Piper’s PA-28 Cherokee models have been more or less in constant production since 1964. While there have been a wide range of changes to the original two-seat design introduced back then-bigger engines, tapered wings, retractable landing gear and stretched fuselages-the same basic airframe and related components will remain in service for decades to come.

Yet, as with all airplanes as time marches on, wear and tear take a toll on the way various mechanisms work, and better designs often are available to replace them. That’s especially true when it comes to the PA-28 fleet’s sidewall-mounted fuel selector, the current design of which now is in its third generation. The original design-generation 1, or Gen1-did not have much in the way of a detent protecting against inadvertent repositioning, nor does it prevent over-rotation leading to unintended movement to the OFF position. These characteristics aren’t the most desirable in a fuel selector assembly, especially since the component is mounted in the sidewall under the pilot’s left knee, where it can be difficult to view.

Existing Paperwork

After 1971, Piper mounted two different improved designs, the generation 2 and generation 3 (Gen2/Gen3) to minimize fuel selector positioning errors. Current PA-28 production incorporates the Gen3 selector. The 1971 date is important because that’s when the FAA published airworthiness directive AD 71-21-08, which mandated exchanging the Gen2 selectors for the Gen3 version.

Since then, a Piper service letter (SL 590) in 1972 and an FAA Special Airworthiness Information Bulletin (SAIB CE-14-22, July 10, 2014) have been published, along with numerous updates to the initial Piper service letter, all which advise but do not mandate that owners/operators install the better-designed Gen3 version. According to the FAA’s August 1, 2019, airworthiness concern sheet (ACS), the FAA is responding to “a recent reported concern” and looking at whether an unsafe condition exists with Gen1 selectors.

