Near Hernandez, N.M., headed south, I noticed the moon rising to my left. It reminded me of Ansel Adams’s iconic 1941 photograph, Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico. I took out my phone and tried to snap a picture. My more artistic friends might be amused by the effort.

Adams used a large-format camera with a very long exposure. Details on the ground are clear. There’s a tiny village surrounded by scrub land, with hills visible in the distance. My quick exposure through a glare-filled pane of Plexiglas showed none of those details. The ground was completely dark, even though the moon was up.

Pilots are comforted by moonrise, by sunrise even more. When I was a young pilot, an old pilot said to me, “Only us old guys know the phase of the moon. That’s why we’re old.” Another old pilot advised me about flying into strange mountain airports at night: “After an eight-hour preflight,” he suggested. I took that advice to heart. I expected to see the moon rise that night. I did not expect what happened next.

COMPLACENT MUCH?

Charter pilots go when and where requested, retaining the right to say “no” to more outrageous requests like Aspen, Colo., on a dark night. But Aspen has alternatives nearby; my destination did not. It was a strange airport surrounded by scrub, with hills visible in the distance, at least according to the sectional chart and some Google mapping. AWOS. Instrument approaches from the south, none from the north. Should be a piece of cake.

Can you smell the complacency settling in?

The AWOS said “wind calm.” Getting close, I clicked on the runway lights. All I could see was the outline of one runway. No approach lights. No crossing runway. And no lights on the ground. None. A black hole. Dark as the inside of a cow.

I chose to overfly the runway and enter left traffic to Runway 13. The alternative was to fly the RNAV approach to Runway 31, but that would have added 30 miles to the flight. (Somebody please explain to me why pilots hesitate to add 10 more minutes to a flight. Those who fly for pay will make extra money that way, and those who fly for pleasure get more time in the air. I suppose this is a variant of get-home-itis.)

This night, the wind may have been calm on the ground, but it changed from smooth to turbulent as we descended to traffic pattern altitude. Not just bumpy: moderate-to-severe turbulence. Stall-warner-chirping turbulence. Things-flying-around-the-cabin turbulence. That little rectangle of light was the only ground reference and it refused to stay still. That meant it was no reference at all.

Past abeam the numbers on downwind, even the little rectangle of light was out of sight. There was nothing to see. The only option was to use the instruments to fly an approximate heading on base leg and try to keep a reasonable descent rate (see the sidebar at right).

I wrestled the airplane onto final and watched that little rectangle bounce around until about 50 feet agl. The AWOS hadn’t lied: the wind on the ground was calm.

To say the least, I was disappointed in this approach. They say that any landing you walk away from is a good one, but there’s more to landing than the touchdown. The passengers were shaken. I was pretending not to be.

There are two styles of instruction. One tells people what to do; the other tells them how to do it. Usually the latter is more effective, but not always.

Student pilots are taught a sequence of primary and secondary control manipulations to get from downwind to touchdown: pitch, power, flaps, trim, perhaps landing gear. That works, although the “what to do” part is checked with airspeed. If the airplane starts at the correct speed on downwind, adding an increment of flaps and retrimming gets the airplane close to the desired speed on the next leg. Rinse, repeat.

During the day there are lots of opportunities to judge height. In a black-hole approach, though, they aren’t there. The best method, then, is to set up a reasonable descent rate. But what number is that?

