One pilot’s romantic ideal of flying might be the soft, sighing touchdown of a taildragger on freshly mowed grass at the end of a warm summer day. Another’s could involve a floatplane splashing down next to a favorite Alaskan fishing hole, or a sailplane working the thermals. No matter which of these might be your ideal, they all require warm weather, which is kind of hard to find right now in the Northern Hemisphere. Frozen fields, ice, snow and low overcasts may be the norm where you are, robbing us all of favorite destinations and leaving behind gray, overcast days and dark nights, perhaps laden with frozen precipitation.

That said, winter flying can offer many pleasures. Among them are floating over a snow-covered landscape, weekend trips to your favorite ski venue, or trading floats for skis and doing some ice fishing. Putting aside the operational challenges winter weather can bring, there are many other practical demands it may pose to our flying. With that in mind, we offer up some tips that can help make committing aviation during the winter more practical and enjoyable.

CLOTHING/WINTER GEAR

One of the most important involves keeping the humans safe and warm in winter weather. As anyone who’s flown a piston single in winter will know, their cabin heating systems can leave much to be desired. Piston twins equipped with gasoline-fired cabin heaters usually don’t have this constraint—even as those heaters can be cantankerous and expensive to maintain—while turbine aircraft typically have much more reliable and efficient environmental systems. We’ll get to ensuring those heating systems are working as well as they can in a moment, but we need to think about keeping you and your passengers comfy when cruising at altitude in freezing temperatures.

The basic answer to staying warm in winter is having plenty of warm clothing and winter gear. Just as you might layer garments when outside in cold weather, it’s always a good idea to have more textile products available than fewer. A blanket or two in the cabin also is a good idea, especially for the back seats, which in some airplanes can be drafty and relatively unheated by the time warm air flows back from the engine compartment. In addition to you and your passengers remaining comfortable, there are a couple of safety-related reasons to plan ahead and carry winter clothing and gear.

The first is to ensure the pilot—you—can properly perform his or her duties. Just as your engine has an optimum operating temperature range, so do you. According to Medical Aspects of Harsh Environments, Vol 1, part of the Textbook of Military Medicine, a multi-volume publication of the U.S. Army and the Office of the Surgeon General, “On computerized tracking tests completed during mild cold exposure, recent work has demonstrated significant increases in the number of errors, the speed of incorrect responses, and the number of false alarms. These effects [were] obtained when tests were constructed that required continuous rapid, accurate responding, with minimal opportunity available to inhibit error responses,” like flying.

A second reason to carry adequate cold-weather gear arises when considering an off-airport landing or even a precautionary diversion to the nearest runway, which may be at an unattended airport. Alaska’s state law requires intrastate flights to carry various survival equipment at all times and adds snowshoes, a sleeping bag and a wool blanket for each aircraft occupant over four years of age during the winter. While snowshoes might be excessive in the Lower 48, warm boots aren’t and a couple of sleeping bags might come in handy if you are forced to spend the night in your plane.

Thoroughly preheating an aircraft engine should be thought of as an endurance race, not a sprint. Ensuring a several-hundred pound mass of metal alloys and thick oil is warm enough to minimize wear on startup is something best done over time. Which argues strongly in favor of an overnight in a heated hangar.

If that’s not in the cards, an installed heating kit from Reiff or Tanis might be the next best thing. Those kits mount electric heating elements to the oil pan and cylinder bases, and are always available once installed. Just plug in an extension cord and the engine slowly starts warming. Again, an overnight is best.

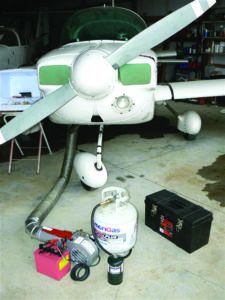

Next in order of desirability is a propane-fired heater like the one pictured at right. With them, care must be taken to ensure some components—like hoses and fiberglass cowlings—don’t get too hot, so they’re not a plug-in-and-forget proposition. In addition to a propane tank, most also need electricity to power a blower, which can be problematic on a remote tiedown or too cumbersome to take with you.

Some old-timers swear by a 100-watt light bulb (LEDs need not apply) in a trouble light stuck under the oil pan and—again—left overnight.

Except for the heated hangar, all of these methods work best when cowling inlets are plugged and cowl flaps closed to retain heat. An old blanket thrown over the cowling also is recommended.

PREHEAT/PREFLIGHT

Being warm and healthy is just as important for the aircraft as for its occupants. The process begins with preheating at least the engine before starting it and ensuring any melted ice or snow doesn’t flow into the airframe where it can re-freeze at altitude and cause problems. The gold standard of preheating an aircraft is to put it in a heated hangar at least overnight. The sidebar above details some preheating do’s and don’ts we recommend.

One question that often arises in cold weather is when the engine needs to be preheated. Lycoming says “preheat should be applied anytime temperatures are at 10˚ F or lower” and that “76 series models” like the O-320-H and the O/LO-360-E “should be preheated when temperatures are below 20˚ F.” The engine maker notes that “failure to preheat the entire engine and oil supply system as recommended may result in minor amounts of abnormal wear to internal engine parts, and eventually to reduced engine performance and shortened TBO time.” Continental simply says, “Preheating is required whenever the engine has been exposed to temperatures at or below 20° Fahrenheit/-7 degrees Centigrade (wind chill factor) for a period of two hours or more.” We like to err on the side of caution and require a thoroughly preheated engine at or below 40 degrees F.

Equally important is ensuring there’s no water in your fuel that can freeze at altitude, perhaps clogging strainers and selectors. Crankcase breathing tubes also should get closer attention in cold weather since a blockage can pressurize the engine and force oil overboard.