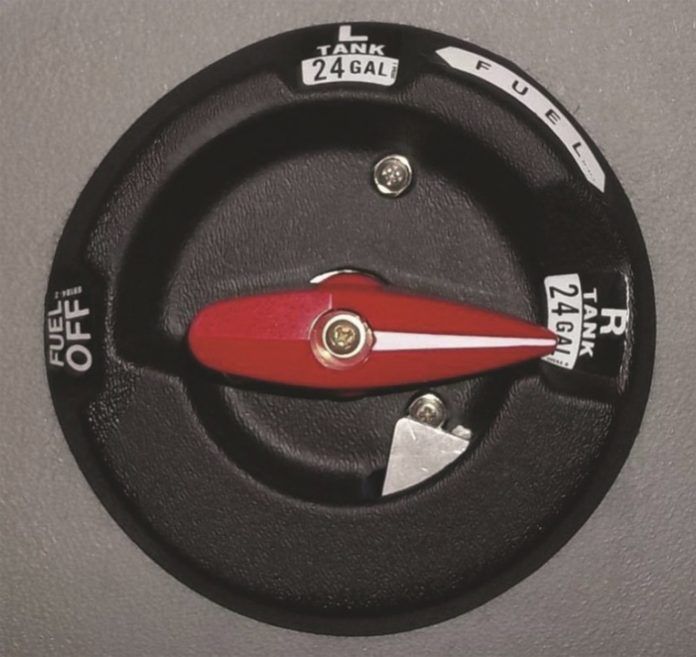

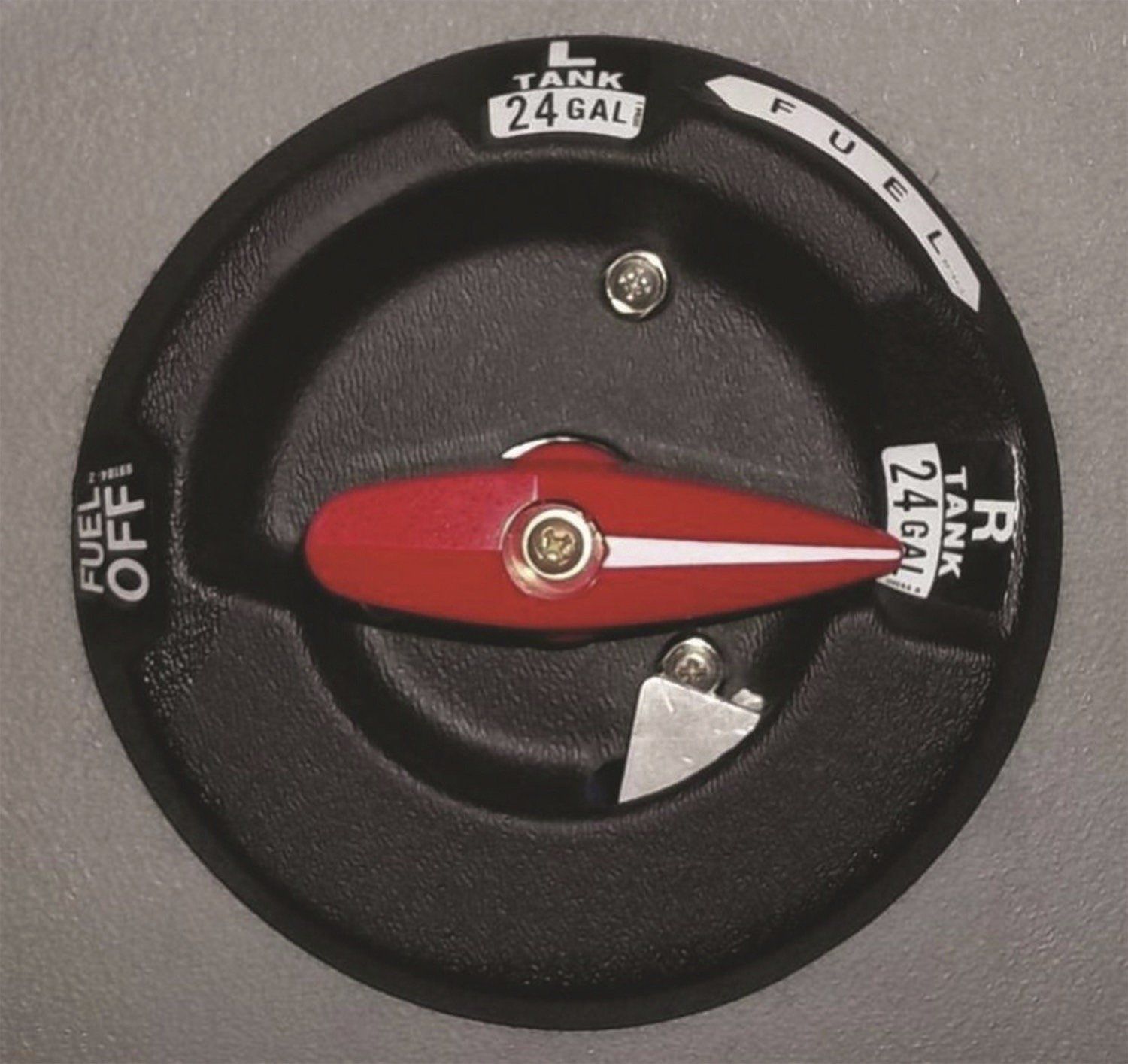

The Gen3 selector, pictured below, has two features that make it superior to the Gen1 version. One, it has a mechanical detent, preventing the selector lever from being rotated past the right tank back to close. Second, the detents for the three positions are better-defined. (Some PA-28 models may be equipped with field-installed supplemental fuel tanks and selectors that substantially differ from the factory component.)

Avionics, Too

Meanwhile, the FAA also has an ACS out for discussion on the FreeFlight FDL-978-XVR ADS-B transceivers. According to the ACS, “We have received reports of latent failures of FreeFlight model FDL-978-XVR ADS-B units. Troubleshooting determined that some units failed completely, while other units failed intermittently. Attempts to update the software and change any unit settings failed, as most parameters were ‘greyed out’ and unable to be changed.

“Additionally, the failed units gave no indication of failure to the pilot,” the ACS said.

Through the recent ACS, the FAA requests that “any users of the FreeFlight Systems model FDL-978-XVR ADS-B units who have experienced similar failures contact the FAA point of contact listed above with the unit’s model, serial number, whether ADS- B In and/or ADS-B Out fails to function, and whether or not an error was detected by the unit’s self-diagnostic.”

