Everyone talks about the weather but no one ever does anything about it.” (Stop me if you’ve heard that before.) The same could be said about managing the risk of general aviation. We—both this magazine and the industry as a whole—spend a lot of time preaching to pilots about the mechanics of understanding weather forecasts, determining if the aircraft is capable, and making honest evaluations of our own performance in considering how and when to conduct a flight. But once we identify the need to mitigate a risk, we sometimes have little space left over to describe the tools we can use. Let’s try to fix that.

The typical GA pilot is exposed to three broad risks: weather, aircraft suitability and pilot capability. When the proposed flight raises complications in these three basic areas, we should consider what we can do to bring the increased risk down to acceptable levels while still accomplishing the mission.

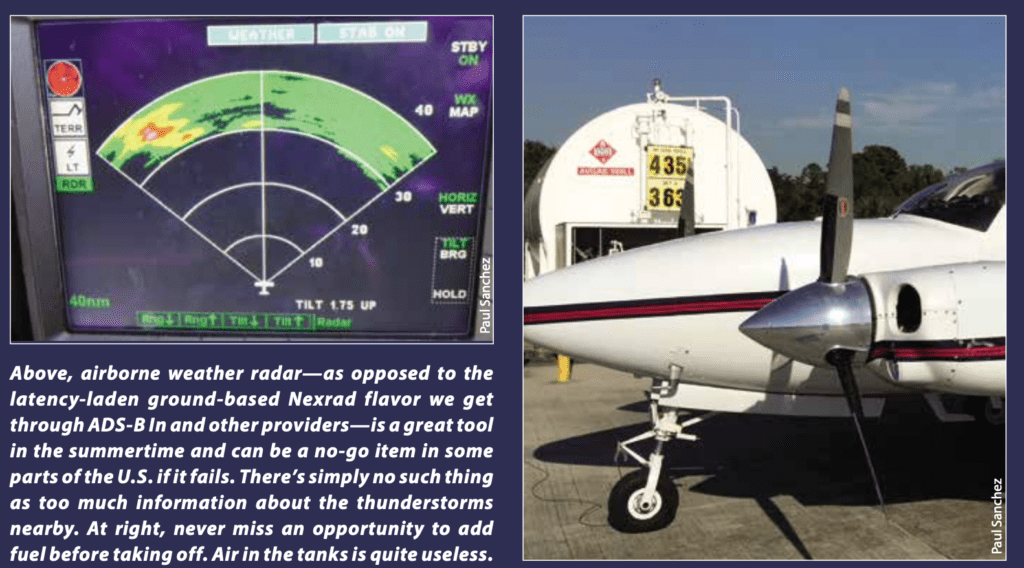

WEATHER

To me, weather is the factor posing the greatest risk to safely and reliably operating a personal aircraft. To properly manage this risk, we first have to understand it, and then evaluate the options we have. Weather is a “what you see is what you get” kind of thing—you can’t change it, but you usually can work your way around the worst.

1. A thorough preflight briefing.

There really is no excuse for not obtaining a thorough preflight weather briefing of some sort. You can call Flight Service on the way to the airport. You can pull up anything you want on your phone before takeoff. The tablet you use in flight probably has the capability to download a complete briefing, including graphics, and organize the results for you.

Of course, what we need on a severe-clear daytime flight in search of a familiar $100 hamburger will be a lot less than a wintertime night flight near the Great Lakes. So it shouldn’t come as a surprise that a preflight briefing’s detail level should be based on the briefing itself. That said, details about airports, available approaches and how the weather may impact operations are always important.

2. Timing is everything.

Another popular saying about weather is something along the lines of, “If you don’t like this weather, just wait a bit and it will change.” This truism would seem to have been tailor-made for aviation since that’s pretty much exactly what happens: If you wait long enough, weather will improve.

Often the weather is moving and—since you can’t do anything to change its trajectory—the smart thing to do is let it. If there’s a cold front approaching your departure airport, stay on the ground. It’ll soon pass overhead and you can launch into clearing conditions.

Afternoon thunderstorms and early-morning fog all move and evolve, but perhaps not on our desired schedule. Tough—change your schedule. Leave a day ahead, or later in the day. The point is to remain flexible in your scheduling to allow for poor weather. Plan things so you can wait a couple of hours without impacting your mission.

3. Go around the problem.

Some weather conditions don’t move quickly, or they occupy a wide area. The low ceilings and visibility sometimes associated with a warm front come to mind, as does the wintertime inflight icing risk. But you have an airplane. Use it to fly around the problem areas.

This plan of action doesn’t work well, of course, if your departure or destination airports are socked in or covered with ice-laden clouds. But those conditions will change, eventually. Sometimes it’s worthwhile to get as close as you can to the weather problem and go the rest of the way the next morning.

I’ve often told a tale about a planned trip to Key West in the winter that didn’t happen due to widespread IFR conditions. I didn’t have an instrument rating at the time, but I also didn’t think about it long enough to realize I could have gone around the conditions by abandoning a direct route. I would have had to stop for fuel anyway, but I was so focused on flying direct that it never occurred to me at the time I could go around the problem.

4. Change your altitude

A lot of weather problems can vary with altitude. Icing above 12,000 feet usually isn’t an issue at, say, 8000, presuming terrain allows cruising that low. If it doesn’t, find a route around the icing at an altitude that resolves both the icing and terrain issues. If you can’t find one, wait.

A lot of weather and related risks can be mitigated by changing altitude. If there’s a deck of clouds you don’t want to fly in, there’s likely an altitude that will keep you out of it. By the same token, the jaunt across Lake Michigan to get to Oshkosh from the east coast is a lot less risky at 10,000 feet than it is at 4000. Headwinds often can be at least partially mitigated by changing altitude, presuming terrain allows. In the same vein, turbulence generated by air moving over that same terrain can be minimized by climbing and perhaps accepting the headwind.

