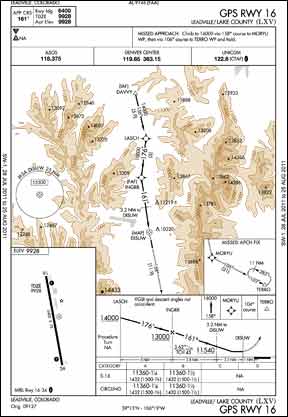

I had almost the same experience (“Open-Door Policy,” Learning Experiences, August 2011) with my father. It was just after WWII, and I was 10 or 11. He had a Piper Cub. It was a nice, late summer evening and we had just taken off from the Whitman County Airport in Eastern Washington. The window was open and-why, I dont know-I reached up and pulled its quick release. It promptly fell off, but my dad had seen me do it and, as luck would have 288 it, caught the door! He calmly reached around with it, handed it to me and said “Hang on to it; Ill land and well put it back on.” Which we did, on a hilltop in wheat stubble out in the middle of nowhere. Bill Henry Look Out Below Concerning Crista Worthys inquiry about altimeter setting changes in the Grand Canyon area (Unicom, August 2011)-or any other area where altimeter settings are obtained at different elevations-the reason is the non-standard pressure change with altitude when temperature differs from standard. Remember the old “pressure or temperature is low, look out below” rule? When the temperature is warmer than standard, the true altitude will be higher than the indicated altitude. Any non-standard altitude altimetry errors are accounted for in the altimeter setting received at a particular elevation, and the altimeter will read to correct airport elevation when at the observation airport. On a warm day, the atmosphere expands, and the altimeter error begins to accumulate as the airplane climbs above airport elevation. On a hot day of 30 deg. C above standard (about 100 deg. F/40 deg. C at sea level), the altimeter error is almost 10 percent of the height above the altimeter setting reporting elevation. For example, at a temperature 30 deg. C above standard, if the altimeter setting is 29.90 inches at an elevation of 2000 feet and the airplane is at 6000 feet indicated altitude (4000 feet agl), the altimeter error will be about 400 feet and the true altitude will be about 6400 ft. If there is an airport located at the 6000-foot elevation in close proximity to the 2000-foot-elevation field, the altimeter setting will be approximately .40 inches higher than at the lower-elevation airport, or 30.30 in this example. Ive taken my students on mountain checkouts from Wichita, Kan., to Leadville, Colo., dozens of times, and on summer days, I have always noticed a big difference in altimeter settings between Pueblo, at about 4800 feet msl, Colorado Springs, 288 about 6000 feet, Leadville, almost 10,000 feet. Large changes in altimeter settings over a short distance-with elevations being more or less constant-normally would indicate strong pressure gradients and wed expect strong winds. But the winds in Colorado were quite mild when I observed the large pressure changes. After observing this phenomenon on many flights, the lightbulb finally came on: This is due to non-standard atmospheric conditions. As I write this, altimeter settings and temperatures are 30.15/22 deg. C at Pueblo, 30.24/23 at Colorado Springs, 30.48/18 at Leadville, and 30.76/10 at an AWOS location adjacent to Monarch Pass and at about at 12,000 feet msl. Standard temperature would be +5 at Pueblo, +3 at Colorado Springs, -5 at Leadville and -9 at MYP. Therefore, the actual temperatures are presently about 20 deg. warmer than standard atmosphere, translating to an altimetry error of about six or seven percent. Considering the elevation difference of about 4000 feet between Colorado Springs and Leadville, the difference in altimeter setting should be about .24 to .28 inches, which corresponds to the current Metars. There is a window on the good ol E6B for altitude corrections; we just usually dont work those problems, and they are not part of any FAA knowledge exams. Incidentally, you can check your true altitude on the altitude display of any GPS. When you are on the ground, the altitude displayed on the GPS will be fairly close to the field elevation. On a hot summer day, when you are at 6000 feet agl, the GPS altitude probably will read 500 feet higher than the altimeter. The altitude errors associated with low temperatures are one of the reasons minimum IFR altitudes are 2000 feet agl in mountainous areas: If its 15 deg. C colder than standard, the true altitude will be about five percent lower than indicated. If the MEA is 10,000 feet above the altimeter setting reporting elevation (typical in Colorado), youll be 500 feet lower than indicated. Another reason for altimeter setting changes over desert areas in the summer can be a so-called “thermal low.” Extreme heating in the desert causes the air to rise, 288 creating a localized low pressure system, which will fill in again at night as the air cools. Herb Pello, ATP, CFI-ASMEI Training Reform While Im sure there were some good ideas put forth at the SAFE Pilot Training Reform Symposium (“Will Training Reform Help Reduce Fatals?” July 2011), I dont believe the root causes of our current pilot training problems are being addressed properly. My view is that we are not even training to the standards that are in place. As an examiner, I have seen candidates who dont know how to trim an aircraft properly, fly it almost exclusively with the autopilot (which they dont know how to use properly), think they can fly an airplane without an altimeter, look out the window and cant see a 10,000-foot runway, cant tune a VOR frequency, etc. Can a 250-300-hour wonder train to do these things? Of course. Do examiners pass candidates who cant? Unfortunately, also yes. Many of the training community cant or wont adhere to standards that are in place, so there is no wonder the accident record is what it is. Unfortunately, when the author makes the statement that “…on an instrument practical test, it might be more realistic to see an applicant conduct a safe circling approach to minimums rather than a steep turn under the hood,” he loses almost all credibility with me as someone who is engaged in the training process. The steep turn has been eliminated from and the circling approach has been in the instrument practical test standard for well over five years. Sorry, there is no magic bullet for training. There are standards, but a significant portion of the aviation community does not seem to want to train to them. David Shields, ATP, CFI, DPE

Spokane, Wash.

Benton, Kan.

Via e-mail