As a result of its ongoing investigation into the fatal June 21, 2019, crash of a Beech A90 King Air after takeoff from a Hawaiian parachute operation, the NTSB is issuing three recommendations to the FAA calling for increased oversight of flight instructors, especially those CFIs with “substandard student pass rates.” According to the NTSB, the “accident pilot had failed three initial flight tests…after receiving instruction from a single instructor.”

After each failure, the accident pilot subsequently passed his flight tests but “the pass rate for other students taught by the same flight instructor was 59 percent (for the two-year period ending in April 2020).” The NTSB noted, “FAA data show the average national pass rate for students of all flight instructors is 80 percent.”

The FAA’s stated practices on flight instructor surveillance are that “substandard pass rates are indicative of instruction that needs to be more closely monitored so the FAA inspector can determine whether the instructor is providing adequate flight training,” the NTSB said in a statement. But the Safety Board found the accident pilot’s flight instructor was not receiving the appropriate additional scrutiny. The NTSB asked the FAA to develop a system to automatically alert its inspectors of flight instructors whose student pass rates fall below 80 percent.

The FAA already has a tracking system designed to monitor such statistics among instructors but there isn’t an automated method of notifying an FAA inspector when a pass rate falls below the FAA-established rate of 80 percent. As a result, the NTSB asked the FAA “to include substandard student pass rates as one of the criteria necessitating additional surveillance of a flight instructor.” The NTSB also recommended that, “until a system that generates an automatic notification of flight instructor substandard pass rates is implemented, FAA inspectors should review flight instructors’ pass rates on an ongoing basis to identify any in need of closer monitoring.”

According to the NTSB’s investigation into the Hawaiian crash, which killed all 11 on board, the accident pilot had logged some 53 hours of dual instruction in another King Air flown by his instructor. The accident pilot had a total of “4.6 hours as a student pilot when he began logging (and the instructor began endorsing) commercial pilot training and experience,” the NTSB said. It added that the flights were “most likely conducted by the flight instructor with the accident pilot sitting in the copilot seat.”

In addition to automated alerts when a substandard instructor is identified and using student pass rates as a criterion for additional scrutiny, the NTSB’s safety recommendations, A-20-040 through A-20-042, requested that the FAA apply its existing surveillance to instructors meeting the revised criteria.

Our May 2020 issue included an article about ATC facility closures during the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic, titled “ATC-Zero.” At that time, several FAA ATC facilities where the virus was identified had temporarily closed for cleaning or other purposes. The closures generally lasted a matter of hours, with some extending for a day or two. On January 20, however, Florida’s St Pete-Clearwater International Airport (KPIE) declared an ATC Zero event starting immediately and lasting until February 1, the longest of which we’re aware.

A January 22, 2021, Letter to Airmen (LTA-PIE-6, pictured at right) noted, “IFR services will be provided by Tampa Approach Control and as with other uncontrolled Airports, clearances and releases will have to be obtained through telephone communications. Please do not forget to CANCEL, this is a ‘one in’ ‘one out’ procedure.” Local media reported the FAA said “staff exposure” was the reason for the closure’s extended duration, which to us sounds a lot like the majority of the ATCT staff tested positive and are in quarantine for two weeks.

Check Notams, and carry plenty of gas. —JB

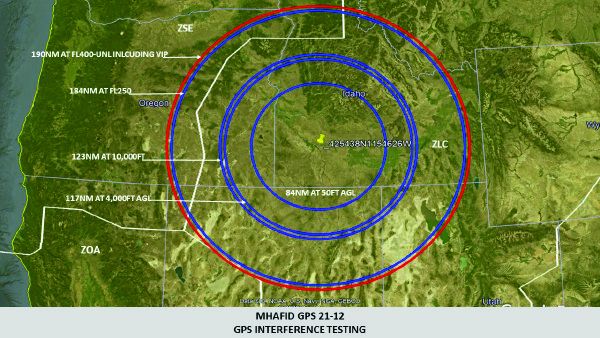

GPS INTERFERENCE TESTING DISRUPT MORE OPERATIONS

You’ve probably seen the Notams advertising GPS interference testing by the U.S. military, which “may result in unreliable or unavailable GPS signal.” They’ve been around for several years and usually aren’t a problem. Recently, however, the number of related reports submitted to NASA’s Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS) have increased, according to IEEE Spectrum, a monthly magazine published by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers.

And, acording to the magazine, which obtained “internal FAA materials,” the data just for the Los Angeles Air Route Traffic Control Center “includes 173 instances of lost or intermittent GPS during a six-month period of 2017 and another 60 over two months in early 2018.” The magazine acknowledges the FAA reports “are less detailed than those in the ASRS database, but they show aircraft flying off course, accidentally entering military airspace, being unable to maneuver, and losing their ability to navigate when close to other aircraft.”

The military issues Notams, like the one highlighted on the opposite page, to advise operators of the testing, but, “Most pilots who fly through affected areas experience no ill effects, causing some to simply ignore such warnings in the future,” the magazine said. Our experience is similar, having operated in related airspace on several occasions, to no ill effect.

But a Radio Technical Commission for Aeronautics group looking into GPS interference “found that the number of military GPS tests had almost tripled from 2012 to 2017” and that there was a “tenfold” increase in related ASRS reports from 2018 to 2019. The increase comes at a time when GPS by far is the predominant position-finding technology used in the FAA’s NextGen navigation and surveillance system, portions of which the agency mandated beginning in January 2020.

The magazine noted that complete loss of GPS signal isn’t the only outcome of the testing: The military’s activities also can convince avionics that the aircraft is in a position different from the one presented. According to the magazine, “The ASRS database contains many accounts of pilots belatedly realizing that GPS-enabled autopilots had taken them many kilometers in the wrong direction.”

As the FAA’s GPS interference Notams state, “Pilots are encouraged to report anomalies in accordance with the Aeronautical Information Manual” and we encourage you to frequently check related Notams, which are supposed to be published at least 24 hours in advance.