Developing A Process

The process leading to developing and distributing airworthiness concern sheets had somewhat typical beginnings: The FAA decided to take an action opposed by the industry segment affected. That segment happened to have a better solution than the FAA, though the agency took a lot of convincing. Out of that process grew a commitment for the FAA to reach out to industry participants knowledgeable about the agency’s area of concern. The commitment is formalized in agency policy as the airworthiness concern process, or ACP, in a supplement to the FAA’s Airworthiness Directive Manual (FAA-AIR-M-8040.1).

According to AOPA, the ACP “provides the GA community some much-needed access to the FAA’s continued airworthiness process. As the GA fleet continues to age and manufacturer support continues to dwindle, increased industry participation in the development of airworthiness actions is necessary to ensure the continued operational viability of the GA piston fleet.”

Why is all this important, or even of interest to the typical pilot? Before the ACP, the first notice the industry might receive of an airworthiness concern was a proposed-sometimes emergency final-rule imposing an airworthiness directive without the FAA having done its due diligence-what some might call its homework. That’s because, in part, owners/operators and type clubs often may know more about airworthiness issues with their aircraft-and how to mitigate those issues-than the FAA. By developing the ACP, which includes specific steps for FAA managers to take in developing an airworthiness directive, both “sides” of any debate about a proposed AD can avoid surprises.

Among its other features and according to AOPA, the ACP requires the FAA to “solicit industry input before proceeding with a proposed or final AD-except in emergency situations. Upon identifying a concern, the FAA must detail the concern on an airworthiness concern sheet and distribute it to appropriate organizations and type clubs for input.” That’s a good thing all around.

GoingSupersonic

In 1970, the FAA began developing regulations restricting supersonic flight over the U.S. Now embodied in FAR 91.817, the FAA prohibits operations at greater than Mach 1 on noise limitation grounds. The regulations include a procedure to accommodate “special flight authorizations,” but do not provide any kind of blanket relief for FAR 91.817.

As the underlying technologies evolve, industry interest in reviving supersonic aircraft-both as commercial transports and as business aircraft-is on the rise. Recognizing the ongoing development of supersonic aircraft, the FAA in June published a proposal “to modernize the procedure for requesting these special flight authorizations.”

The FAA says it has granted only three authorizations for supersonic flight over the U.S.: two for flights testing an experimental space vehicle attached to an airplane, and one for a domestic manufacturer whose subsonic airplane needed to exceed Mach 1 during required airworthiness testing.” But the FAA expects renewed interest in authority to operate flights in excess of Mach 1, and is proposing updates to the existing application procedures.

The FAA’s proposal is essentially a blank canvas for the agency and industry to develop operating rules for the supersonic aircraft everyone knows are coming. In responding to the notice of proposed rulemaking, the AOPA advised the FAA that one of its primary concerns will be the altitudes at which supersonic flight would be allowed. Specifically, the association is concerned that the existing 250-knot speed limit below 10,000 feet msl isn’t sufficient, and that Mach 1 should only be exceeded by aircraft in Class A airspace, i.e., at or above FL180.

“In order to determine whether a subsonic speed restriction may be required between 10,000 feet MSL and FL180, AOPA requests that the FAA, in collaboration with other industry groups and the Department of Defense, conduct a safety risk assessment and safety study to assess the effectiveness of see and avoid when supersonic aircraft are in question,” the association wrote to the FAA. “These studies should analyze not only how applicable speed restrictions may vary based on airframe and equipage, but also how the size and appearance of several of the supersonic aircraft being designed might make see and avoid challenging.”

Given the potential dangers, AOPA wrote, “…we believe that the FAA should study whether subsonic speeds below Flight Level 180 (FL180) should be required. The FAA should scrutinize any overland application for supersonic speeds below FL180 that do not include effective mitigations for see and avoid.”

Piper Fuel Selectors

By way of its August 5, 2019, airworthiness concern sheet, the FAA is requesting input from owners and operators of PA-28 models with the so-called “Generation 1” (Gen1) round, flat-plate fuel selector installed. The FAA wants to know:

• Have you had any issues with a Gen1 fuel selector resulting in fuel management concerns (i.e., mistakenly selecting the OFF position instead of the intended tank)?

