I have something of a love-hate relationship with night flying. On one hand, I love the view of a city lit up at night, or the stars overhead, when away from ground lighting. There’s also the relatively low activity levels at airports and on ATC frequencies, the smoother air and how it’s easier to spot traffic. On the other hand, the obvious inability to spot unlighted objects is a major hindrance, as is the human eye’s poor adaptation to low-light environments. And our equipment is less-forgiving at night: lighting can fail and if a single’s engine quits beyond gliding range from a lighted landing area, risk increases dramatically.

All of these downsides have mitigations, however. If we’re worried about engine failure, for example, we can fly a twin—even if doing so increases other risks—or we can fly at altitudes and along routes that minimize the length of time we’re not able to glide to a well-lit runway. We can compensate for our eyes’ inability to see well at night by understanding these limitations and minimizing their impact. And even if we’re not instrument-rated, we can adopt various IFR procedures to help ensure we avoid terrain or obstacles we can’t see. All of these mitigations require some additional planning, however, and perhaps some extra equipment.

DARK PLANS

In my perfect world, night flights always are the subject of planning dedicated to their unique challenges. But my world isn’t perfect. For example, I’ll frequently aim to be on the ground and finished with the day’s flying well before sundown, only to have a weather delay or a late passenger shred that plan. So the first lesson of night flying is to be prepared for the lack of light at all times.

Practically speaking, this means using the preflight inspection to verify external lights are working. This is a lot easier with a passenger stationed outside to advise what happens when you flick a switch but it’s also not a demanding task to verify this on your own. If you know the plane well, noting the ammeter indications when turning on individual lights before engine start often can tell you the same thing. Verifying the operation of interior lighting—instrument-panel floodlights, avionics backlighting and individual instrument illumination—can be a bit more problematic, especially on a bright, sunlit ramp. So, before the airplane is rolled out of the hangar is a good time to check interior lighting.

Of course, your personal equipment is ready for flying at night, right? For our purposes, this means at least one flashlight—two are better, one with a red lens—along with spare batteries. Be aware that using a flashlight with a red lens will render that color invisible. Pilots who wear glasses to fly may have a pair of prescription sunglasses, but they’ll be useless at night, so be sure your untinted specs are available.

The human eye is particularly compromised in the dark, but we do have some tricks we can use to minimize the impact.

Allow time for adaptation

After darkening a room, the daylight-optimized cones concentrated in the retina’s fovea at the back of the eye remain our primary way of sensing light for the first 10 minutes or so. The rods in the retina take another 25 minutes to fully adapt.

Use Supplemental Oxygen

If oxygen is available, use it while flying at night. Without it, what the FAA calls “significant deterioration in night vision” can occur at cabin altitudes as low as 5000 feet. It helps to be in good physical condition, but by all means avoid smoking, drinking and using drugs that may be harmful, even if they’re otherwise approved.

Use Peripheral Vision

Because the concentration of rods in the retina is not as great near the fovea, best night vision is obtained by focusing away from the night blind spot depicted and concentrating on objects in your peripheral vision. Move the eyes more slowly than in the daytime.

NIGHT CROSS-COUNTRIES

If you’re instrument-rated, you may or may not be a member of the “Go Everywhere IFR Club,” but night operations are a strong argument for filing, even in good VFR. If you’re not instrument-rated, but do a lot of night cross-countries, enable the low altitude en route and IAP charting options in your EFB app or splurge for the paper copy of those charts. You don’t have to use the airways—although it’s not a bad idea—but you should pay attention to the minimum en route altitudes and the off-route obstruction clearance altitude (Oroca). The Oroca is similar to the maximum elevation figure (MEF) found on a VFR chart like a sectional but adds 1000 feet (2000 feet in mountainous areas) to the MEF’s value. You also can use the approach plates to help find the correct airport and ensure obstacle/terrain clearance.

The benefits of using IFR routes, altitudes and ATC hand-holding at night should be self-explanatory, especially if flying a single. Those benefits start by honestly assessing the airplane’s performance and comparing it to the published obstacle departure procedure (ODP), if any. And all those Notams about unlighted towers near your departure and destination airports you have to wade through during your preflight briefing? Here’s where they come in handy. By now, it should be obvious that doing night cross-countries with an IFR clearance is the way to go.

Regardless of the flight rules under which you fly at night, though, some other considerations may be important, like fuel availability along the way, plus which facilities are even open along your route. Most self-serve fuel delivery systems are designed to be available 24/7, but some airports/FBOs may lock them up at night. For that matter, some airports are locked up at night, preventing you from leaving even if you have your own car. (Don’t ask me how I know this.) The punchline is to call ahead if there’s any question about services being available en route or at your destination. In these times, it might be a good idea to call ahead anyway, just in case.

With that in mind, you may also want to rethink any personal minimums you maintain with respect to nighttime weather, like headwinds, turbulence, convective activity and icing. Headwinds can be particularly pernicious at night when there’s no open fuel pump for miles around, and icing can sneak up on you if you’re not looking at the airframe with a flashlight from time to time. Finally, a hint about convective activity and clouds in general at night: If any stars or ground lighting is visible, the darker areas are where you’ll find the clouds.

My home plate airport has runway lights, but they’re dim, making them seem farther away. And there’s no approach path indicator, much less one that’s illuminated. Coupled with the fact there is very little ground lighting surrounding the runway, a night landing there is a great example of the so-called “black-hole” approach. Basically, the lack of light other than the runway itself minimizes one’s ability to use peripheral vision to perceive depth, or how high we are above the runway.

