Everything seemed routine. My clearance included direct to the destination at a safe altitude for the high terrain along the route. Taxi and runup went smoothly. But before I switched to the tower frequency, ground called to say, “I have an amendment to your altitude.” Turns out the new altitude was too low for the terrain along the direct route in the clearance.

“Um, sorry, we can’t accept that altitude on that route.”

“Let me check,” the controller replied. A few minutes later he came back with an apology and a new clearance that started us along a Victor airway whose MEA was well below the revised altitude I’d been assigned. Someone at ATC made a mistake.

ATC’S ROLE

Air traffic control’s main purpose is to keep aircraft from hitting things. Missing other aircraft is the higher priority; missing the ground is the next. To do this they need the “big picture,” which is sometimes difficult for pilots to find. I explain it to students this way: “We tell them what we want to do, and they tell us why we can’t do it.” That might involve something we can’t possibly know about. It can be a very complicated situation, with more factors than most people can keep in mind. That most controllers can keep it all in mind makes them special.

The system is basically 100 percent reliable. Basically. Which means not always. In the scenario above, there was another airplane flying along the direct route, and the lower altitude in the first revised clearance kept us apart. The problem was that it wouldn’t keep me out of the weeds. It took a new route to do that, but somehow that information didn’t get passed along. Until I asked.

With that firmly in mind, the rest of this article can be summed up in two principles: First, listen—really listen—to what ATC is asking you to do. Second, if something is scary, or even just confusing, ask for clarification. That’s it. But it’s fun and informative to look at the overall situation in more detail.

LISTENING

Listening is an active process, and anyone who’s been married, in a relationship, had a co-worker or tried to buy a cup of coffee—each of us, in other words—should know it is both important and difficult. Sometimes listening means noticing what’s not there. This doesn’t need to be a mistake. For example, a holding clearance with no direction of turn means right turns. No need to say it. When a controller vectors you off a standard arrival route, one outcome is the arrival clearance is canceled. Again, no need to say it. Pilots are supposed to know this stuff.

Another example of the two-way nature of listening is something I overheard on a center frequency. A business jet approaching a mountain airport was cleared to a lower altitude, one ridiculously high for approaches in the flatter parts of the world. The jet read back the clearance with a lower altitude, probably something closer to the usual intermediate altitudes they flew. Except here, the readback altitude was underground. The controller didn’t catch the error immediately. A few minutes later they called in a panicky voice saying, “Low altitude alert [callsign], check your altitude immediately.” Luckily the weather was VMC.

This was two errors, one by the crew, one by ATC. Neither listened, so neither queried. Errors often come in pairs.

A bizarre example of not listening involved callsigns. For a while, my company and the National Guard in a nearby state used the same callsign prefix. One day, I was very surprised to hear an ANG aircraft check in with the exact same callsign I was using. The controller hadn’t noticed.

Listen, and query. “Center, you’ve got two aircraft with the same callsign on the frequency. I’m going to change mine to “civil [redacted], and suggest the other use military [redacted].” Everyone agreed to this.

The words and phrases ATC uses can seem like a language all its own. Thankfully, there’s a dictionary or phrasebook for this formal language: the FAA’s “Pilot-Controller Glossary,” the agency’s online version of which is appended to the aeronautical information manual, or AIM. It spells out exactly what controllers mean and expect when they do (or do not) use a phrase. The problem is that it’s huge and, like a phrasebook for a foreign language, includes a lot of phrases you are unlikely to use.

