Thinking back to my traditional aviation weather courses, I realized they didn’t address intense wind events where the agency of high wind all by itself wreaks its own special form of havoc. This year there were numerous high wind events — several haboobs in Arizona, a derecho in the Midwest, and wind-driven fires in California, Oregon, Colorado and then California again. There were also unusual wind storms that caused major dust storms, flipped airplanes and uprooted trees in Washington, Idaho and Utah. They destroyed billions of dollars in property.

Anomalous and novel wind events happen, but extreme wind events induced by the added energy from a warming atmosphere are beginning to seem like the new normal. Whether or not you agree with that view, you would probably agree that wind storms demand their own risk management considerations.

WINDSHEAR

A major wind event can occur at ground level and aloft, probably blowing in different directions—thanks at least in part to the Coriolis effect—with shear zones between abrupt wind direction changes. But even if the forecast or weather report doesn’t explicitly advertise windshear, count on encountering it in a windstorm.

The worst place to encounter windshear is near the runway. On an approach during a wind event, one sign you might be in for low-level windshear is when your crab angle on final approach is exaggerated or perhaps out of sync with the reported surface wind. Glass cockpits or your trusty EFB may display in real time the winds you are experiencing. When your reported or calculated wind direction is significantly different from the reported wind speed and direction on the ground, plan on encountering some windshear.

You are particularly vulnerable during departures, a time when there are several constraints. You are at full power with no reserves to tap into if you encounter an overwhelming downdraft, at a higher angle of attack and slower speed while in proximity to the ground and obstructions and will be at your highest trip weight, which saps climb rate performance. This is not the time you want to encounter a violent downdraft or a side gust pushing you off the center line and toward obstructions. Departures into high wind conditions require your focus and your A game. Remember your training.

When confronting crosswinds during landing or takeoff, the first things to consider are wind direction and runway orientation. The airplanes most of us fly have a maximum demonstrated crosswind component, which basically reflects the effectiveness of the rudder demonstrated during flight testing. Others may have hard limits above which it’s illegal to operate.

For any given airframe, there is a point where the amount of crosswind is more than the rudder can counteract. “At landing speeds, the airplane will not be able to hold the centerline and will drift downwind, risking loss of control. There are a few cheats to overcome crosswinds, like landing a bit faster (if runway length isn’t an issue) and sticking the landing quickly before deceleration and lack of airflow saps rudder authority. Multi-engine pilots have the option to use differential power.

No matter what techniques you use in a strong crosswind, every pilot should know the airplane’s crosswind limits and not fudge any personal minimums representing a no-go.

TURBULENCE

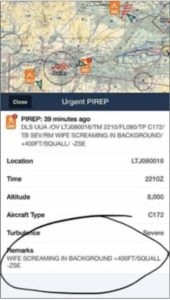

Turbulence often accompanies high-wind events. If you see a Notam for regional turbulence, the cause is often a shear zone where wind directions and speeds vary significantly at different altitudes.

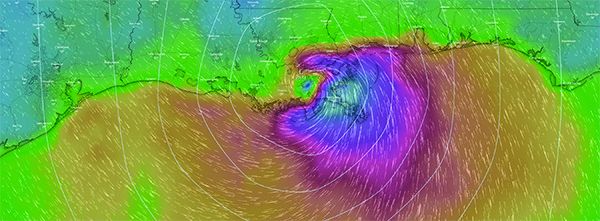

While a pilot can just take the Airmet for turbulence as notice the flight will be uncomfortable and items will need to be secured, you should look into the underlying reasons. An investigation using online resources like Windy.com to identify and visualize winds at different levels and how the locations of ridges, troughs, highs, lows, channeling terrain and the height of the jet stream might allow you to identify the zones where the winds aloft have consistent rather than shifting directions. Based on that, I frequently choose to cross both terrain-related venturi effects and areas with particularly strong winds aloft in a direction perpendicular to the wind. This allows me to get through the zone of conflict as quickly as possible. I also look for a series of altitudes where flow directions and speed are relatively aligned. Altitudes near shear zones—abrupt changes in wind direction and speed—should be avoided.

