It’s happened to me three times. The first time happened about a year after I earned my Private Pilot certificate. About a week before my Practical Test I accepted delivery of NC89954, a 1946 Cessna 120. The 120 is a side-by-side two-seat tailwheel airplane with fabric-covered wings and an 85 horsepower engine. It’s the airplane that eventually evolved into the Cessna 150 and 152.

With about a year’s experience in type, I launched on my first epic aerial journey, from my home in central Missouri to Detroit to visit family. My dad, a Honolulu-based airline mechanic and one-time lightplane pilot himself, flew in to Kansas City to join me on this odyssey. Our first leg stopped in Hannibal, Missouri, just short of the Missouri River.

The second leg was from there to a fuel stop at Pontiac, Illinois. Touching down, I taxied to the line shack in that day before self-serve fuel pumps. The building was locked. I used the adjacent phone booth to call the after-hours service number even though it was about one o’clock on a weekday afternoon. No one answered.

The second time I was flying a Beech Sierra. My wife and young son had flown the airlines from eastern Tennessee where we lived at the time to visit my in-laws in western Missouri a week before, and I was flying up at the end of their trip to bring them home. Landing in extreme west Tennessee—a very long state—for fuel, I found the self-serve pump’s credit card reader wasn’t working. The kid working the line had no better luck than did I, and none of the cards I was carrying worked. There was no way for me to get fuel.

The third time (I won’t say last, because I’m not done flying yet) I flew a Beech Baron from near Chattanooga, Tennessee, about an hour to Nashville to pick up a passenger at a large FBO on the commercial airport, KBNA. From there, we would fly about an hour and a half to the passenger’s first stop of a long travel day. It was extremely cold and I had a very early show time at Nashville, so instead of topping off the tanks before leaving my home airport, I chose to leave early enough to have time to fill up while waiting for my passenger at Nashville. Arriving at the only FBO at BNA selling 100LL in those days, I learned that their fuel truck wouldn’t start in the cold and I could not get gas.

BEST-LAID PLANS

What happened in each of these cases was that I landed at a planned fuel stop only to find fuel was not available. None had a “100LL not available” Notam to warn me. This sounds like the set-up to a decision that culminates in an NTSB report. Happily for me, and for those flying with me, this was not the case.

With my dad in the Cessna 120, I dipped the tanks at Pontiac and confirmed I had more than enough gas to fly 15 miles up the interstate to Dwight, Illinois, where we topped it off. Flying the Sierra, I made sure I had plenty in the tanks to make a short hop across the Kentucky border to another airport and land with a healthy 45-minute reserve when I would arrive. In the Baron, I checked multiple fuel level indicators—the fuel gauges, a fuel totalizer, float-type sight gauges on the top of each wing and my written record of tach time since fuel last added—and since they all agreed, determined I could make the next stop with over an hour still in the tanks upon landing.

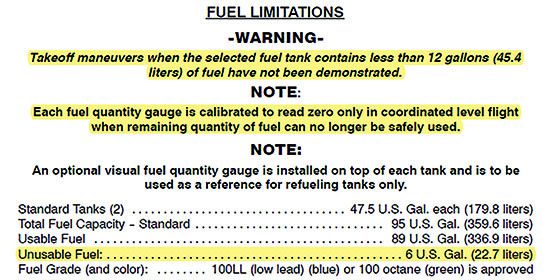

Depending on what you fly and when it it was certificated, the unusable fuel aboard your airplane could be completely different from the one parked beside it on the ramp. The graphic above, from the POH/AFM for Mooney’s M20R Ovation 2 GX, shows the various fuel-related limitations associated with the type, including total capacity, grade and the unusable amount. Since the M20 series was originally certificated under the old CAR 3 rules, and applicable portions of FAR 23 it predates, it’s unclear if the newer requirements apply. If they do, the relevant regulation is FAR 23.959, which states:

The unusable fuel supply for each tank must be established as not less than that quantity at which the first evidence of malfunctioning occurs under the most adverse fuel feed condition occurring under each intended operation and flight maneuver involving that tank.

That’s a somewhat vague requirement, but it does make an airframe manufacture test to determine under what circumstances the flow of fuel from a tank may be interrupted during expected flight maneuvers. If you’re flying something bigger, FAR 25, certification of transport category airplanes, may apply. In that case, FAR 25.959 applies, and makes it a little clearer what the FAA is looking for in the way of determining unusable fuel:

The unusable fuel quantity for each fuel tank and its fuel system components must be established at not less than the quantity at which the first evidence of engine malfunction occurs under the most adverse fuel feed condition for all intended operations and flight maneuvers involving fuel feeding from that tank. Fuel system component failures need not be considered.