It’s also important to understand that cold weather affects every aircraft system, even the control cables. Batteries have less power for starting, hydraulic systems can spring leaks as different materials shrink at different rates and constant-speed/feathering propellers may be balky until warm oil can circulate in their hubs.

According to Cessna’s Pilot’s Operating Handbook for the 1977 182Q Skylane, “Rough engine operation in cold weather can be caused by a combination of an inherently leaner mixture due to the dense air and poor vaporization and distribution of the fuel-air mixture to the cylinders.” The POH notes these “conditions are especially noticeable during operation on one magneto in ground checks.”

Cessna recommends “the appropriate use of carburetor heat” and notes that full carb heat may be required below -12 degrees C, “whereas partial heat could be used” between -12º C and four degrees C. The POH urges using the minimum heat required for smooth operation in takeoff, climb and cruise.

Cessna notes that care should be exercised when using partial carburetor heat. “Partial heat may raise the carburetor air temperature to 0 to 21º C range where icing is critical under certain atmospheric conditions.” Cessna recommends using a carburetor air temperature gauge and maintaining temperatures “at or slightly above” its yellow arc. At right is the carb heat box used on a Lycoming O-360 installed in a 172M Skyhawk.

WINTERIZE THE AIRPLANE

Which raises the question of how you can winterize your aircraft to help prepare it for the cold weather. The place to start is with manufacturer’s guidance and the material in your POH/AFM. For example, there may be a winterization plate or two the manufacturer recommends be installed to partially block an engine’s oil cooler from working too well—warm oil flows much more easily than cold. But the typical POH/AFM offers little advice beyond preheating the engine.

It goes without saying that the airframe must be free of any ice, snow or frost, even minuscule amounts of which can disrupt airfoils (wings, tail surfaces and propellers). It also may be a good idea to block cabin air inlets to help prevent drafts and inspect/repair cabin and baggage door seals.

Worthy of extra attention is the cabin heat system itself. Piston singles typically employ a shroud or “muff” routing ambient air past one or more exhaust pipes to extract heat energy and then pipes this “heated” air into the cabin. Ironically, this is what you would do if you wanted to efficiently route carbon monoxide to you and your passengers. For this reason, detailed examination of exhaust and cabin heat systems is always appropriate during scheduled inspections but never more so than in winter.

That same heat-extraction method often is used for an engine’s carburetor heat system, which some manufacturers suggest can help remedy vaporization and distribution of the fuel-air mixture in cold weather. See the sidebar on the opposite page for details.

Finally, if you’re lucky enough to be flying something with ice protection, obviously ensure the system—electrical, pneumatic and/or fluid-based—is working well and that it becomes a major part of your preflight in cold weather.

At some point in your flying career, you’ll likely be confronted with a snow-covered airplane you want to fly. You probably won’t have access to a deicing truck, so you’ll need to completely clean off all the frozen water the old-fashioned way.

The problem is an aircraft’s exterior surfaces can be delicate and, especially, may not react well to some fluids that might be available, like undiluted alcohol. Cessna says a “50-50 solution of isopropyl alcohol and water will satisfactorily remove ice accumulations without harming the paint” on its 1977 182Q Skylane, so be sure to consult the manufacturer’s data before using any deicing chemicals, especially on the windows.

Start with a broom and gently sweep off the loose stuff, being extra careful around antennas, lights, fuel vents, control surfaces and pitot tubes. Sometimes frozen precipitation will stick to the surface. Whatever you do, scraping it off can damage the paint or underlying structure. Instead, use a gloved hand to loosen it and brush it off. Be sure to check openings like the propeller spinner and where control surfaces are hinged for packed snow or ice that can affect a component’s balance. Cabin and wing covers can make a lot of this academic, even if they’re cumbersome to haul around and install/uninstall.

CALL AHEAD

If you’re unsure of what to expect at your winter destination, want special handling like a heated hangar or just need to verify TKS deicing fluid is available, it pays to call ahead. In our experience, FBOs can be uneven in their zeal to meet your preheat needs, even if they’re as simple as running a drop cord out to your tiedown. It helps, of course, if you bring your own extension cord, cowling plugs and engine cover.

When you call, ask about runway and taxiway condition. Extreme conditions at an airport with airline service or a large number of non-scheduled operations likely will warrant braking-action reports, or a Notam for closed surfaces and buried runway lights. However, that’s not necessarily the case at smaller facilities. There, it’s not uncommon for the line person to also run the snowplow as well as the coffee machine. That presumes the airport even has its own snowplow; smaller airports may depend on the county’s highway department, which likely won’t have runways, taxiways and ramps at the top of their priorities.

Landing on a snow-covered, long-enough runway in good-weather conditions might not be too much of a challenge, but trying to get down and stopped on 3000 feet of snow and ice in a stiff crosswind demands greater caution. It’s useful to know runway conditions at your destination before you show up without enough fuel to divert to uncontaminated pavement; sometimes a phone call or two is the only way to be sure.

GIVE PIREPS

Winter weather can be both dynamic and unforgiving even as its denser air helps engine and airfoil performance. It goes without saying that you’ll obtain and understand a full preflight briefing, paying special attention to icing-related forecasts and pilot reports. But try to think also about giving pilot reports, even if what you see was in the forecast. Doing so will help someone else make an informed decision and always adds fidelity to the big picture conscientious pilots seek before a flight. And if your destination airport’s conditions include unplowed surfaces, that’s certainly worth phoning in.

Safe and comfortable winter flying is about more than airframe icing or digging out your airplane after a snowfall. Do your homework and perform necessary preventive measures, like checking exhaust systems and door seals. Plan well ahead and take extra time for your preflight. Remember that winter weather can be unpredictable—the ability to launch on your cross-country flight a day earlier than planned can come in handy. The good news is this cold stuff will be gone in a few more weeks, and then we can get back to flying taildraggers off grass runways.