Every year, the Montana Department of Transportation Aviation Division offers its well-attended and comprehensive Surratt Memorial Winter Survival Clinic. Just about every pilot who has attended raves about the experience, and, thankfully, the majority in attendance will never have to apply the survival skills outlined at the clinic. Little did one pilot know that only weeks after his attendance at the clinic would he be neck-deep in snow, fighting for his life.

It was a crisp, late March evening in Billings, Mont., when the 18-year-old pilot intended to knock out some solo cross-country and night requirements for his commercial pilot certificate. He planned to head south to Powell, Wyo., about 60 nm south-southwest of Billings, and return. The pilot thought he might even be able to squeeze in some night landings once back at Billings.

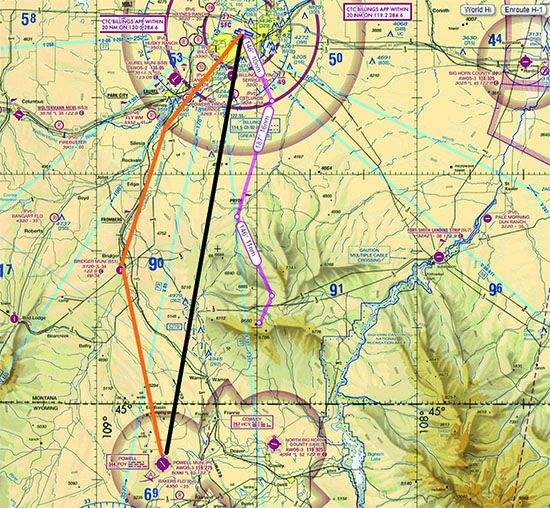

Per the commercial pilot syllabus, navigation was to be conducted via pilotage and ded-reckoning, even though the Piper PA-28-181 Archer II/III was fully equipped with an Avidyne glass panel driven by dual Garmin 430 GPS units. It was expected the flight was to be conducted without using the autopilot. The pilot’s planned route was to depart the Billings area to the southwest, and then follow state route 310 south past the Bridger airport, with a turn toward Powell for the final leg. By following such a route, the aircraft would remain comfortably within a valley between the Pryor and Beartooth mountain ranges.

Checking the weather for the short flight, the pilot discovered the Montana portion of the flight showed no weather of concern. The Wyoming forecast included some isolated snow showers as well as an Airmet for icing and mountain obscuration—not uncommon for the region that time of year. The pilot filed a flight plan for the flight down and one for the flight back.

THE FLIGHT

Around 2100 local time, the Piper departed the Billings airport, initially being assigned a 130-degree heading while climbing to a VFR cruising altitude of 7500 feet msl. After clearing the Billings airspace, the pilot resumed his own navigation. Soon afterward, the pilot opened his VFR flight plan.

The pilot had just earned his instrument rating and had a total of 150 hours, with 60 hours in the Archer. The pilot was very active, with 21 hours of flight time in the past 30 days. The instrument rating and recent experience likely provided some comfort in taking a solo night cross-country in the forecasted conditions in a mountainous region.

Contrary to his original plan, the pilot set up the GPS to navigate directly between Billings and Powell. Being on an assigned heading after takeoff took the aircraft further east than was anticipated, so the pilot manually programmed a course in the GPS. Recalling his planned true course of 192 degrees, the pilot programmed the GPS to track this value and engaged the autopilot.

During his GPS programming, the pilot did not consider an allotment for magnetic variation, which was around 13 degrees east. Thus, the correct setting for the GPS would have been a track of around 179 degrees. One result of using the wrong numbers was that the lateral clearance of the Pryor Mountains was reduced from approximately 12 nm to less than five.

Around 15 minutes into the flight, the aircraft encountered snow showers and reduced visibility. The pilot decided to seek better VFR conditions by disengaging the autopilot and turning left to 155 degrees. He remained on this heading for seven minutes, traveling several miles further to the east and bringing the aircraft even closer to rising terrain. Eventually, the aircraft was turned to a 195-degree heading. Possibly becoming concerned about his actual position, the pilot pulled out the local sectional chart to assess the nearby terrain. The pilot surmised he was at least 800-1000 feet above the ground.

