The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) is formally asking the FAA and the National Weather Service (NWS) to take steps designed to improve the accuracy of automated weather observations by addressing equipment malfunctions in a more proactive manner. The requests come as the NTSB completes its investigations into the February 15, 2019, fatal crash of a Cirrus SR22 near Ely, Nevada, and the sinking of an amphibious passenger vessel on July 19, 2018, near Branson, Missouri. Seventeen of the 31 occupants aboard the WWII-era “Duck” being used as a tour platform died when it began taking on water in a storm.

According to the NTSB, the SR22 had diverted to Ely in part because the airport’s automated surface observing system (ASOS) was reporting nine miles of visibility in light snow at the time, even though ground witnesses later reported heavy snow with visibility ¼ to ½ mile at the time. According to the NTSB’s evaluation of weather conditions at the time of the accident, “ASOS visibility reporting at [Ely] had, at times under various weather conditions, not been accurate for weeks before the accident and had been a concern for pilots operating at the airport.”

“After the pilot performed a go-around because he was unable to see the runway to land, the airplane impacted upsloping mountainous terrain in a relatively level attitude,” the NTSB said. The investigation did not find any mechanical anomalies precluding normal operation.

In the Branson, Missouri, vessel sinking, the NTSB’s investigation estimated that the nearest automated weather observing system’s (AWOS) clock was slow by about 7, 8, or 9 minutes during the day of the accident. The Board determined the AWOS clock drift was not a factor in the sinking but that it “represents a potential safety issue in that it can negatively affect transportation operators’ situation awareness and decision-making.”

As a result of its investigations into these accidents, the NTSB formally recommended that the FAA and NWS “address various concerns with malfunctioning automated surface observing systems (ASOS) and automated weather observing systems (AWOS), as well as their respective reporting capabilities, which can result in erroneous weather information being provided to the transportation community.”

“Accurate weather information is vital support for safety-related decision-making in all modes of transportation,” the NTSB said in its report.

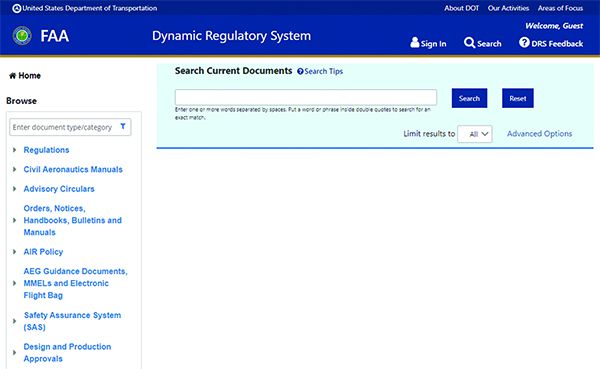

A new online resource from the FAA, its Dynamic Regulatory System, is designed to enhance access to its regulations, handbooks, Advisory Circulars and many other documents by placing links to them in one place, rather than scattered over several locations on the agency’s web site. The new site, available at drs.faa.gov, also serves as a portal for accessing aircraft maintenance and certification data, including STCs and PMAs.

PILOT’S DECISIONS LET TO KOBE BRYANT CRASH

In a probable cause finding that surprised almost no one, the NTSB determined the January 26, 2020, crash of a Sikorsky S-76B helicopter in Calabasas, California, that killed basketball star Kobe Bryant, his daughter Gianna and seven others including the pilot, resulted from the “pilot’s decision to continue flight under visual flight rules into instrument meteorological conditions, which resulted in the pilot’s spatial disorientation and loss of control. Contributing to the accident was the pilot’s likely self-induced pressure and the pilot’s plan continuation bias, which adversely affected his decision-making.” The Board also found that Island Express Helicopters Inc., the helicopter’s operator, failed to provide adequate “review and oversight of its safety management processes.”

“About two minutes before the crash, while at an altitude of about 450 feet above ground level, the pilot transmitted to an air traffic control facility that he was initiating a climb to get the helicopter ‘above the [cloud] layers.’ The helicopter climbed at a rate of about 1,500 feet per minute and began a gradual left turn,” the NTSB said in a press release. “The helicopter reached an altitude of about 2,400 feet above sea level (1,600 feet above ground level) and began to descend rapidly in a left turn to the ground. While the helicopter was descending the air traffic controller asked the pilot to ‘say intentions,’ and the pilot replied that the flight was climbing to 4,000 feet msl (about 3,200 feet above ground level). A witness first heard the helicopter and then saw it emerge from the bottom of the cloud layer in a left-banked descent about one or two seconds before impact.”