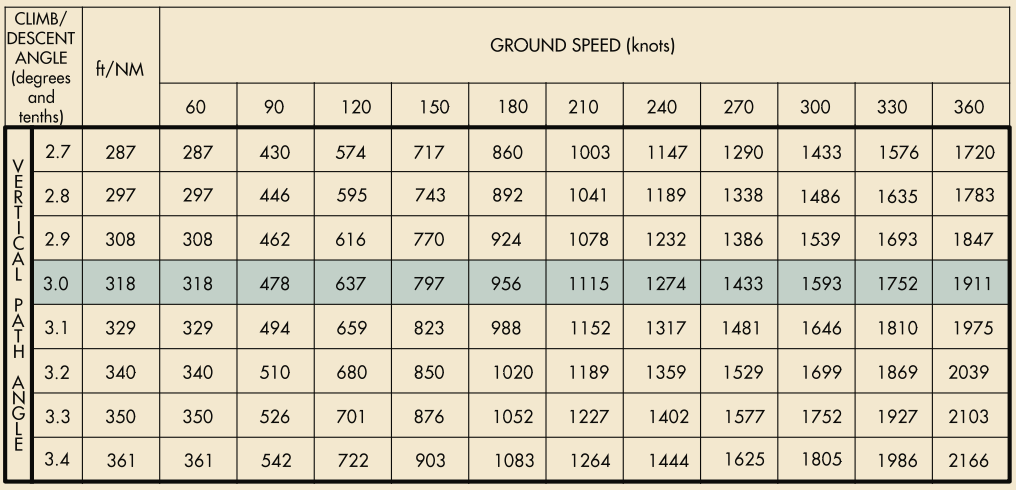

A three-degree glidepath results in the vertical speed being roughly five percent of the horizontal speed. For a three-degree glidepath, just halve your groundspeed and add a zero. The graphic above, adapted from the FAA’s climb/descent rate table, tells the tale. If groundspeed is 120 knots, vertical speed should be about five knots, or 600 fpm. At 60 knots groundspeed, vertical speed should be about 300 fpm to maintain the three-degree glidepath, and the values for other groundspeeds can be interpolated.

WHAT WENT WRONG

This was a “black-hole” approach, one with no peripheral ground references helping provide an altitude reference. The lack of altitude reference increases the risk of flying into the ground or hitting an obstruction. The additional lack of attitude reference when you need to be flying visually increases the risk of losing control of the airplane close to the ground. This is serious business. Loss of control and controlled flight into terrain are leading accident causes.

There are many situations that can lead to a black-hole approach. It is a perfect background (or lack thereof) for visual illusions, as described in the FAA Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge (PHAK, FAA-H-8083-25B). Let’s go over them in context.

The first is the autokinetic effect, apparently first observed by Alexander von Humboldt in 1799. “Kinetic” refers to movement. A single light in a dark background appears to move on its own (that’s the “auto” part), even though it is sitting quite still. Using a light like this as a reference won’t work, because you would tend to follow the apparent motion.

You cannot use a single light to judge attitude. That’s pretty easy to understand. If you could do a perfect roll around a single light source, you wouldn’t see any change at all through all 360 degrees. That’s an easy way to lose control of the aircraft.

Sometimes, though, a single light on the ground is a streetlight, and if there is something in the air like light dust or light fog, you can see the cone of light and even a fairly large circle on the ground, if you are low enough. That’s pretty desperate, but one of my friends claims that this saved him from a loss-of-control accident many years ago.

Approaches over water present notorious black-hole conditions. There are few if any lights, and those might be on moving boats. Not much to go by there. Larger airports with overwater approaches, have expensive approach light system, which are unlikely at the airport nearest your sister-in-law or potential customer, which might see only a handful of night operations each year.

Just as bad as water is something like open, flat land with few lights on the ground. Even a full moon making it light enough to read on the ground won’t really get you any usable information from the air.

In addition to autokineses, the PHAK describes the problem of false horizons. Those lights from the town 10 miles from the airport can look a lot like a horizon, but it’s not a usable horizon. Even airports near towns or other built-up areas can have black hole portions in the traffic pattern. Turning crosswind might mean turning away from the lights and facing the void, and turning downwind doesn’t always bring the lights into view again.

The opposite of the black hole approach is the whiteout approach. One is Yin; the other is Yang. They’re both difficult.

A whiteout is when a low or even low-ish overcast makes it difficult to judge attitude. One example might be flying over open water with limited visibility. Another might be flying over snowy ground under an overcast sky. In these cases there is no visible horizon, especially at dawn or dusk.

This pretty much describes the situation John F. Kennedy, Jr., encountered in his Saratoga SP in July 1999. It was dark, the airplane was over water and visibility was low: The natural horizon wasn’t visible. I had flown that exact route a few times before, but I flew it IFR. Among other things, that means an alarm would go off at the ATC facility if I started to lose altitude, adding a layer of protection. Not yet instrument-rated, JFK, Jr. evidently did not ask for flight following, which might not guarantee a low-altitude warning but would still provide another layer of watchfulness that could have prevented his crash.

WHAT WENT RIGHT

To say the least, I was disappointed in this approach. But what can I and other pilots do to make the black-hole approach less uncomfortable?

First, get rid of the idea of flying a few miles past the airport to enter downwind “on a 45.” I don’t like this in any case. In good VFR day conditions, it’s inconvenient, but at night over blank terrain, it means flying into an unknown area that you cannot see. Obstructions may be unlit. It is safer to overfly the runway at pattern altitude in the landing direction and then fly crosswind, downwind and base legs. That way you always have a pretty good idea of where you are. In many ways, the situation is like a circling approach after an IFR approach. (See “The Lost Art of Circling,” Aviation Safety, May 2021, and Daniel L. Johnson’s comment from the July 2021 issue.)