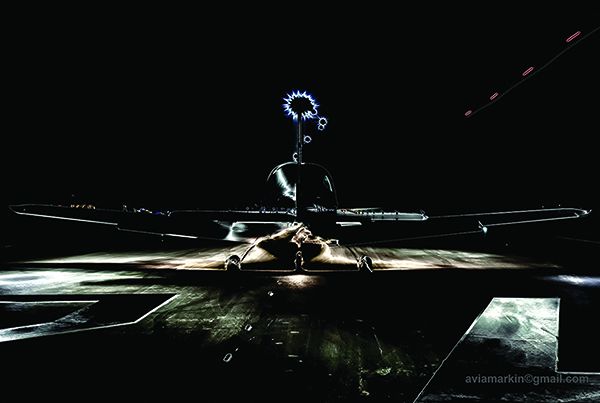

My solution is to perform what some might call an “aircraft carrier” approach. I fly a longer downwind leg, which sets up a longer final. Once on final and aligned with the runway, checklists complete, gear and full flaps down, I slow to about 70 knots while maintaining altitude. This requires pitching the nose higher than a normal approach and puts me slightly behind the power curve. But it also places the airplane in an attitude similar to the landing flare. I fly that attitude down to the runway, using power as the primary way to control the descent, and touch down on the mains with the nosewheel off the ground. The lack of depth perception often means the touchdown’s timing is a surprise.

NIGHT AT THE AIRPORT

At some point on your night flight, you’ll need to use an airport. During your preflight, you determined your landing/taxi light(s) are working, so don’t get hung up on which to use at night. There’s no such thing as too much light during nighttime ground operations.

Of course, the navigation lights and any rotating beacon should be illuminated once the engine(s) is/are running and, by convention, a taxi/landing light used when in motion. Please be mindful of where you’re pointing your landing/taxi lights on the ground, by the way—it’s easy to ruin someone else’s night vision. If you have a so-called “logo” light illuminating the tail, consider using it and other lights when crossing a runway. I turn on every light on the plane for takeoff and landing, day or night. Your plan may vary. The AIM has a good discussion of how to use your aircraft’s lighting at night at paragraph 4-3-23, Use of Aircraft Lights.

Depending on the airport, finding your way from the ramp to the departure runway might be an adventure. Smaller airports may lack a published airport diagram, for example, or have little to no parking ramp/taxiway lighting, along with poor or faded pavement markings. At non-towered facilities, it’s always a good idea to know how the surface lighting system works, and on which frequency. It’s usually the Unicom/CTAF at smaller fields, but those with part-time control towers typically will default to the CTAF/tower frequency and not Unicom when the tower’s closed. This information is in the Chart Supplement (formerly the A/FD) entry for the airport and details which lighting systems, including approach lighting, are on the pilot-controlled lighting (PCL) circuit.

When the tower’s open, feel free to ask controllers to turn up or down the runway lights, including approach lighting systems and the sequential strobe (rabbit), as needed. In our experience, changing lighting intensity via the PCL capability at a typical non-towered facility may be a matter of luck. When PCL was first put into operation, three clicks got you low intensity, with a medium step at five clicks and high intensity at seven. These days, it seems medium is the standard setting and using PCL to change it up or down doesn’t work. It could be the airports I’ve been using; you may be able to get all three intensity settings where you are.

A final word about lighting: Pay attention to any visual approach slope indicators (VASI, PAPI, etc). There’s a reason they exist and pilots ignore them at their peril, especially at night.

Flying at night is a lot like flying in the daytime—it’s just that you can’t see everything. And sometimes you can’t be sure what you’re seeing is what’s really there, thanks to optical illusions that crop up at night.

Autokinesis

Autokinesis is when something stationary appears to move. It’s caused by staring at a single point of light against a dark background for more than a few seconds: The light appears to move on its own after eight to 10 seconds.

To counter autokinesis, focus the eyes on objects at varying distances and avoid fixating on one source of light. Also, increase your visual scan rate, and concentrate on lighted objects outside of the nighttime blind spot. Don’t stare at a single light for more than 10 seconds.

False Horizons

A false horizon can replace the natural one on dark nights, in part by confusing ground lighting with stars in the sky. Mountainous areas can be particularly hazardous when the natural horizon is obscured by uneven shapes, and the abrupt demarcation a shoreline presents can be very confusing.

Color Perception

The daylight-optimized cones in your eye’s retina? Turns out they’re also the part of the eye most sensitive to color. At night, when we primarily use the rods, our ability to perceive color is drastically reduced, with many of our perceptions based on variations in light and/or its absence instead of color.

SHEDDING LIGHT

At any given time, half of our day doesn’t involve sunlight at all. Failing to understand the limitations night flying imposes can effectively mean there’s a large portion of time when you can’t (or maybe shouldn’t) fly. One of the real challenges of night flying is understanding that the airplane doesn’t know or care that it’s dark, while behaving as you would in the daytime is a poor response to the challenge.

The problem with night flying isn’t the airplane; it’s the pilot. We can’t see as well at night, and what we do see often is compromised. So we have to take steps to mitigate the additional risks by paying extra attention to our flight planning, our equipment and ground operations.

Jeb Burnside is this magazine’s editor-in-chief. He’s an airline transport pilot who owns a Beechcraft Debonair, plus the expensive halof of an Aeronca 7CCM Champ.