• Do you have any concerns with operation of the Gen1 fuel selector, regardless of whether any issues with the fuel selector resulted in fuel management concerns?

• Are there any specific concerns related to a possible FAA action to issue an AD mandating removal of Gen1 fuel selectors and installing the Gen3 fuel selector to minimize the risk of unintended fuel management errors?

If so, the FAA wants to hear from you. Contact Boyce Jones of the Atlanta Aircraft Certification Office on 404-474-5535 or email him at [email protected].

When Can You Turn Off Your ADS-B Out?

One of the FAA’s rules regarding ADS-B is the requirement that, if installed, the ADS-B Out portion of any equipment must be on at all times. This differs from earlier rules for aircraft equipped only with a Mode A/C transponder, which allowed turning off the unit when not in airspace requiring it. Now, the FAA wants to create some exceptions to that rule, allowing ADS-B Out to be turned off in some circumstances.

In July, the agency published an interim final rule “to provide relief” from the always-on regulation for “government agencies that operate aircraft equipped with ADS-B Out but need the ability to terminate the transmission signal when conducting sensitive national defense, homeland security, intelligence and law enforcement missions.”

That rule also included a second exception, which generally would be available when civil or military aircraft operate in formation flight. The example found in the interim final rule states that during formation flight, multiple identification tags and/or alerts can clutter the radar display, making the ATC function more difficult. As such, the rule “allows ATC to direct only the lead aircraft flying in formation to transmit ADS-B or operate his or her transponder.” The interim final rule went into effect July 18, 2019, and may be revised in the future, depending on public comments received.