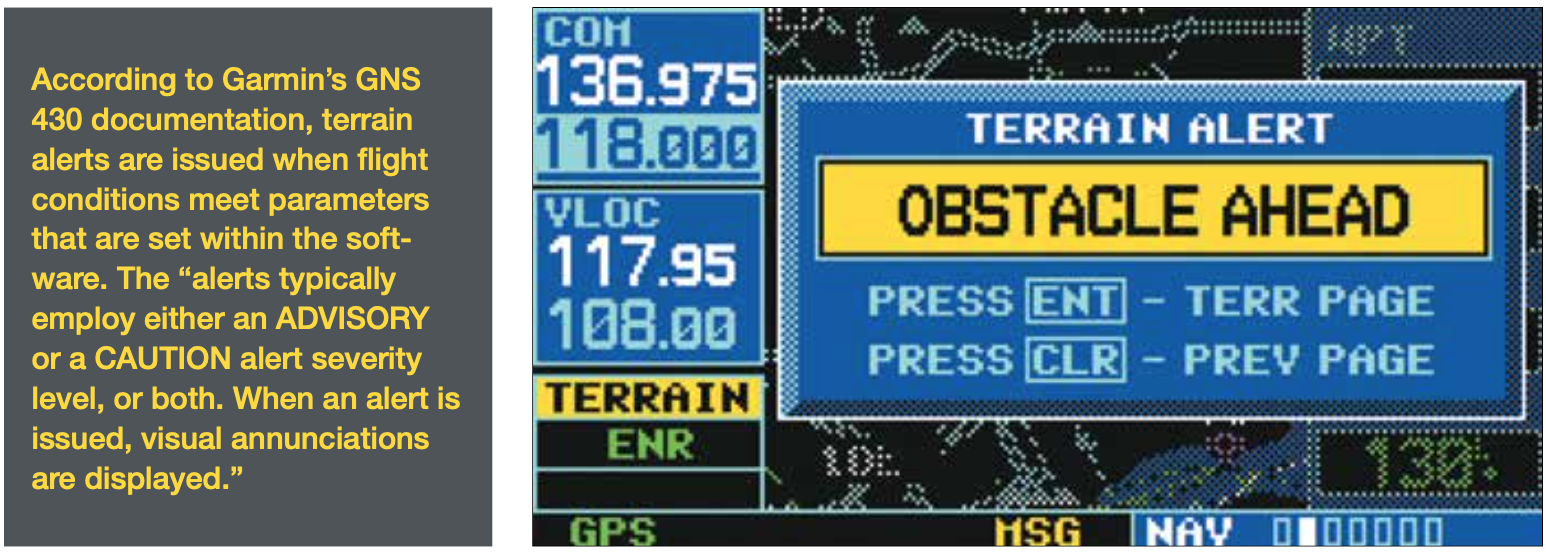

Following another 10 minutes en route, the pilot noticed a flashing message on both GPS units. When the pilot focused his attention on the GPS, he realized the notice was, in fact, a terrain alert. He immediately began adding power and turning. At that point, he lost consciousness. The aircraft impacted terrain at about 7400 feet msl in an area where the terrain elevation rises to over 8600 feet.

POST-CRASH

Coming to, the pilot surveyed the scene. First, he realized he was lucky to be alive, especially since the co-pilot’s seat was completely crushed. Next, he turned off the master switch and ensured the ELT was “on.” Wearing only shorts, since he expected to be in a warm cockpit for the night, the pilot quickly became quite cold. He decided to hike up to the highest point he could see, but as he left the airplane, he sank up to his neck in deep snow. Now frigid, he returned to the aircraft. At this point, the pilot appeared to begin applying those winter survival skills he learned only weeks ago.