AIRCRAFT

The old drag-racing sentiment—there’s no replacement for displacement—also rings true in personal aviation. I’m a strong advocate of using as much airplane for the task as you can afford. As I’ve written (and been chastised for) in the past, my personal minimum for a traveling airplane on “real” cross-countries is 180 hp. In some areas of the U.S. and elsewhere, you can “get by” with less, but you also give up some flexibility and capability. And it takes too darn long. If the airplane isn’t right for the mission, wishing and hoping it’ll be okay won’t make it better.

But there’s more to choosing the weapons with which we do battle against the elements than just horsepower. What about avionics? Is the airplane’s installed equipment up to the proposed task? You’re not trying to make up for its equipment shortcomings by using portable devices, are you? Got current databases, right? Beyond avionics, what about filled TKS fluid tanks, or supplemental oxygen for climbing high and survival gear for the terrain and season? What about loading—will your at-gross 145-hp Skyhawk crap out at 8000 feet in the summertime with all its seats filled? (Hint: Probably.)

5. You can never have too much fuel.

Just as with getting a preflight briefing, I’ve always been one to maintain that there’s simply no excuse for running out of fuel. Yes; headwinds happen, and FBOs sometimes close at inconvenient times. Deal with it. Ensuring there’s adequate fuel is one of the responsibilities you accepted when you went for your private checkride. That responsibility doesn’t change when you overfly the last fuel stop before your destination because it will take too long.

You have a number of options: Land short of your destination if headwinds are stronger than forecast. Stop halfway, take a break to fight fatigue and stretch your legs before tackling the last portion of the flight. Choose a different airplane, one with greater range or better fuel economy. Plan to have at least an hour’s fuel remaining when you shut down at the destination. Stop en route if you start eating into that reserve.

6. Faster is better.

If 180 hp is the minimum for cross-countries, it’s implied that more horsepower is better. The same is true when it comes to cruising speed. And not just because you arrive quicker.

Greater speed means you can accept a spirit-deadening headwind and complete relatively short trips without a fuel stop. It means you can cover a lot of territory—and see a lot of weather—in just three or four hours. Most important, it means you can fly around, outrun or outmaneuver more easily the kind of weather that would otherwise keep you on the ground or holed up short of your destination when flying a slower airplane.

One rule of thumb often overlooked when choosing among piston-powered single-engine airplanes of the same basic configuration is that it can take the same amount of fuel to get from Point A to Point B no matter what you’re flying. For example, I once flew my 285-hp Debonair along the same route and at the same time as a friend in his 180-hp Comanche. Our fuel burn was within three gallons of each other, but it took me only three hours versus his four. Greater speed offers obvious implications for minimizing fatigue, too.

7. Higher is better.

As a letter in [the February 2019 issue] highlights, flying cross-countries at relatively low altitudes in a single doesn’t make much sense. Flying high in that same single affords you much more time to find a place to land or resolve the problem when an engine acts up. There’s less traffic and you’ll burn less fuel in cruise once you get there. If that’s not enough, there are other reasons to get as high as you can.

One of them is for a smoother ride, in clearer, cooler air. In the summer, it might take a while to climb on top of the haze layer, but the benefits are worth it, especially since doing so allows you to more easily see the way cumulonimbus clouds are arranged and plan your route around them. At lower altitudes, haze and other reductions to visibility can mean stumbling into a situation you don’t want and can’t handle. Climbing to maximize a tailwind’s benefits can also push you beyond poor weather more quickly than if you have to slog through it down low.

The only two downsides of using a higher cruising altitude is the possible need for supplemental oxygen and the greater amount of time it will take to get down in a hurry if you need to. Well…that and discovering how inadequate some cabin heating systems can be during the winter.

PILOT

After we mitigate the risks imposed by poor weather and resolve mechanical or equipment issues with the airplane, what’s left falls into a big bucket labeled “pilot-related.” That means you.

8. How are you feeling?

Launching on a four-hour flight after a full day at the office isn’t the smartest thing I’ve done. Especially when getting eight hours and launching at zero-dark-thirty to make it on time to a distant appointment is an option. The truth is we often fly when we’re less than 100 percent. The challenge is to ensure the 10 or 20 percent of human performance we might be lacking won’t be needed on a given flight. That’s hard to do on almost any flight but the simplest milk run.

9. Are your skills up to the task?

Tackling low IFR at your destination, busy terminal airspace, a complicated departure procedure or an inflight emergency without the necessary skills is a recipe for disaster. While we probably have learned how to do all that at one point or another, it’s likely to have been a while since we practiced some of the skills needed to pull it all off. Yet we can be confronted with all that and more almost any day.

Get frequent training in these and other areas. Some might say a goal of such training would be to pass your checkride on any given day, and that’s a worthy objective. But the real goal is that the flight’s outcome is never in doubt.

10. Imagination is the limit.

The last item on this list isn’t as objective as the others. Instead, it’s a challenge for you to think outside the box a lot of our training puts us in. The previous nine tips comprise options, whether in planning, choice of aircraft and equipment, or in how we prepare ourselves for the task.

Some proposed flights simply can’t be accomplished on the day or time chosen, with the airplane you have and the condition in which you find yourself. It’s the wise pilot who accepts this reality and lives to fly another day. That same wisdom also tells us that some flexibility and compromise, along with a little imagination (and plenty of fuel!) might allow us to complete the mission anyway, no matter what the aviation gods throw at us.

Jeb Burnside is this magazine’s editor-in-chief. He’s an airline transport pilot who owns a Beechcraft Debonair, plus the expensive half of an Aeronca 7CCM Champ.