (KGRD). A Cessna 550 Citation II registered to the U.S. Customs Service was touching down on Runway 09. According to the NTSB, “About 5 seconds into the landing rollout, a deer appeared from the wood line and ran into the path of the airplane. The deer struck the airplane at the leading edge of the left wing above the left main landing gear, and ruptured an adjacent fuel cell.” The pilot flying kept it on the runway and came to a stop, with the airplane spilling fuel and on fire. The two ATP-certificated pilots egressed and were not injured. The already-damaged airplane was mostly consumed in the post-crash fire. The flight was a post-maintenance test hop conducted after cockpit modernization.

An interesting thing about this accident was the airport’s wildlife control program. According to the NTSB, the airport manager had been proactively working to minimize the risk of wildlife hazards, primarily deer and wild turkey. One action taken was to approve tightly managed depredation permits to take deer on the airport property, which came to average 50 deer per year. After this accident, the FAA funded a 10-foot outer perimeter fence. Since the new fence went in, only four deer have been taken inside the perimeter and no wild turkeys have been sighted. — J.B.

Patterns Of Behavior

Speaking of attacks, KOKV has no tower. It’s “uncontrolled,” as some people call non-towered airports. In fact, non-towered airports are subject to long-standing rules and recommendations on how to enter, use and depart traffic patterns.

Instead, pilots enter the KOKV pattern every which way, and exit the same way, which is “every which.” The fact is the pattern behavior at KOKV isn’t all that different from other non-towered airports in the U.S, though perhaps not in other countries.

I once heard a fellow flight instructor on the radio transmitting, “Skyhawk 3247Y, exiting Runway 32 pattern to the northeast.” Excuse me? A right turn out of the traffic pattern? That same guy was furious at some pilot who was entering the pattern on the Runway 32 crosswind one day, and they went head-to-head, both too stubborn to turn, experiencing a little air rage.

My pilot/CFI buddy said, “The guy was coming right at us!” I thought, “A thousand-plus hours, gonna be an airline pilot soon, and you’re exiting the pattern with a right turn to save a few miles—to save a few minutes—because it’s a shorter distance back to Leesburg?”

Yup, that was his decision-making process.

Was what either pilot was doing wrong? Not really, not technically.

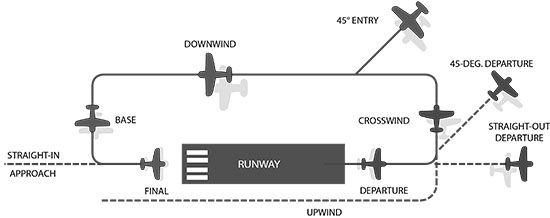

Aren’t you supposed to exit the pattern straight out or with 45-degree left turn? (No, not with a “last call” radio call! Bad dog!) Aren’t you supposed to enter the pattern on the downwind at pattern altitude, or maybe do a straight-in? Why, yes, you (and me) are. But it’s not illegal to do whatever they were doing, the FAA says, as long as you make left turns for a left pattern and right ones for a right pattern.

Not A Lawless Frontier

Those are recommendations, found in FAA’s guidance, like the Aeronautical Information Manual (AIM) and the complementary Advisory Circular AC 90-66C, Non-Towered Airport Flight Operations. Right up front, the AC points out there are rules at these airports.

For example, there’s FAR 1.1, which defines “traffic pattern” as “the traffic flow that is prescribed for aircraft landing at, taxiing on, or taking off from, an airport.” There’s FAR 91.113 (Right-of-Way Rules: Except Water Operations), and FAR 91.126 (Operating On or In the Vicinity of an Airport in Class G Airspace). And if you thought these regs have no teeth to them, the AC also references FAR 91.13 (Careless or Reckless Operation).

So there’s the letter of the law and the spirit of the law. If I do a straight-in, and there’s an aircraft or three in the pattern, who’s going to give way on final? Is it the guy on base—maybe he’ll break out so he doesn’t hit me—or should I break off my straight-in for him? Maybe the person on downwind can extend, and then turn onto the base leg and tuck in behind me? What does the AIM say?

“Pilots are encouraged to use the standard traffic pattern. However, those pilots who choose to execute a straight-in approach, maneuvering for and execution of the approach should not disrupt the flow of arriving and departing traffic. Likewise, pilots operating in the traffic pattern should be alert at all times for aircraft executing straight-in approaches.”

In other words, everyone should use the pattern designated for that runway, except when you want to land out of the straight-in instrument approach procedure. In honest IMC, it’s unlikely but not impossible that someone else is stumbling around in the clag, and you could break out on a one-mile final only to see bogies swarming like fireflies. In good VFR at a busy non-towered airport, the only reason to fly a straight-in is if you’re on fire. Do the smart thing and join the pattern on the 45 to the downwind, and then fly it to touchdown.

Most guidance on landing at rural or remote airports includes ensuring that the runway surface is clear of obstacles. The most common way to do that is to perform a low pass, something at which few pilots have much practice. The good news is it’s like a touch-and-go but without the touch. The bad news is we screw those up, too. And within that realization are the keys to doing this successfully. May we suggest:

Fly the pattern designated for that runway, configuring the airplane as you normally would for a landing, except maybe not deploying full flaps. Half flaps gives you additional lift at approach speed while minimizing drag, and can make the go-around portion of the low pass easier to manage.

When you would normally reduce power and begin to flare for a landing, don’t. Pitch for level flight and add enough power to maintain your final approach speed.

Don’t descend to the runway, but fly 20 to 50 feet or so above it, scanning for obstacles, mobile and immobile. Enlist your passengers’ assistance.

Initiate your go-around no later than the end of the runway by adding full power and beginning a normal departure climb. One difference likely will be when a normal takeoff doesn’t call for partial flaps, so be ready for the hefty pitch up as you add power.

Drag reduction is your next task, which can include gear (quickly) and flap (do it in stages) retraction.

Climb to pattern altitude, turn onto the downwind and repeat, landing this time out of the approach.

Or not. If you saw something, you have two choices: perform another low pass for verification or go somewhere else. — J.B.

What Does It All Mean?

It’s easy to get complacent at the typical non-towered airport, where operations are infrequent and transients few. The facility likely is not attended except during the workday, and we might think we’re the only ones out on this fine evening. Right up until Bambi sprints out at us from the treeline. Truth be told, even a low pass or two may not help, since deer aren’t that smart and don’t understand whirling propellers. Even if you’ve boned up on the Notams and read the Chart Supplement entry, there are no guarantees.

The same complacency can creep in when, for the last 20 minutes as you descend, there is not a peep on the CTAF, only to find a Nordo Cub is shooting landings or another airplane announces a takeoff from the opposite end of the runway we’re approaching. Probably not a good time to be aiming for the straight-in, even if it is oh so tempting.

One of the often-forgotten reasons we’re encouraged to fly a full pattern is the opportunity it gives us to scope out the airport environment and the landing area. As we’re looking around the pattern for traffic, we also should be scanning for obstructions on the runway. And perhaps more so than at a towered airport, we always should be primed to go around, for whatever reasons. It’s Defensive Flying 101.

Matt Johnson is a former U.S. Air Force T-38 instructor pilot and KC-135Q copilot. He’s now a Minnesota-based flight instructor.