After reading Tom Turner’s excellent article on non-precision approaches (“Non-Precision Stability,” January 2021), I’d like to add a couple of comments as a “legacy dive and driver” (instrument-rated in 1961).

First of all, the Instrument Flying Handbook talks about the benefits of stable descent for swept-wing jet aircraft, and they do exist; I flew them for 35 years. However, I suspect the majority of your readers are flying light singles and twins, which don’t have adverse aileron effects at low speed and are far more responsive in that regime. For that majority, I think that while being the mark of a competent airman and always desirable, the true stabilized flight concept is overstated.

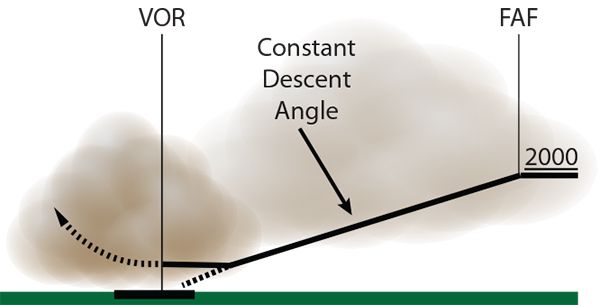

As Tom points out (my interpretation), there is no “one size fits all” in many aspects of aviation. Using the dive-and-drive concept does require good judgment as to how steeply one dives (I strongly dislike that term and would prefer descend) and how far from the runway he wants to be at MDA. The idea is to acquire the runway environment prior to reaching the MAP. One must then avoid what seems to be a frequent response of “pushing over” and diving for the runway. I have observed this reaction many times during my 61 years of flying by both airline and GA pilots.

Finally, Tom reinforces his point about a process which requires mental calculations during a phase of flight in which the single pilot may already be close to the task saturation point by making an arithmetical error himself while writing his article! “3000 feet to 1780 feet, 1120 feet in total.” It should be 1220 feet! So ask yourself, if the highly respected Tom Turner can make this error while sitting comfortably at his computer, are you capable of such challenges in the clouds, perhaps with turbulence, and radio chatter? So, I submit that lacking an advisory glide path, there are situations where good old dive and drive offers some advantages.

Jim Piper – Via email

Tom might have made that error in his original manuscript, but we allowed it to get through editing and into print, so we’re just as guilty.

MORE SELF-ANNOUNCING

Regarding your “Hear Me Out” article, Mr. Hartmaier’s opposition to your personal view that the N-number is unnecessary at uncontrolled fields and your follow-on response, I would like to add a couple of perspectives further supporting the importance of including the N-number.

First, at a local non-towered airport, I personally experienced a transmission from another aircraft stating he “was three miles east of the airport inbound.” He included his N-number and, thanks to ADS-B, I easily recognized by his N-number that he was in fact west of the airport, as was I. His N-number reporting aided in identifying his position error, which we were able to sort out and ensure safe operations.

Second, there are six flight schools, including two university schools, within a 30-mile radius of that airport, so there are often multiple aircraft of the same type in the pattern. While the university aircraft have similar N-numbers, those specific identifiers are very helpful in determining precise situational awareness (thanks to ADS-B), especially when two of those aircraft are in similar areas of the airspace.

Finally, your assertion that “it takes time to include the N-number in the transmission” is overstated. My N-number is seven syllables in length and takes all of 0.8 to 1.0 second to transmit. Most N-numbers I see would also require about a second to transmit—hardly a significant impact on frequency traffic given the additional situational awareness/safety it provides.

You may continue to disagree with Mr. Hartmaier and me, but I will much prefer pilots who include their N-number because it adds to safety and situational awareness.

Eric Boelzner – Via email

EVEN MORE

Your response to Bob Hartmaier was spot-on. The Advisory Circular he references is not the best the FAA has to offer and could use another revision more in line with your view (which I share). More emphasis on brevity would be nice as well as information most useful to other traffic.

Rae Willis – Via email

STILL MOAR!