Proposed Miami/Fort Lauderdale Airspace Revisions

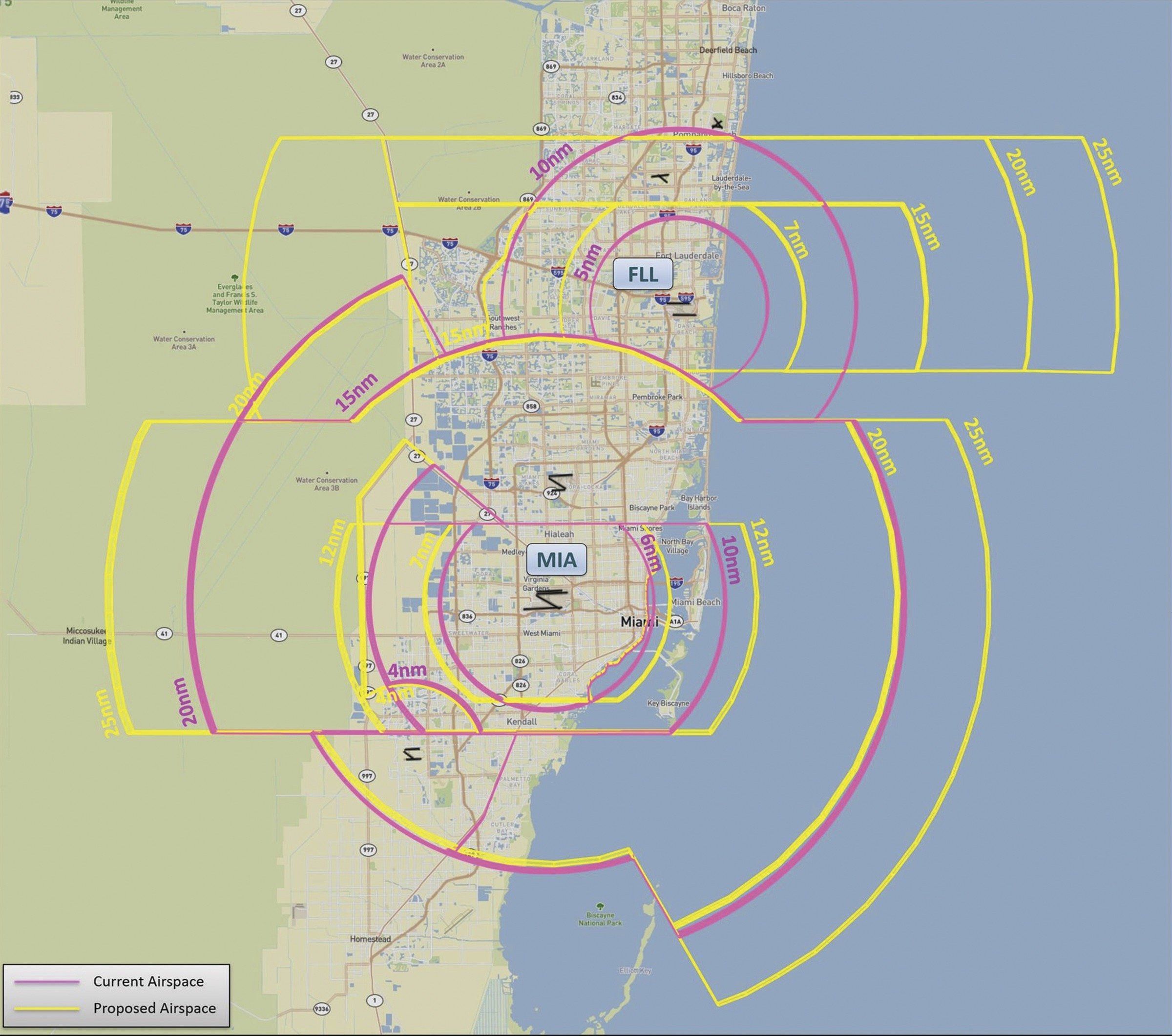

Earlier this year, the FAA began what likely will be a lengthy process to revise the Miami, Fla., Class B airspace, making it larger. Presently in something of a discussion draft, the agency released the graphic above, showing the existing Class B airspace in red and the proposed extensions in yellow. Presently, MIA’s Bravo tops out at 7000 feet msl, with bases varying from the surface to 1500, 2000, 3000 and 4000 feet msl.

At the same time, the agency is proposing to substantially enlarge the adjacent Fort Lauderdale, Fla., Class C airspace. Under the FAA’s working proposal, Lauderdale’s Charlie would be modified from its current 10 nm radius to create an oblong shape, extending 25 nm to the east of FLL and 20 nm to the west. The current (red) and proposed configuration (yellow) for the Fort Lauderdale Class C airspace also is shown in the graphic above. The existing FLL Class C airspace tops out at 4000 feel msl, with its inner area’s floor at the surface and an outer area with a floor at 1200 feet msl.

Some local pilots aren’t happy about the proposal, especially those extensions over the Atlantic Ocean and the substantially increased size of FLL’s Charlie. Loyal reader and frequent commenter Luca Bencini-Tibo, who is based in the area, points out one of the major issues in the redesign will be the size and shape of the Class airspace centered on Fort Lauderdale.

“The expansion would put more light GA out over the swamp or over the Atlantic. Going through FLL Class C has not been an issue, but MIA Class B usually ‘unable’ for VFR transitioning aircraft,” he added, with the implication that an expanded FLL Class C won’t be as accommodating. Too, most Class C airspace is roughly circular, as is the existing FLL version. The oblong expansion “…could act as precedent for other Class C’s to expand their wings, so to speak,” Luca pointed out to us.

The FAA says it anticipates issuing a formal notice of proposed rulemaking in 2020, with requests for public comment, before considering a final rule at some point in the future.