One of the risks of any night landing, but especially into a black-hole runway, is running into something we can’t see. To ensure the only thing we hit is the runway, it can pay to stay high. When on final and the runway lights start to dim or disappear, go around, you’re too low.

GOING AROUND

Even if you do everything perfectly, you might have to go around. Pilots should always be ready to go around, and it’s arguably more likely at night. You won’t be able to see the deer or the antelope or the disabled airplane or the torn-up runway (remember Meigs Field, which the city of Chicago tore up one night?) until you are almost in the flare. The simplest plan is to act like you’ve just done a touch-and-go and enter the charted traffic pattern to try again. But this isn’t always the best plan, especially at mountain airports.

A better plan is to fly the missed approach procedure for the runway’s instrument approach, but this may not work, either, because you might be starting from well below the minimum descent altitude (MDA). Missed approach procedures assume that you are at or above the MDA when you decide to miss, so this technique does not guarantee that you will clear all obstacles.

Even better would be to fly the departure procedure for your runway, which assumes that you cross the far end at 35 feet agl. It also assumes that you climb well, or may require specific climb performance.

That is a lot of talk about instrument procedures and charts and techniques, even if the airport has good VFR weather. Here’s the uncomfortable fact: it is never VFR at a black-hole airport.

One of the main “features” of the black-hole approach is the pilot’s inability to accurately gauge altitude. This makes it difficult, if not impossible, to correctly time a traditional flare maneuver at touchdown. Initiate the flare too late and you risk pranging the nosewheel. Too early and the chance you’ll stall too high above the runway for a smooth touchdown greatly increases, as does the risk of losing control. The solution I was taught? Establish the nose-up flare attitude well above the runway and fly that attitude all the way to touchdown. I was told this maneuver was dubbed a “carrier landing,” probably by someone who never landed on an aircraft carrier. It’s similar to a seaplane’s glassy-water approach.

The technique is rather simple: After turning final and with the before-landing checklist complete, and the airplane properly configured, slow to your desired “over-the-fence” or short-final airspeed. In my Debonair, that’s 70 KIAS, a speed that should work for many piston singles. Establish a nose-up (flare) attitude at that airspeed and manage the descent rate with power. As discussed in the sidebar on page 17, descent on a three-degree glidepath should be about 350 fpm. Maintain the desired speed, attitude and descent rate until the mains hit the runway, perhaps rather firmly.

This is basically a behind-the-power-curve, slow-flight maneuver, but with the desired descent rate built in. As such, it’s best to practice it at altitude in daylight, and then throw in maintaining the desired attitude, speed and descent rate to a landing before trying it at night. — J.B.

UNATTENDED

It’s a good bet that if an airport has a black-hole approach it is unattended at night. It’s easy to check this in the Chart Supplement (formerly the Airport/Facility Directory, A/FD) or any EFB. The airport manager’s telephone number typically is part of this information. But doesn’t it seem like people are more and more reluctant to answer phone calls from unknown numbers? If you need anything—fuel, ground transportation, restrooms, whatever—you can call but you will probably need to leave a voice message and hope that the manager checks for messages regularly. This goes a lot better if you call in advance.

CALM ON THE GROUND

In retrospect, I did all the things that night that I’ve recommended here. The moon was out. I had a good circling plan that kept me at a reasonable distance from the airfield. When attitude control got difficult, I concentrated on the instruments. My company had, in fact, called ahead to arrange a rental car, which was waiting on the ramp.

But, the moon was not shedding any useful light. Conditions made it more difficult to stick to the circling plan, in part because it was really hard to judge attitude. Of course, the rental car had a flat tire. But that’s not an aviation hazard.

The unexpected element was the turbulence. What does that have to do with the black-hole approach? At a busier airport you might have known the turbulence was lurking below you, but not on that night. At a quiet airport without many night operations, who is going to give a pilot report?

In a way, approaches to these airports are easier when the weather is near IFR minimums. No judgment is necessary: you have to fly a published instrument approach, even if that adds dozens of miles to your trip. Someone at the TERPS office has made a circling plan for you. Nowadays, it is very likely that you have some kind of autopilot that will help fly the approach. If you’ve called ahead, the building will be open, the heat will be on and there may even be some fresh coffee or something to get your spirit back to Earth.

The picture I took from the cockpit of the moonrise over Hernandez was blurry and jumpy. I deleted it.

Jim Wolper is an airline transport pilot and retired mathematics professor. He’s also a CFI with single-engine, multi-engine, instrument and glider ratings.