Let’s start by saying, at least in South Florida, most if not all airplanes are ADS-B Out equipped. Suggesting that not all aircraft have that capability is not a valid reason for not using the N-number when self-announcing. Many airplanes have ADS-B In traffic capability, whether panel-mounted or on portable screens.

I agree that, in the pattern, we need to be looking for traffic and not pawing at an iPad. Saying the N-number in the crosswind, downwind and all the way around is not necessary. Clogs up the airwaves. Is “Cessna 12345” more cumbersome than “white and blue Cessna? “ (Maybe only use the last three digits/letters of the tail number?)

But approaching or departing non-towered airports, things are different. Reporting “10 miles north” is not sufficient. (10 miles is the recommended distance for initial blind transmission.) Granted, most likely there may not be an imminent danger of collision, but with the N-number, I can immediately identify the airplane with ADS-B traffic way before I have visual contact.

ATC traffic advisories are usually given in relation to an airplane’s track: “traffic at three o’clock.” Self-announcing “five miles north” needs a bit of interpretation. What is missing, besides the altitude, is the airplane’s flight direction. We cannot always assume it is “direct to the airport.” Knowing that N12345 is a Cessna 500 feet above my altitude makes it easier to visually identify the “Cessna.” It is less ambiguous especially if there are multiple airplanes “north of the field” which may or may not be flying to the non-towered airport.

I know ADS-B traffic is “just” for awareness, not traffic maneuvering as would be the case with TCAS resolution advisories. But now that I know which airplane on the screen is N12345, I can visually be on the lookout for that Cessna in the right direction and altitude—above or below me. Separately, with the necessary equipment, Garmin’s relative motion traffic vector adds to situational awareness because it takes into account the ownship’s future track and the traffic.

However, in the spirit of Monty Python, I will argue something completely different. First, you will not see a regulatory reference that requires announcing the N-number. That is settled. But there are three sources that are non-regulatory stating the same thing: AIM 4-1-9, AC 90-66B Chg 1, and an AOPA Safety Advisor pamphlet—similar to other “best practices.”

Here is the clincher: I would probably agree with you if it were pre-2015, when not many airplanes were equipped with ADS-B Out. Not the case today. So why would we want to give up the safety benefits of current technology?

Now, if you want to talk about communications during instrument approach practice at non-towered airports, that is another story altogether!

Luca F. Bencini-Tibo – Weston, Fla.

At non-towered airports such as mine in Watsonville, CA (KWVI) the more crowded the airport environment the more important it is to be clear as to where and who you are and what you are going to do. While appreciating the discipline to not hog the airway I think this is the more important factor. When there is no one else around, if you could be sure of that, there would be no need to say anything even though you could own the airwaves.

And please speak clearly. Also, slowly enough to be accurately heard. Enunciate! blahburgcezna12349straightinfortwennyfour – – – this is NOT communication!

Mr’s McNew and Burns offer good insights. Communication is only COMMUNICATION if the speaker is both heard, AND understood. Enunciation is not just a 5 syllable word. It’s a major factor in conveying flight critical information.

HOWEVER, in today’s aviating environment it is impossible to know if “… there is no one else around…” The list of ADSB-OUT exempted aircraft is long. Many of these ADSB-IN invisible aircraft have no electrical systems nor any operating radios. What??? No electrical system??? That group of aircraft includes flying parachutes (both motorized and not), balloons, antique aircraft, some EAB aircraft, powered aircraft that fly outside of Class B, C, Class E above 10,000′ (some execptions) or a chunk Gulf airspace, and powered aircraft with dead batteries. FWIW, I’ve had two dead battery events … one with a relatively new Gill that developed a bad cell, and one when my perfectly good battery died because my alternator crapped out on a long cross country.

It’s sad, but true that some of us (me included) can hear – but not process a complex and rapid fire transmission that includes

>>WHO (N number and aircraft type),

>>WHAT (wachagonnado),

>>WHERE (distance from a known point – i.e. airport -, direction from said known point, ALTITUDE, and whether descending or climbing)