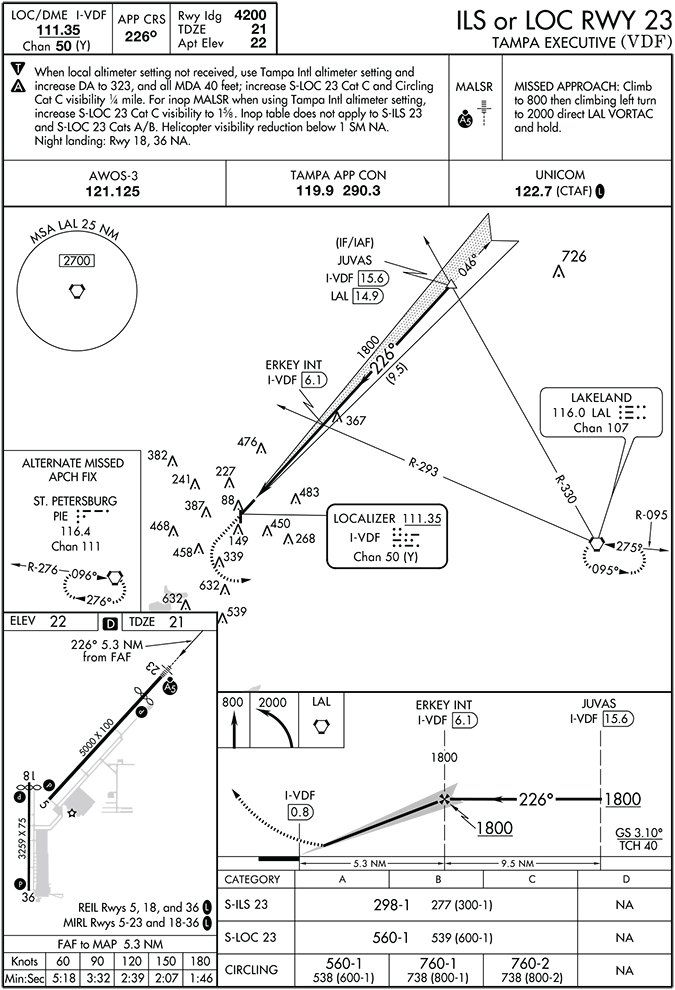

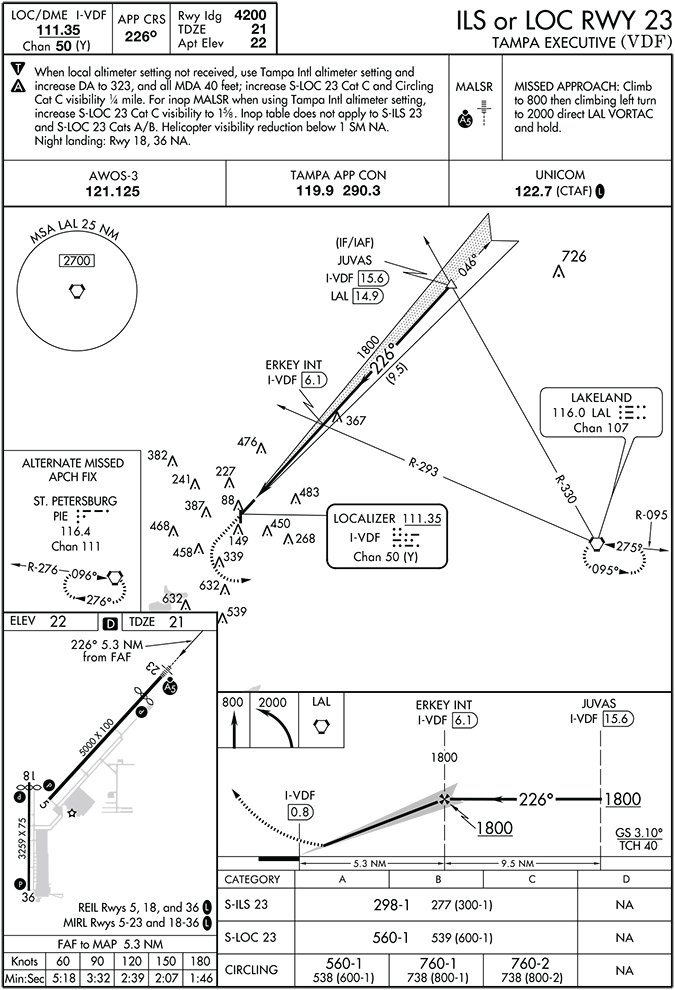

There I was, bouncing along on the miss from Vandenberg, err, Tampa (Fla.) Executive, KVDF. My instructor and I were flying the published miss after a practice ILS to KVDF’s Runway 23, which was to a hold over the Lakeland (LAL) Vortac. We wanted to enter the published hold, then do the VOR/DME A into KGIF, Winter Haven, Fla.’s, Gilbert Field. Those approach procedures are reproduced below, with enlarged excerpts.

The good news about this plan was the VOR/DME procedure we wanted to fly into Winter Haven used LAL as an initial approach fix. The middling news was we were doing this at 2700 feet msl, 700 feet above the minimum crossing altitude at LAL, to stay above KLAL’s Class D, which tops out at 2600. So I’d need to carefully pull the plug after crossing LAL to ensure I could get down to the MDA before getting too close to the airport. But the hold at LAL coming off the miss at VDF had us going the opposite direction, and we were trying to do this on our own, using published procedures.

Real World vs. Training

In the real world, this wouldn’t have been a problem. One of two things would have happened. First, on going missed at KVDF, we’d have gotten at least one vector from Tampa Approach. It would have been to the east to get us headed away from KVDF. If traffic and other factors permitted, we could have been cleared to intercept the VOR/DME A final approach course from that vector and motor off toward LAL. An approach clearance would follow.

The other thing that could have happened is ATC clearing us for the alternate missed approach on missing the ILS at Vandenberg. That calls for flying to the St. Petersburg Vortac (PIE) and entering the alternate published hold. Which clearance we would have gotten depends what we may have requested, what ATC knew about our plans—and when they knew it—plus traffic.

