Stop me if you’ve heard this story before. Some of the details may vary here and there, but the general plot is always the same. I had a morning departure time, right in that sweet spot where you are going to hit rush hour traffic no matter what time you leave. We rush to get the airplane pulled out, fueled and stocked. Complete the preflight, the paperwork and a quick recheck of the weather and Notams, and we are ready to go.

Now we are waiting for the passengers. The departure time comes and goes. About 45 minutes later, the passengers show up, disheveled and clearly ready to go. Murphy’s Law kicks in, and despite probably 1000 successful starts in a row, we get a hung start. Now we must tell the already-late passengers that we have to swap aircraft. The whole process begins again, only somehow the pressure to rush is even higher.

We get everything done, a new preflight, swapped the catering and bags, the whole deal. My captain and I were going through the cabin when I asked if he was ready for passengers. He sat me down in a seat, took out his phone and started a timer. Sixty seconds. We just sat in the seats and reflected on the flight ahead, no talking or additional prepping. In that time, several things were accomplished. Both of us remembered something we had forgotten, and we were able to reset the “rushing mentality” that so insidiously creeps in.

SIXTY SECONDS

There is a sort of beauty in one minute. The passengers will not miss it, despite their existing delay. Weather will not change that much in one minute—if the difference between departing or delaying for weather is down to one minute, delaying is probably the right choice. If you are in a rush, a minute goes by in a blink of an eye. Once you take away the rush, it is sufficient time to reflect and let your brain catch up with everything that is happening.

This event has stayed with me my entire career, and I have used the same trick multiple times during scenarios where I could feel myself beginning to rush. It has saved me from regulatory risk, such as forgetting paperwork or a critical Notam. Risk mitigation does not just boil down to accident prevention; scenarios such as avoiding an airspace deviation are an important use of these strategies. These are some of the first things to go when external pressures are mounting.

EXTERNAL PRESSURES

External pressures are influences not directly related to the operation which create a sense of pressure to complete a flight, often at the expense of safety. This is the E in the PAVE acronym (Pilot, Aircraft, enVironment and External pressures), and there are several quality recommendations to mitigate them in various FAA publications. Many of the external pressures, such as get-there-itis or the fear of disappointing passengers, are frequently listed as contributing factors on NTSB reports. We are all aware of the existence of these troublesome factors, but I am lying if I say that I do not feel myself begin to relax on my go-home leg or that I do not feel the urge to rush if a passenger has a commitment to make.

Taking a deliberate step to reset your brain can break the link in the chain that leads to an accident or incident. In the story related earllier, I mentioned how both my captain and I remembered something we had forgotten while we were rushing. Anything from regulatory risk, like forgotten paperwork, to something more severe, like a missed Notam for a closed runway. Ask anyone who has had a violation, accident or incident if there was a one-minute period of time in the lead-up to the event where a few choice decisions could have changed the outcome. I would bet there almost always is.

According to the FAA’s Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge (FAA-H-8032-25B), external pressures are “the single most important key to risk management because it is the one risk factor category that can cause a pilot to ignore all the other risk factors.” Frequently, these factors create and exert time-related influence on our planning, thinking and prioritization. They can be like a pressure-cooker on a stove, and having a set of iron-clad standard operating procedures can work as a relief valve. The FAA recommends these procedures can include but are not limited to:

*Allow time on a trip for an extra fuel stop or to make an unexpected landing because of weather.

*Have alternate plans for a late arrival or make backup airline reservations for must-be-there trips.

*For really important trips, plan to leave early enough so that there would still be time to drive to the destination, if necessary.

*Advise those who are waiting at the destination that the arrival may be delayed. Know how to notify them when delays are encountered.

*Manage passengers’ expectations. Make sure passengers know that they might not arrive on a firm schedule, and if they must arrive by a certain time, they should make alternative plans.

*Eliminate pressure to return home, even on a casual day flight, by carrying a small overnight kit containing prescriptions, contact lens solutions, toiletries, or other necessities on every flight.

One of the keys here should be to accept delays: It’s a rare event when we travel by any means that we don’t encounter delays. The pilot’s goal is to recognize and manage the risk external pressures create, not to ignore it. — J.B.

TAKING IT TO THE AIR

This philosophy is not just for use on the ground. While I do not recommend actually starting a timer in the cockpit and waiting for it to expire to take action, there is benefit to a measured, thoughtful response. A cliché in survival training is the Rule of Three: You can survive three weeks without food, three days without water, three minutes without oxygen and three seconds without panicking. In the end, just like an abnormality or emergency in an airplane, preventing that extreme fear and keeping composure for the first three seconds is most critical to a safe outcome.

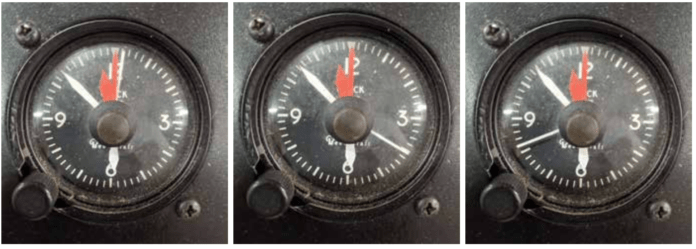

My first ground instructor in an advanced aircraft used to preach the “one sip, two sip” rule. The aircraft had an annunciator panel with red warning messages, yellow caution messages and green status messages. If you got a red message, you would take one sip of coffee to identify, verify and prevent erroneous responses. A yellow message, usually more advisory in nature, warranted two sips of coffee before reacting. I use both of these adages to help prevent panic. If I don’t have a cup of coffee handy, I take a full deep breath or two before reacting.

