I had passed my instrument rating checkride two weeks earlier, and my wife and I had flown to Palm Springs, Calif., for our anniversary. It was time to fly back to the San Francisco area, but the weather wasn’t cooperating. Severe rainstorms in the Los Angeles basin and thunderstorms over the Mojave Desert that morning meant we weren’t going anywhere soon.

The coastal route avoided convective activity, but likely would have us in constant rain and IMC the entire route, and limited our altitude due to potential icing above. The route over the western Mojave showed severe convective activity, but it was moving east.

As the morning waned, the weather picture improved greatly, with only scattered showers and clouds over the Mojave Desert and clearing over the west side of the Tehachapi Mountains. We ended up filing to go over Victorville and into Bakersfield to visit family. Soon, we were cruising in VMC at 10,000 feet and looking at the activity over the Mojave. Ahead, there were Pireps for icing above 8000 feet, so we asked for and received routing over Edwards AFB at 6000. Based on what we saw visually and on the FAA’s flight information system (FIS-B), we thought we were well out of danger.

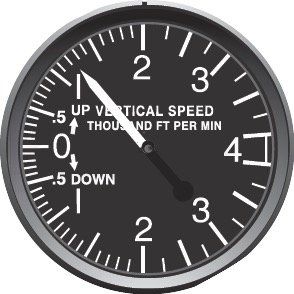

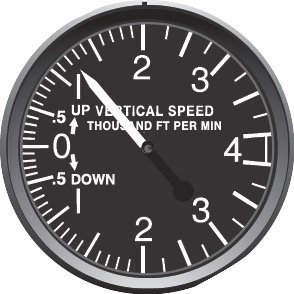

And we were, until skirting the western edges of the weather in VMC. One of the building rainstorms sucked us upward at 1000 fpm and into full IMC with heavy rain and hail. I was back on instruments, and I started a shallow 180-degree turn to reverse out of the storm. It was very loud and very dark. Within two minutes we had reversed course, we were out of the updraft, hail and rain, and I was able to descend back to 6000 feet again over the desert. The updraft had carried us to 8000 before we got out of it.

Of course, ATC saw the whole thing and asked if we would like to “…take a break? Looks like you had a roller coaster ride there.” I declined the offer and the controller gave us a block altitude from 4000-10,000. We proceeded on to Bakersfield without further issues.

Looking back, we were very fortunate to escape that system and come out alive. Later, I replayed the FIS-B radar returns, and it was clear that we had flown right under and then into a severe thunderstorm. In the moment, I had relied on the FIS-B weather reporting and thought we could get under the trailing edge of the storm by going down to 6000, but we did not account for FIS-B’s Nexrad weather radar’s inherent latency. We had flown under—and gotten sucked up into—a cell that wasn’t on our in-cockpit display.

Since that episode, we do not mess with thunderstorms, and get no closer than the FAA-recommended 20 miles to any convective activity.