Again, the risk management tip for forecast turbulence is to bring your A game. You will better understand your options in the air if you did your homework about the weather on the ground. You’ll also need to know your maneuvering speed (VA), and how slowing down to at or below that speed might affect your fuel consumption, endurance and exposure to wind vectors, which may amplify inefficiency. It should go without saying that an encounter with in-flight turbulence is an inopportune time to realize you haven’t slowed down, or that your oxygen bottle isn’t strapped down, or you don’t have enough fuel for the solid-gold alternate that’s too far upwind.

WAVES

The discussion about encounters with waves tends to bias toward “big mountain range” phenomena. It’s true that the most dangerous encounters with mountain waves are in places where massive ranges are high enough to poke into undisturbed and faster wind flow, like the Sierras, Cascades or the front range of the Rocky Mountains. When the orientation of the mountain range, the wind direction and speed hit a certain magical resonance, a mountain wave appears.

However, mountain waves also are common on a regional basis and can be induced by a single smaller range or ridgeline. There are several areas on the Snake River Plain and near Salt Lake City where I have encountered mini-waves that got my attention.

The telltale in-flight sign of a wave encounter is a sinusoidal need to push and pull the yoke to maintain altitude. If you do that, pretty soon your airspeed will be sinusoidal too. The bigger the variation, the stronger the wave. If the wave is particularly strong, you will not be able to comfortably hold an altitude because it will push you from near stall speed to VNO on each peak and trough transition.

If and when this happens, it is a good time to abandon altitude holds and configure the airplane to fly at or below its maneuvering speed. Based on your pre-flight study of the weather systems and wind patterns at various altitudes, you should have a sense of which direction will have better or safer prospects. Now is a good time to vector yourself away from the higher terrain and look out for any rotor clouds waiting to ruin your day. A perpendicular vector will help you escape laterally, versus just getting carried downstream by the potentially violent current.

Ground handling is one wind consideration that is frequently overlooked or underestimated. You might be able to handle landing in a 60-knot wind coming straight down the runway, but can you make a perpendicular turn to a taxiway without crabbing? You might find your plane wanting to jump back into the air since the wind speed might be close to liftoff speed, but brakes aren’t much good when your plane is partially airborne. And they don’t work well on icy surfaces. Winter winds with ice and snow berms is a topic all its own. The likelihood for strong winds to lift a wing means this is not the time to forget the elevator and aileron orientations for crosswinds on the ground.

In super windy conditions, you may also need ground crew assistance to tie down your airplane. Any time you have to be actively managing the controls while at a full stop, it is often hard to get out of the plane without an assistant. Many full-service FBOs in windy locations are prepared to assist light or tailwheel aircraft that particularly suffer when tiedowns are oriented in a way that makes them a challenge in a wind.

Even if conditions are calm when you land, it’s important to secure your plane so it can handle a major wind event while you are away. Point the plane into the wind and/or the anticipated wind changes, with brakes on, wheels chocked, if possible, and tie down straps or chains placed securely enough to prevent on-ground jostling from buffeting winds. Use control locks or secure the yoke with a strap or belt.

I can’t tell you how often I have taxied past tiedown areas at various airports and seen one or two poorly secured aircraft waving at me, wings a-rocking, rudders and stabilizers flapping up and down and side to side like an overly enthusiastic child. I could only groan and imagine the damage and wear it was causing.

RIDGES AND OBSTRUCTIONS

High winds will interact with ridgelines and ground obstructions to create rotors—air rotating around an axis parallel to the “obstruction. Always cross a ridge “strong,” meaning with enough clearance and available horsepower to counteract downdrafts. Crossing a ridge while still climbing puts you in a “weak” position and requires particular care. If you are barely climbing and at VX, you are in no shape to cross a ridge in high wind conditions. Circle for more altitude and cross the ridge with strength, with a good climb rate or level with some excess horsepower available. When crossing a ridge for descent, it is particularly important to stay below maneuvering speed. Encountering a rotor on the backside of a ridge in the yellow arc is not recommended.