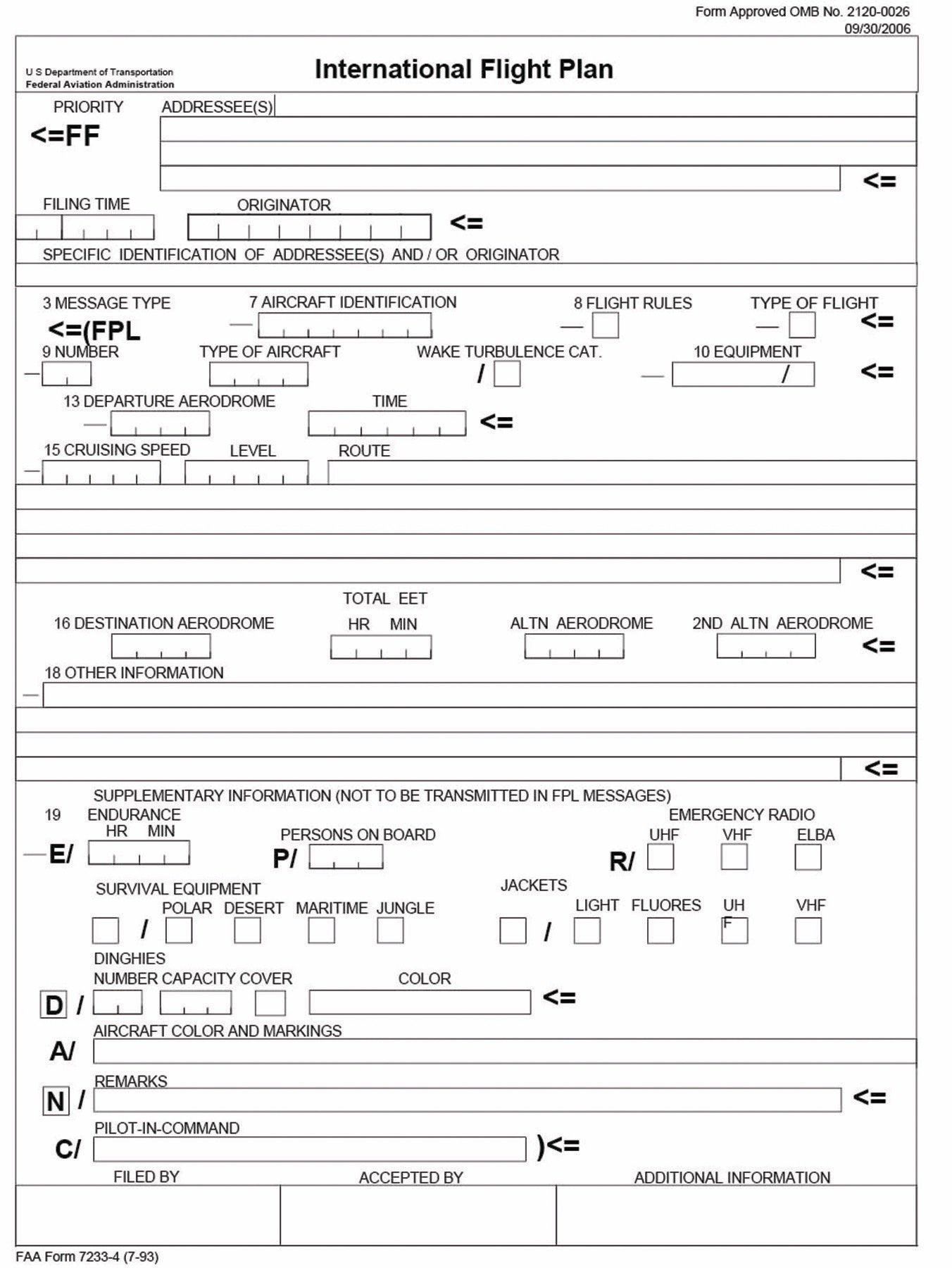

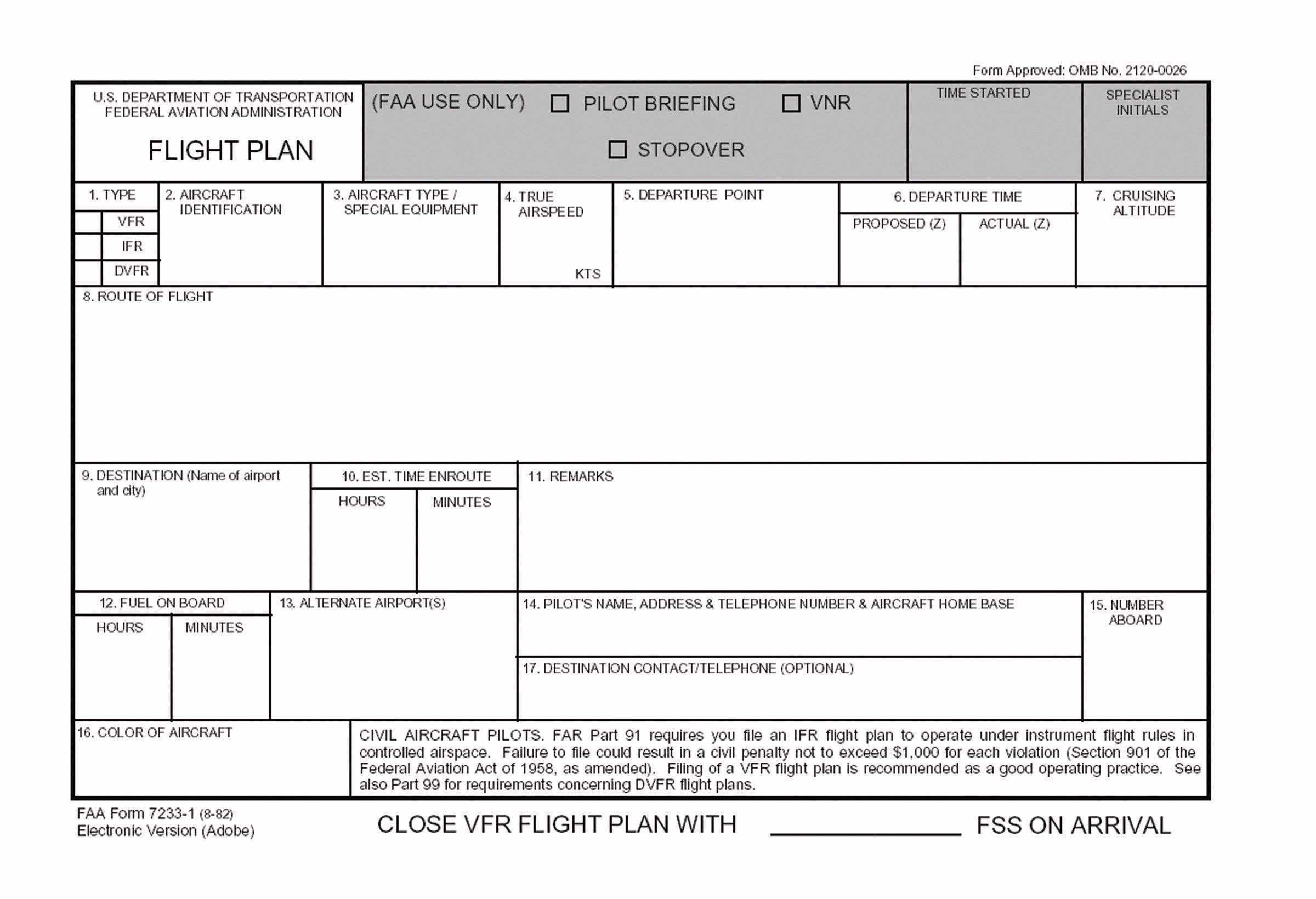

International-Format Flight Plans Go Into Effect. Finally.

After on-again, off-again fits and false starts over a few years, the FAA on August 27, 2019, formally and finally transitioned to mandatory use of the ICAO-standard flight plan format-also known as an international flight plan-for both IFR and VFR non-military operations.

“The change is part of an effort to modernize and streamline flight planning and supports the FAA’s NextGen initiatives,” a statement from the agency said. “The international format will also allow for integration of Performance Based Navigation (PBN) and enhance air traffic control services by allowing for easier identification of equipage, which can make greater use of airspace,” the FAA added.

Also according to the FAA, the international form is “easier and more intuitive for pilots to use and will increase safety.” The image at top right is the ICAO flight plan form in use by the FAA before the change. At bottom right is an image of the domestic flight plan form it replaces.

Among the benefits the agency touted in its statement are the following:

• An increase in the size of the departure and destination fields to allow a greater variety of entry types, including Special Flight Rules Area (SFRA) flight plans

• Transmission of the supplemental pilot data field, which contains pilot contact information, along with the VFR flight plan to the destination facility, to reduce search and rescue response times

• Air traffic control gains access to detailed equipment codes to identify aircraft capability

Guidance from the FAA on completing an international flight plan is available at www.faa.gov/go/flightservice.