“Unfortunately, we continue to see these same issues influence poor decision making among otherwise experienced pilots in aviation crashes,” said NTSB Chairman Robert Sumwalt. “Had this pilot not succumbed to the pressures he placed on himself to continue the flight into adverse weather, it is likely this accident would not have happened. A robust safety management system can help operators like Island Express provide the support their pilots need to help them resist such very real pressures.”

IS A NEW FAA RULE ON EXPENSE SHARING COMING?

The advent of terrestrial ride-sharing device apps like Uber and Lyft inevitably attracted attention to general aviation. After all, if a private automobile can be used to make a few dollars on the side, why not a private airplane? Because the FAA, that’s why not. The agency has long taken a dim view of any attempts to blur the lines it has created between private flights and those conducted with even a hint of a profit motive. As a result, long-standing FAA rules and policies allow expense sharing among members of an existing social group but do not look kindly on what it labels “holding out”: creating a new social group expressly for the purpose of a flight or flights.

That’s basically what a February 2021 report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) to Congressional aviation-policy committees said. The 28-page report, “Stakeholders Expressed Mixed Views of FAA Policies on Private Pilot Expense Sharing,” GAO-21-285, considered input from 15 organizations, including flying clubs and four companies seeking to promote expense sharing among private aircraft owners. Call it Flying Uber. For the most part, the GAO report rehashed enactment of a 2018 law requiring the FAA to develop a ride-sharing policy and how the agency complied by developing a new Advisory Circular, AC 61-142 – Sharing Aircraft Operating Expenses in Accordance with 14 CFR § 61.113 (c). The GAO report did a decent job of summarizing recent history surrounding the issue, including court cases the FAA has won and the ways it interprets various scenarios. There were two new items of interest, however.

According to the GAO report, one of them comes courtesy of the European Union where EASA—the local FAA—has explicitly allowed airborne ride sharing operations since 2012. According to the report, “EASA allows pilots to use internet applications to seek expense-sharing passengers, but only if pilots use smaller aircraft with six or fewer occupants. As of December 2020, ten companies have agreed to EASA’s regulatory terms and begun offering internet applications to match pilots with expense-sharing passengers throughout Europe.” Reportedly, one company’s platform has arranged flights for around 38,000 passengers “with no reported accidents or incidents.”

Organizations with whom the GAO spoke, including the FAA, told the watchdog agency that “Europe has a very different general aviation market and regulatory structure than the United States. For example, they said that in Europe general aviation is more expensive than in the United States because of higher fuel costs, airport fees, and air traffic control fees…. Officials noted that such differences make the European experience with expense sharing not necessarily comparable to how it could happen in the United States,” whatever that means.

The other piece of news was speculation that the FAA may enter into some kind of rulemaking. Five of the 15 stakeholder organizations the GAO interviewed “said that FAA should address this issue through a rulemaking or other formal means to define allowed expense sharing and relevant terms including ‘common carriage,’ ‘compensation,’ and ‘holding out’ in regulation as opposed to in agency legal interpretations. They said that this would provide a definitive source for pilots to reference and make the definitions easier for pilots to find, understand, and interpret when making decisions about their operations.” Some commented that if the FAA were to allow internet-based aviation ride sharing, it also could require more frequent aircraft inspections and/or more experienced pilots, which quickly starts to sound like a FAR Part 135 operation.

Proponents of internet-based aviation ride sharing clearly hope to push the FAA into a rulemaking, but that’s unlikely without additional political cover from Capitol Hill. It seems unlikely this GAO report alone comes with a large enough umbrella to make that happen.

The National Transportation Safety Board will decommission its reconstruction of TWA Flight 800 in its Ashburn, Virginia, Training Center. The Boeing 747-200 crashed into the Atlantic Ocean on July 17, 1996, shortly after taking off from the John F. Kennedy International Airport for Paris. The initial investigation into the crash focused on criminal acts, prompting the NTSB to retrieve and attempt reconstructing the shattered airframe. The accident’s probable cause eventually was determined to be an explosion of fuel vapors in the 747’s center wing fuel tank.

The reconstruction, housed in the 30,000-square-foot hangar along with other training tools at the NTSB’s Training Center, has been used in the NTSB’s accident investigation training courses for nearly 20 years. Advances in investigative techniques such as 3D scanning and drone imagery make the large-scale reconstruction less relevant, according to the NTSB. The decommissioning will occur in preparation for the end of the Board’s lease on the suburban Virginia facility. The NTSB will use those 3D scanning techniques to document the reconstruction and archive the results for historical purposes. Once documented and dismantled, the reconstructed wreckage will be destroyed.