In the airport environment, either on approach or in the pattern, you need to be on alert for how obstacles near the runway might affect local winds near the touchdown zone. Lines of trees or hangars can create some seriously nasty rotor currents near the ground during high winds. I remember a particularly rough arrival at a small Texas airport. As I was slammed to the runway, I could see the wind responsible for that nasty rotor hit a line of trees and hangars perpendicular to the runway. The rotor from the crosswind perfectly aligned as a vector to the obstacles.

When there is a strong crosswind, note the orientation of obstructions that may create extra drama near your planned touch-down zone. You might be able to mentally visualize the rollers and waves from wind tumbling over the trees and hangars. Your mental images can help you adjust your aiming point to avoid the encounter by landing short or long. Either way, be ready for a go-around.

DUST AND SMOKE

I had the “opportunity” to navigate through a major wind event this fall as I flew from Salmon, Idaho, to Seattle, Washington. The winds aloft forecast showed the system building through the afternoon, which meant potential no-go conditions for crossing the Cascades later in the day. Since my preference is always less risk, I chose a northern path to stay clear of the severe turbulence Airmet and a fire TFR, and timed my departure so I would cross the frontal boundary over the Columbia River basin. Encountering turbulence over a plain rather than a mountain range is much less drama.

On departure, this particular wind storm was actually a slight tailwind aloft for me, but it evolved into a wind on the ground that was perpendicular to my flight path as winds aloft remained relatively calm. I could see the dust storms at ground level building downwind of my left wing. This ground-level dust storm effectively eliminated landing at airports that would be the easiest to glide to. A storm that eliminates your downwind options, the ones you will be blown toward if you lose power, should get your attention because those options are effectively walled off. When that happens, it’s a good idea to divert further upwind so you have more options and time.

As my flight progressed, wind speeds on the ground were between 35 to 55 knots and the airports downwind suffered increasingly lower visibilities. The wall of dust that built off my left wing eventually merged with a separate wall of smoke from local and California fires, resulting in unforecast IMC at airports south of my route. Those airports were also surrounded by fire TFRs. So regardless of them being IMC, from a ground-handling perspective, they were unlandable for anyone with the sense that God gave a chicken.

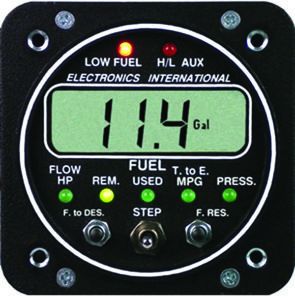

Fortunately, within 10 minutes of these conditions emerging beneath me, I reached the other side of the Cascades. No drama. On the west side, the wind was not an issue and the winds aloft remained relatively mild. I paid for my wind mitigation path diversion with some of my personal fuel reserves, landing with the required 30 minutes of fuel remaining when I prefer to always have a strong hour in reserve. That’s what extra fuel reserves are for: buying better options.

Another complex risk stemming from strong wind is the effect on fuel planning and options. If the airport beneath you is unlandable at the moment, it might just be transient phenomena tied to a frontal passage. Conditions might improve if you wait, or not, and you should have a backup airport, know how far away it is and how much time you have before you need to dip into your fuel reserves.

You should know how the runway orientations at your alternate airports compare with forecast or encountered winds. You also should know much fuel it will cost to get there and what kind of penalty you will pay for an upwind alternative. Your fuel status will tell you how long you have to loiter above your Plan A airport, then change your plans and make it to your alternate while still staying within your fuel reserves.

The bottom line? The decision space narrows as wind velocities approach the limits of the aircraft and pilot performance, and how the underlying weather pattern that is causing the winds is moving through the region narrows the options. It is a multivariate problem, and you need to know how conditions and your choices interact.

DON’T GET COMPLACENT

If your planned flight involves high winds, consider the myriad ways they can ruin your day, then mitigate accordingly, up to and including aborting the flight. Windstorms are often the result of unusual weather patterns that can defy forecasts, so maintain a questioning attitude. All your training and study is for a reason. High winds demand all your skills, attention and judgment, including the right to say no…there is no need to be blown away.