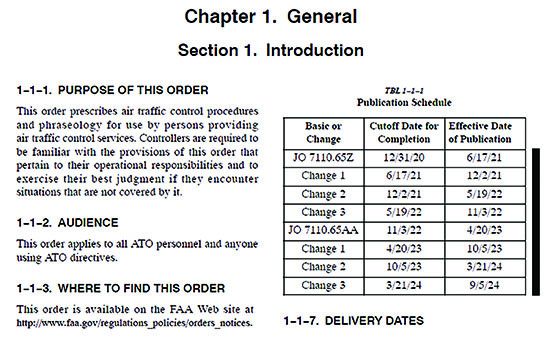

Another resource is FAA Order 7110.65Z, “Air Traffic Control,” widely considered the controller’s “bible.” In addition to clearance examples, it presents all the big-picture rules and procedures controllers are to follow. Like the P/CG, it’s thick. It also is huge, and detailed. It also can be boring—if you have trouble sleeping, try reading this. It probably makes more sense in the context of actual use.

Of course, the AIM itself is a must-have resource for anyone looking for additional detail on how ATC and pilots work together, and how they support the national airspace system.

HANDOFFS

A lot of the problems I’ve witnessed have involved handoffs, both VFR and IFR. These are not necessarily errors but are the kind of thing that might lead to errors.

One would think that this kind of problem would happen more at lower altitudes where aircraft might fly out of transmitter range, but spend some time listening to the Guard frequency, 121.5. MHz. You’ll hear dozens of calls to airliners that go something like, “If you hear this, contact Albuquerque Center on [frequency].” And you’ll hear dozens of calls from airliners asking something like, “Who should we be talking to now?” When the radios go quiet, listen harder.

Usually these problems have easy solutions. On a bluebird day, I had a few minutes to relax as I cruised toward Oregon at FL220. That’s easy flying. The air was smooth, there’s almost no need to scan for traffic in Class A airspace, I still had over an hour to go, and the scenery wasn’t bad, either. Nothing to do but monitor the engines and pressurization and the radios.

The radios were quiet.

My moving map indicated that I had crossed into Seattle Center’s airspace.

The radios were quiet.

I checked the radio volume. It was not turned down. I made sure my second radio was listening on Guard.

I’m not sure what made me decide that enough was enough and finally call Seattle Center. “We’ve been waiting to hear from you,” a friendly voice said. “You’re right where you’re supposed to be.” Somewhere along the way, the previous sector never completed my handoff to Seattle.

TRAINING

One of the real-world complications ATC faces is the need to train new controllers. That goes about as well as training new pilots. Both new pilots and new controllers make mistakes.

There’s more to that than meets the eye. Someone new to an ATC facility has to learn all the fixes and approaches. Most pilots can imagine what goes into that. But there are local procedures to learn as well. There may be letters of agreement (LOAs) with adjoining facilities that state clearly what each facility’s responsibilities are. Pilots don’t always need to know these, but controllers do.

There are other local procedures that many pilots may not think about. What happens when the fire department does their runway sweep? What are the protocols for maintenance personnel to cross active runways or enter the movement areas?

And there is the art of sequencing aircraft. The airport I fly from now has no airline traffic but there are several aeromedical helicopters, a flock of corporate jets and a lot of flight training. There’s also some terrain and a noise-sensitive area to contend with. It’s a lot for someone to master, and at least one former controller there never really did.

The jets want and need a stable approach, which means a longer final, so some of the traffic on downwind is going to have to extend. That’s the controller’s job. But in the meantime, there might be a helicopter approaching perpendicular to the traffic flow. Can the helicopter fly a lower pattern straight to the ramp without crossing the active runway? I don’t know. Controllers do.

Controllers can only learn this from experience. With this level of complexity, there are bound to be mistakes. Generally the trainers jump in to fix them, but something might interfere. Listen, and if something doesn’t sound right, ask.

It can be difficult to get into a controller’s head. One way is to spend some time with an ATC simulator game, but without guidance it can leave you repeating the same mistakes. Another is to listen to internet feeds of ATC communications, like LiveATC.net. It helps to have relevant charts handy and watch a flight tracker like FlightAware to help you form the big picture.

A better option is the “Opposing Bases” podcast. It features two Tracon controllers who are also pilots. They share a lot of insights into how they think about ATC’s role. It’s almost like being able to sit next to them in the radar room or tower as they explain the why and the what.