STRETCHING THINGS

Based on what I see in various online forums, there seems to be a vocal percentage of the pilot population who take pride in flying maximum-range trips, landing with minimum fuel on board. Often this is combined with stops where fuel prices are lowest, which usually means self-serve fuel pumps at airports with minimal services. This percentage may be growing; it may be more or less constant and we’re just hearing about it more often.

I’m all in favor of saving money, but lowest-fuel-price airports are often locations with little to no help available if something goes wrong with the fueling system. This can put a pilot in a bind, on the ground without enough fuel to fly to even a nearby airport with adequate reserves. In some airplanes, they might be unable to take off within the type’s legal limitations for fuel on board. Put yourself in a similar bind and you’d be very tempted to take off, but with a much greater likelihood of experiencing fuel starvation or exhaustion.

USABLE FUEL

Talk to a group of pilots about distance flying and the conversation will inevitably turn to the concept of usable fuel. More correctly, someone is likely to bring up the idea that unusable fuel is a legal dodge by the airframe manufacturer and that he (or she) can burn more out a fuel tank than the placarded usable fuel amount. In reality, manufacturers must test airplanes for unusable fuel, and if an unusable fuel quantity is published or placarded for your aircraft, it’s the result of actual testing. The sidebar on page 17 details the FAA’s unusable fuel certification rules for small airplanes (FAR 23) and large ones (FAR 25).

For example, the Beech A36 Bonanza I most often fly is placarded as having three unusable gallons of fuel in each main tank: In fact, YouTube personality Scott “Gunny” Perdue notes in an episode of his Flywire channel that he found his Bonanza would unport with as much as about seven gallons in a tank even in a normal, en route descent attitude with good rudder coordination.

In general, you may be able to burn unusable fuel under some circumstances, in smooth air while in straight-and-level flight. If you can access that fuel and feel the extra few miles it will carry you makes the difference between whether you’ll arrive safely at your destination, well, that’s up to you.

A July 22, 2022, accident near San Jose, California, substantially damaged a Piper PA-32-301 Saratoga when it lost all engine power in initial climb and impacted terrain, seriously injuring the solo pilot.

This accident occurred near Reid-Hillview Airport (KRHV) in California, an airport that had banned the sale of 100LL aviation gasoline. The AOPA is suing the airport authority to force it to resume selling 100LL. According to a brief in the lawsuit, the Saratoga pilot arrived KRHV with about 30 gallons of fuel aboard. On departure, after receiving unspecified maintenance, the airplane had “little to no fuel remaining” and its pilot attempted to fly six miles to obtain 100LL.

The pilot made a conscious decision to take off with a known low fuel state. It goes against decades of aviation safety advocates’ emphasis on good fuel planning and management practices and pilot-in-command responsibility. There may be legitimate reasons to compel the airport to resume 100LL sales, but this is not one of them.

COMING HOME

For a time I was the safety officer in a large flying club with a dozen airplanes and about 300 members. The club was sponsored by an aircraft manufacturer at its factory airfield. An unusual feature of the club was that fuel was provided free by the manufacturer—if you waited until you made it back the avgas was free but if you bought fuel away from home, it was on you. There was a strong financial incentive to stretch fuel.

As non-employee, I was invited into the club after a couple of mishaps not related to fuel management caused the manufacturer to “suggest” the club get an outsider with safety credentials to take a close look at the safety culture. I told them the fuel policy, although very favorable to club members, was a fuel starvation or exhaustion accident waiting to happen.

Sure enough, soon afterward one of the club airplanes returned from a trip with about 10 minutes of fuel remaining. No way was I going to suggest ending the free fuel policy, but I did recommend strictly enforcing a minimum fuel rule with suspension from flying privileges and a retraining requirement. Not many of us have a generous benefactor paying for our avgas, but we still may have strong incentives to seek out the cheapest fuel.

DECISIONS, DECISIONS

It’s tempting to shorten door-to-door trip time by flying maximum-endurance flights without a fuel stop. When making a longer trip, many pilots fly the longest legs they can. Often we’ll go out of our way to find the cheapest gas; we often have an incentive to get back home with the greatest amount of air in our tanks because the avgas is less expensive for us there. Any of these practices can set you up for a fuel-starvation or fuel-exhaustion accident.

Instead, leave yourself options: Land with enough gas aboard to go get more if you reach a planned fuel stop only to find there’s none available. Choose where to fuel based on price if you like, using the fuel price feature on most tablet-based flight planning software or on web-based flight planning services. Decide whether and how much fuel to add based on actual requirements with a very healthy reserve. Resist the temptation to stretch your fuel until you’re somewhere where the fuel price is low.

Tom Turner is a CFII-MEI who frequently writes and lectures on aviation safety.