But we were doing this for training, in severe-clear VFR, trying to do it all on our own and not get too involved with ATC. (Sometimes, learning the procedures and trying to think on your feet is more important than talking to ATC, especially if you already know how to do that.) Without a vector from ATC or additional routing, how can we transition from the hold over LAL with an inbound course of 275 degrees to the VOR/DMA A final approach course of 071 degrees?

The simple fact is we couldn’t get there from where we were. A note on the VOR/DME A approach plate stated the procedure was not authorized when arriving over the LAL Vortac on certain radials. We were holding on LAL’s 095-degree radial, which is included in the range of radials from which beginning the procedure is not authorized.

There probably is some published, formal answer to the question of how to make that course change but, later, when we were on the ground, two seasoned instrument instructors didn’t know what it would be. In the end, my instructor simply “vectored” us into a teardrop turn to the right as we crossed LAL, then left to roll out on 071 to fly the next approach. Easy, peasey.

This “problem” really is more of a thought experiment, though, perhaps useful only for gaming out Nordo scenarios. In the real world of IFR flying and working with ATC, there are other options. But it got me to thinking about course reversals generally, plus procedure turns and their variations. Oh, and DME arcs.

Procedure Turns 101

I’ve been doing this a while, but I can count on both hands the number of times I’ve had to do a for-real procedure turn, with a few fingers left over. The simple reality is the radar environment we enjoy in the U.S. precludes much of the need for and drama of procedure turns. But that doesn’t mean we don’t need to be ready for them.

Of course, a procedure turn is what we perform when we need to reverse direction to place the aircraft we’re flying on a published segment of the approach. That’s usually the final approach course (FAC) and the maneuver typically begins after crossing the final approach fix outbound, flying away from the destination airport. Unless otherwise specified for our flivver, we have 10 nm of airspace from that fix to get turned around.