Thanks to this training, he was very familiar with the supplies in the emergency kit on board the aircraft. He put on his hat and gloves and retrieved the thermal “space blanket” from the kit, and huddled down in the cockpit for the night. Blowing snow soon became an issue prompting him to move back into the tail section, just as he had done at the training course. At some point during the night, the pilot also shot off two flares, which apparently went unnoticed.

Very happy to see the sun in the morning, the pilot was able to send a text message to his instructor: “I’ve crashed and I am alive.” He then was able to place a phone call to the flight school to explain what happened and that he was still with the airplane. Soon thereafter, he heard a search aircraft. He quickly turned on the avionics and successfully reached the search crew via the radio, though it only worked for around 10 minutes. The pilot donned an orange tarp from the survival kit to become more visible. After being sighted, a helicopter moved in to retrieve the pilot off the mountain. Besides a few scrapes, a touch of frostbite and a bruised ego (and a few other bruises), the pilot was in pretty good shape.

I’m always fascinated by the motorcyclists I see cruising through town in shorts, flip-flops and a do-rag. When I ride a bike on the street, I’m geared up. When flying over inhospitable terrain, you should be too. The old saying among pilots roughly is, “Dress for the terrain and weather underneath you.” This from someone who once airlined over the North Atlantic in shorts.

You get to be the judge of what’s appropriate. The one thing you should be aware of is that all the survival gear in the world won’t help if it doesn’t get on the airplane or isn’t accessible when there’s a mishap. — J.B.

LESSONS LEARNED

The accident was a combination of two circumstances that typically are fatal by themselves: VFR-into-IMC and controlled flight into terrain (CFIT). Luckily, this pilot was able to literally walk away from the ordeal. It also was entirely preventable. In fact, this accident features a classic chain of errors that led to the near-lethal crash.

The pilot set himself up for the loss of situational awareness in several ways. He planned his flight to rely on ded-reckoning and pilotage but seemingly never intended to fly the planned route. The pilot admitted never seeing any of his proposed VFR checkpoints.

Lesson: Stick to the plan. Improvising your route at night in the vicinity of mountains is unwise, to say the least. More altitude would have helped.

Even a GPS-direct route from Billings to Powell, as the GPS was set to do at takeoff, would have kept the pilot out of trouble, but he neglected to follow through. Next, the pilot erroneously entered his planned true, instead of magnetic, course as the track to follow. This, coupled with being sent further east during departure, brought the route closer to terrain, unbeknownst to the pilot.

Lesson: If you plan to use technology, be sure you know how to use it properly.

Because of the cumulative decay of situational awareness, exacerbated by the comfort of the autopilot being engaged, when the pilot encountered IMC, he turned left toward rising terrain. By making this choice, the pilot put the airplane on a collision course with a mountain when turning back toward the destination.

Lesson: Loss of situational awareness is an emergency—never accept “guesstimates” of position, especially at night.

Thankfully for this pilot, he was able to keep himself warm enough during an overnight snowstorm to avoid severe frostbite, hypothermia or even death. Pilots should always have the clothes and equipment appropriate for the weather and terrain they will encounter during their flight. Sub-zero overnight temperatures call for something more than shorts. Extra layers and a heavy jacket are just as necessary as a life jacket would be for extended overwater operations.

Lesson: Dress the part—be prepared for the worst, just in case.

RISK-MANAGEMENT LESSONS

The outcome of this VFR-into-IMC/CFIT event clearly could have been a lot worse. It also provides an example of how impulsivity (e.g., abandoning the planned route) and invulnerability (e.g., wearing shorts) can seep into any cockpit. This accident certainly supports the notion that pilots can reap big benefits from continuing specialized education and training, like winter survival training. You never know; it just may save your life.

To ice the cake of this “happy” outcome, the pilot immediately got back on the horse and is now working for the airlines.

Lesson: Despite adversity, never give up.

Dave C. Ison, PhD, has over 6000 hours of flight time, holds ATP MEL, commercial SEL/SES certificates, and is an instrument and multi-engine flight instructor.