There are a lot of things involved in ATC that we as pilots aren’t exposed to, like letters of agreement (LOAs) between adjacent facilities and various other standard operating procedures (SOPs), which may or may not be standard. The LOAs and other informal procedures can help reduce ATC workload, but also can be a pain for pilots, especially when we’re off the beaten path and expecting something different.

SATURATION

Most of the time, ATC can accommodate all but the strangest requests. Sometimes they can’t, usually when their sector is saturated with everyone wanting to be aloft at the same time, so you might hear something like, “Remain clear of the Class D airspace.” Can they do that?

Yup: AIM paragraph 3-25 (b)(2) states, “If workload or traffic conditions prevent immediate entry into Class D airspace, the controller will inform the pilot to remain outside the Class D airspace until conditions permit entry.” In every case I have heard this, the tower controller has been super busy, and there just wasn’t enough room on the frequency to communicate with that many aircraft.

Of course, workload is in the eye of the beholder, and the rules give the controller the option of deciding when he or she is too busy to accept another aircraft. The same option exists when operating VFR and wanting Class B entry, or elsewhere when simply seeking flight-following services. If ATC doesn’t respond, the answer is ‘no.’”

LOST COMMS, AGAIN

Of course, ATC is a lot more than controllers. There are lots of machines—transmitters, receivers, repeaters, radar antennas…the microwave channels that get data from the far reaches of a center’s airspace to the radar room itself. A broken machine is, in a sense, an error, just not a human one. The most common ones are radar outages and transmitter failures.

When maintenance is being performed, that radar is unavailable, so controllers and pilots have to know how to handle it. Another aircraft’s emergency can mean lost communications for you if the controller is too busy working the problem to work you.

If you are familiar with the area you can hand yourself off to the usual next frequency. If not, you’ll have to figure out a new frequency. If you’re inbound to an airport with a tower, I would try the tower frequency first, bypassing approach control. If you’re departing, try going straight to the en route frequency.

The rules regulating basic flight operations, often just referred to as FAR Part 91, can be a never-ending source of confusion for IFR pilots. One of the most confusing is FAR 91.185, “IFR operations: Two-way Radio Communications Failure.” It’s all about what to “expect.” That’s the magic word ATC uses to tell you their plan. Perhaps the easiest example is that the altitude ATC has told you to “expect” is one of the factors in deciding how low you can fly (Hint: Fly at the highest of the available choices).

A more difficult example might be the route. The “expected” route is one of the things you have to choose between. One common place to see this is when ATC clears you to an initial approach fix (IAF), followed with an “expected” approach, as in “Cleared direct EXRAY, expect the ILS Runway 36 approach.” If you lose radio communications, you now have a route to follow.

The hardest example is the “expect further clearance” time, because ATC doesn’t have to provide one. The FARs tell you what to do if you don’t have one.

CLARIFY

Although we all should periodically study the Pilot-Controller Glossary, the AIM and the Air Traffic Control order (see the sidebar on page 9), it’s usually not possible for a mere pilot to understand everything in that guidance. The good news is AIM paragraph 5-5 has a recurring theme: If something doesn’t sound right, it is the pilot’s responsibility to ask. According to the AIM, pilots in doubt should request “clarification or amendment, as appropriate, any time a clearance is not fully understood or considered unacceptable from a safety standpoint” and should question “any assigned heading or altitude believed to be incorrect.” In other words, ATC expects you to ask if something sounds wrong, scary or confusing. Failing to ask is a pilot error.

SHORT FINAL

Yes, ATC is nearly 100-percent reliable, but that still leaves a gap, so pilots are expected to listen to what they tell us and to speak up if something doesn’t feel or look or taste right. Listen, and query. The certificate you save may be your own.

Jim Wolper is an airline transport pilot and retired mathematics professor. He’s also a CFI with single-engine, multi-engine, instrument and glider ratings.