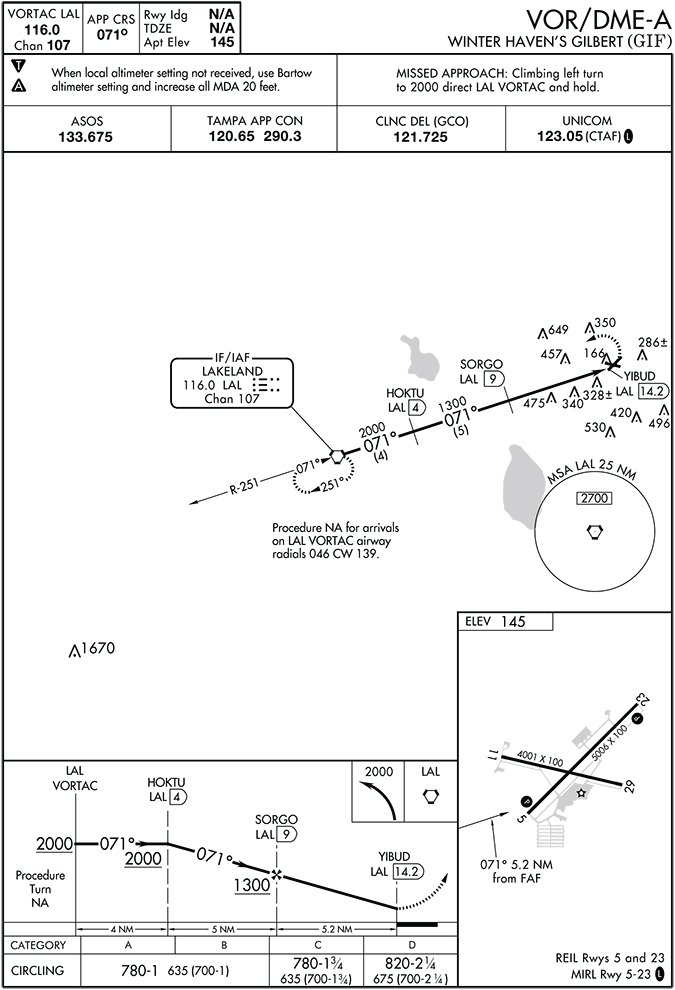

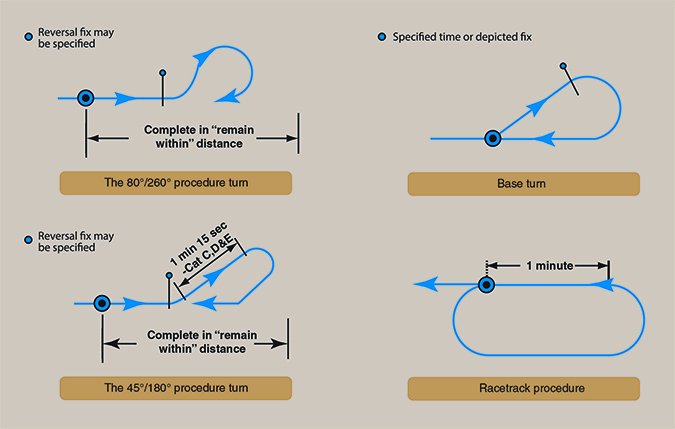

The exact turns we make to realign ourselves with the final approach course can vary, though, as highlighted in the diagrams above and the example below. Generally, the procedure turn we’ll fly will be of the 45/180 variety in the lower left, above, where we fly outbound from the fix for a minute, then turn 45 degrees left or right—depending on what’s charted—proceed for another minute, then turn 180 degrees in the direction opposite our 45-degree turn. This puts us on a heading to intercept the final approach course inbound at a 45-degree angle. From there, we rejoin the FAC, fly inbound and execute the approach. We do all this at the cleared altitude or no lower than the minimum published for that segment.