I will discuss some exceptions to these rules at the end because there are absolutely some emergencies that require immediate corrective action. However, most failures and circumstances can persist through the inevitable startle factor and a brief moment to regain composure without degrading safety. Now I am going to bring up another aviation cliché, and bonus points if you can guess it: Aviate, navigate and communicate, the Holy Trinity of task prioritization for pilots in dire circumstances.

There are scenarios that absolutely require immediate, ingrained action. These scenarios should be practiced frequently and reviewed anytime you are flying a new or different airframe.

Takeoff and Climb

If you’re anything like me, the first time your MEI pulled an engine on the takeoff roll was an eye-opening experience. Despite a thorough preflight briefing, I was not prepared to deal with how fast the aircraft started veering off the runway. I had to train for the proper response. Once it became muscle memory, the maneuver went much more smoothly.

Single-engine airplanes are not immune to this. A complete engine failure just after rotation will require significantly reducing the back pressure, if not actually pushing down on the yoke. A controlled crash is much more survivable than a stall/spin, loss-of-control accident.

Landing

Go-arounds and missed approaches should be second nature. They can involve a lot of aviating, navigating and communicating, often all at the same time. Frequently the reason for going missed, such as traffic or weather, will take up a significant portion of your bandwidth. Maintaining proficiency is key.

AVIATE…

The first step takes place immediately after your sip of coffee when a failure or emergency occurs. During sim training, an instructor pointed out to me that I articulated it, even though it was not intentional: I would ensure that I had control of the aircraft and say, “Okay, the aircraft is flying.” There is no sense in moving on to the next step if the previous one is not complete. An example of this is an engine failure in a multi-engine airplane. So long as you are above VMC and at a safe altitude, attempting to quickly rectify the problem can lead to more disastrous results than just flying the airplane. Pilots at all experience levels have successfully shut down or attempted to secure the functioning engine, altogether removing its benefits.

…NAVIGATE, COMMUNICATE

Once you have control of the aircraft, you can move on to navigating and communicating. Especially when low to the ground and/or in mountainous terrain, it is critical to get the aircraft pointing in the right direction. If you are already in controlled airspace and communicating with ATC, you can knock out both of these priorities at the same time. Declaring an emergency, and requesting an altitude and vector, can be an effective way to reduce workload and allow you to refocus on managing the aircraft. There absolutely are scenarios where this is not possible, such as a missed approach or departure procedure in terrain and outside of radar and radio coverage. Therefore, it is critical to fully brief every procedure you intend on flying, because you never know when you may have to manage flying it with 95 percent of your mental bandwidth occupied by a serious mechanical issue.

The glue that holds this philosophy together is that it is more prudent to take your time and react appropriately. Failing to do so can allow any pilot to fall into the trap of extreme fear, which can create a feedback loop where bad information can lead to an improper response.

A simplified example of this is Air France Flight 447. Bad air data led to the aircraft being placed in a nose-high condition, stalling the Airbus A330. It lost altitude, which the pilot flying attempted to correct by adding back pressure, worsening the stall condition. This scenario was not trained in the simulators, so the crew were not equipped to deal with it. It’s easy to Monday-morning-quarterback this crew, but had they taken a sip of coffee or two prior to adding back pressure, the situation would have been more manageable.

I may have mentioned the importance of training once or twice throughout the article. Training in aircraft and even in advanced simulators have limitations. In the airplane, you are limited to whatever risk threshold you and your instructor are comfortable with. There is no sense practicing maneuvers that put you and your aircraft in a position of undue risk. In simulators, you are at the mercy of programming. They are phenomenal tools but they only model known, existing failures.

While you cannot go out and practice an in-flight fire or ditching, being aware of the procedures and chair-flying it can be the difference if someday your luck runs out. Passengers can assist too, opening emergency exits or grabbing emergency equipment such as flares or life preservers. A mentor of mine used to periodically have his family practice a quick egress, sorting out issues like who would exit first and how to facilitate getting someone out of the back seat. This can be a fun thought exercise or great subject of hangar talk, and it may even save your life someday.

THE EXCEPTIONS

I am sure many can immediately think of 10 scenarios where taking a minute would be not only poor ADM, but potentially catastrophic. A few of them are discussed in the sidebar on the opposite page. In such scenarios, it is critical that the response is trained and ingrained. Ultimately, if you are faced with an unknown and there is either no procedure or no time to consult your checklist, you are left with a best guess, and trial and error. Frequently, a task-saturated mind will not come up with the most prudent guess and the trial and error process will worsen the situation or create an entirely new undesired aircraft state.

Taking your time to process all available information will, at minimum, prevent you from worsening the situation and gives you the best shot at recovery. Training and procedure are every pilot’s best bet at preventing a catastrophic result in an emergency, but there is no exact footprint for navigating every situation. No two are exactly alike. Keeping a cool head and avoiding mistakes is a fantastic first step toward getting the aircraft safely on the ground.

Ryan Motte is a Massachusetts-based Part 135 pilot, flight instructor and check airman. He moonlights as Director of Safety when he isn’t flying.