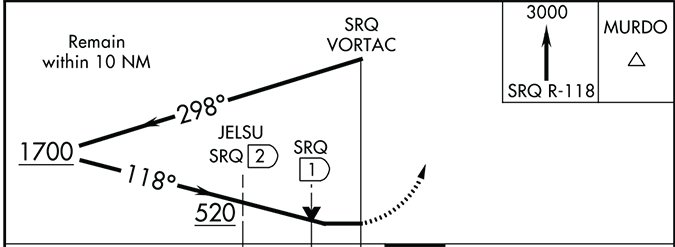

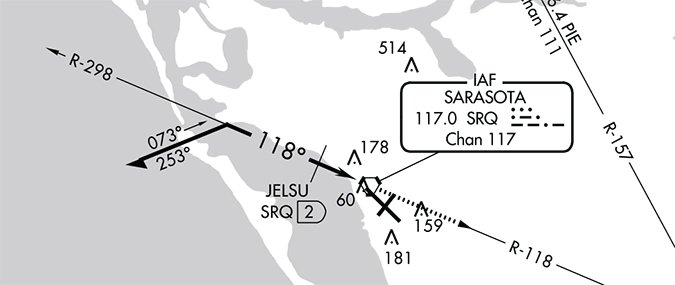

Some caveats are in order, of course. Typically, the procedure turn will be charted as a barbed 45/180, an example of which is the VOR Runway 14 procedure at KSRQ, excerpted below. A procedure turn or other course reversal is not to be executed when we’re not being vectored to join the FAC, when the symbol “No PT” is depicted on the initial segment being flown or when conducting a timed approach from a holding fix. And when was the last time you conducted a timed approach from a holding fix?

If the course reversal is not required for the above reasons, we can still request it, whether for training, experience or because we need a few minutes before executing the approach. No one likes surprises, especially ATC, so request and receive the clearance you need from ATC. Don’t presume you can fly one at will under IFR when it’s not required. When being vectored to the FAC, ATC may specify you’re cleared for straight-in (i.e., no procedure turn), to ensure the pilot understands it’s not to be flown.

The altitude to fly during all this also can be an issue. According to the FAA’s Instrument Procedures Handbook, FAA-H-8083-16A (IPH), “Absence of a chart note or specified minimum altitude adjacent to the PT fix is an indication that descent to the procedure turn altitude can commence immediately upon crossing over the PT fix, regardless of the direction of flight.” The excerpted profile view of the VOR Rwy 14 procedure at KSRQ at the top of this page shows we may descend to 1700 feet upon crossing the SRQ Vortac outbound. Once inbound from the procedure turn, we can descend to the MDA, 520 feet.

Variations

A holding pattern may be published/specified in lieu of a procedure turn as the preferred course reversal. Like the procedure turn itself, the hold usually is based on a final approach fix. As with any other hold, the distance or time specified must be observed. For a hold-in-lieu-of PT, enter and fly the hold as depicted, observing applicable speed limits.

The holding pattern maneuver is completed when the aircraft is established on the inbound course after executing the appropriate entry. “If cleared for the approach prior to returning to the holding fix and the aircraft is at the prescribed altitude, additional circuits of the holding pattern are not necessary nor expected by ATC,” sayeth the IPH.

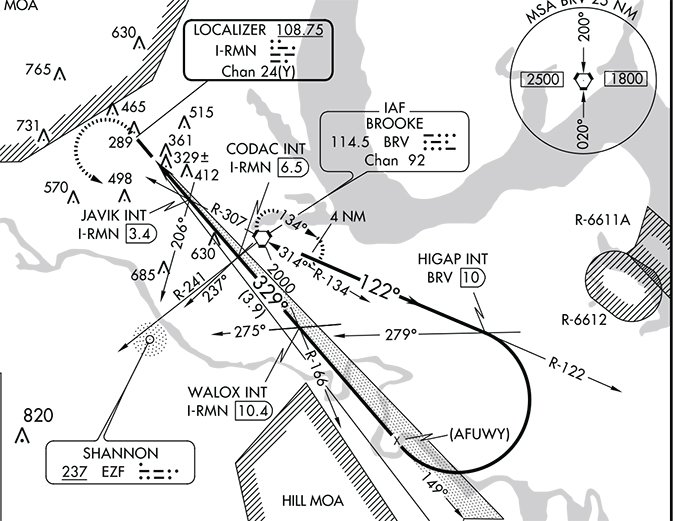

Another type of course reversal you may see is the teardrop pattern. It’s reproduced in the diagrams on page 13 and an example is shown in the middle on the opposite page, from the ILS Rwy 33 at the Stafford (Va.) Regional Airport, KRMN. When it’s depicted (instead of a hold, for example) it must be flown.

The published teardrop procedure is actually fairly easy: Depart the approach fix outbound on the depicted course. If no mandatory fix is depicted, start a turn in the indicated direction so as to complete the maneuver within 10 nm or the distance specified. Roll out on the specified inbound course at or prior to the fix.

One thing the teardrop affords us is the ability to make basically one turn while losing considerable altitude and still remaining in a relatively small area. When the fix you’re using is the final approach fix, and is on the airport, we’re “considered to be on final approach upon completion of the penetration turn,” according to the FAA’s Instrument Flying Handbook, IFH, FAA-H-8083-15B. The final approach segment begins on the FAC 10 nm out.

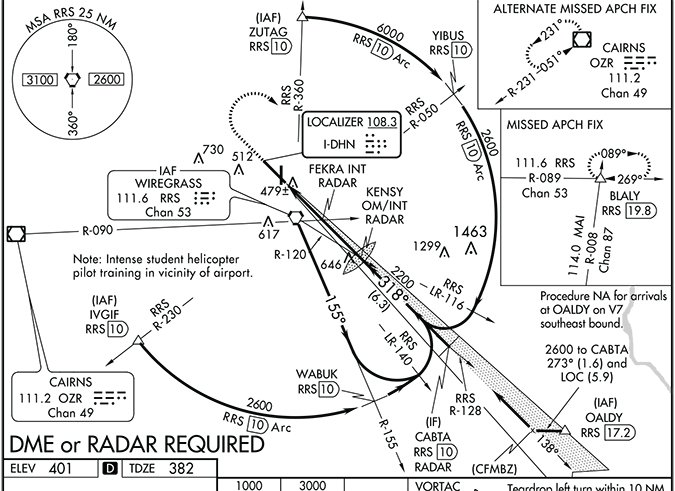

Perhaps the mother of all approach-related course reversal maneuvers is the DME arc, an example of which is presented at the bottom on the opposite page. That’s from the ILS or LOC Rwy 32 procedure at the Dothan (Ala.) Regional Airport, KDHN. If you wanted a course reversal to drag on a long time, require constant turning and monitoring, and offer the most opportunity to make errors, you’d probably design something like a DME arc. The sidebar above, adapted from the IFH, details how to fly one.

One of the keys to successfully flying a DME arc is to limit your heading changes. When turning away from the center of the arc, limit yourself to 10 degrees. When turning toward the center, turn no more than 20 degrees at a time. This presumes the idea is to remain 10 nm from the depicted fix, which is nominal for charted DME arcs. As always, practice makes perfect.

Turning Around Is Fair Play

Since ATC generally wants to be a step or three ahead of you, it’s not at all likely you’ll ever get into a situation like my instructor and I did—no way to get from where we were to where we wanted to be. That said, we often practice only holds or 45/180 procedure turns, and we rarely even think about teardrops or DME arcs. But there are several published course reversals out there. We’re expected to be able to fly them all, not run home to Momma for a vector.

Jeb Burnside is this magazine’s Editor-In-Chief. He’s a 3200-hour instrument-rated ASEL/ASES/AMEL commercial pilot and aircraft owner.