Theres no way the FAA can come up with a regulation covering every possible scenario, which is a good thing. If they did, wed rarely be able to roll our airplanes out of their hangars except on the clearest of days when no airliners were about. So, the FARs set certain minimum standards for pilots and once we determine were 288 in compliance, its up to us to decide if the proposed operation is safe, morally acceptable and non-fattening. Or something like that. Frequently what we want to do complies with both the FARs letter and spirit. Sometimes its borderline; certainly legal but safe only if everything goes our way and nothing on the airplane breaks. And then, there are occasions when the proposed operation is both legal but really not smart. Hilly Scud Many thousands of words have been written about the wisdom (or lack thereof) of scud running. To be sure, the old-school practice of flying below a cloud deck has changed-for the worse-with the propagation of power lines, towers and other obstructions. And the vicious companion of scud-running is the question of visibility. Aviation Safety

“As an attorney, Ive been involved in a couple of lawsuits in which people were legal in visibility that ranged from one to three miles. They were legal in terms of the airspace and the visibility, but they hit towers. One of these really tall towers is 1000 feet tall, about 20 miles south of Grand Rapids, and it was directly in the planned route of the accident pilot.”

While the towers are required to be lit, lights can, and do, burn out, and the guy wires can be invisible fly traps for planes. Durden believes that the guy wires should have visible balls or other markers on them. He continues, “It is legal to fly below 1000 feet in three-mile visibility, but with the proliferation of towers, its just dumber than hell.”

California CFI/MEI Phil Blank flies a TR182 out of Livermore, Calif. Hes also a flight examiner for the California Wing of the Civil Air Patrol. And where there is terrain, there is the opportunity for the CAP to come looking for those who tangle with the pointy rocks. Blank notes terrain features such as Southern Californias Banning Pass have their own brand of siren song for VFR pilots.

“Lets say youre returning from a wonderful weekend in Palm Springs; youre based in Riverside and do this trip frequently. Unfortunately, when youre ready to go home, low stratus is blanketing the L.A. Basin and comes up to the western edge of the pass. Youve flown this dozens of times, and the weather in Riverside is 1000 overcast and miles. What the heck-you can just follow the roads. After all, you know the area like the back of your hand.”

Okay, so technically, you were probably not within controlled airspace, but flying

288

the highway 500 feet above it can be dangerous. Helicopters and power lines can live in those low-lying hills. Too, you may find that your destination airport is below basic VFR minimums, forcing you to wait for a special VFR clearance, or divert to a clearer, more inconvenient airport. Have you been tempted to force the arrival rather than divert? To the VFR pilot who may be poking at the envelope, what sounds better: sweet-talking the FBO at Plan B Airport out of the last rental car, or feeling that ice-hot shot of fear down your back as you tap-tap-tap your way through the scud towards Plan A?

Other Visibility Issues

Just as overdriving your headlights on a foggy night isnt such a safe idea, the same principle applies to your chosen aircraft in marginal VFR. When youre flying in one- to three-mile visibility, terrain and other obstructions appear a lot more quickly when youre sizzling along in, say, a Bonanza or Cirrus than in a Cub or a 152. Your situational awareness in MVFR is critical when the closure rate between you and something hard starts to shorten up.

Another trap that can beckon us to the dumb side of the Force is that of expectations. We take off, we expect to land. And we dont always expect to lather, rinse, repeat when bad viz and weather stand between us and our destination. Although he was instrument-rated, Rick Lindstrom found himself in that situation some time back while returning to the Bay Area from Fullerton, Calif. There were multiple broken layers over the complicated airspace of the L.A. Basin, and his route took him over a layer while avoiding the then-TCA. While he could have filed IFR, his plane was not certified for icing, and the MEA in the area would have taken him into certain coldness.

As the layers gave way to mountain obscuration, Lindstrom pretty much pulled over to the side of the road; continuing into the increasing murk would have been, well, dumb.

288

Forty minutes and a cup of coffee later, a Bonanza pilot landed, reporting clearer weather along his route. Another takeoff and another landing on the way home ensued, as the weather worsened again. This time he gave up the flight for the night, stayed at Harris Ranch-its not so bad when the foods good-and continued the flight the next morning.

A simple decision? Youd hope so, but once youre underway, and you expect to complete the flight as planned, its smart to leave room for stopping multiple times, if thats what it takes.

“Once the conditions began to exceed my comfort level,” Lindstrom recalled, “I heard this little voice in my head: Why are you doing this? It was a good point, and I wasnt going to do it any more.”

Fuel Reserves

Durden puts it bluntly: “Every Federal Aviation Regulation arose out of a dead pilot. Some things that we do are legal, dumb and then lead to a dead pilot, which then become illegal. Learning from our mistakes is a good thing, but the fact that they were legal but almost dead is something to emphasize.”

Fuel exhaustion has accounted for 37 fatal general aviation accidents in the United States since the beginning of 2000; an additional 418 non-fatal accidents were recorded. Legally, you only have to launch with reserve fuel. That doesnt mean thats the best you can do.

Durden recalls that as a brand-new private pilot, he flew a commercial pilot to Missouri in a Cessna 177 to pick up a spray plane. On the way back, they were to fly together; he knew the spray plane had about three hours worth of gas. The

288

plan was to fly for two hours, then stop and get fuel.

“In an hour and 40 minutes, I lost sight of him because it was so hazy. He didnt lean the mixture, and ran it full rich. In level flight, at about 2500 feet, and this guy didnt lean the mixture. So he ran out of gas. It was legal but dumb not to fly the aircraft by the book.” The commercial pilot had been told that below 5000 feet, you run full rich-an old wives tale that caused serious damage to an airplane.

“He was okay-its hard to hurt yourself in a spray plane,” Durden continues. “He was strapped in and had a helmet on. He discovered it glided like a waxed sewer cover, and he couldnt make an airport, so he landed in a small field.”

“Landed” was a kind description. He hit a rusting school bus in that field, which tore off half of the left wing. He then tore through a ditch, collapsing the right-side landing gear, across a major highway, through another ditch and concluded the arrival in a parking lot. Durden said it got better: “A highway patrolman who saw the whole thing zoomed into the parking lot. The pilot emerged from the airplane, took his helmet off and stood there, cussing, as the patrolman asked, Have an accident? The pilot, still steaming, replied, No, thanks. Just had one.”

As a new private pilot, Durden was amazed this commercial pilot had believed that old wives tale. In an airplane with a big fuel-sucking engine, it made a real difference. The fuel endurance section of the owners manual (the 1971 plane was rolled out pre-POH) conditioned the figures on the mixture being leaned in normal cruise flight. “Now, its legal to fly at whatever mixture you want, but it sure is stupid to run it full rich.”

Against the Flow

While its a myth that straight-in approaches a non-towered airport violates the FARs, its a practice that requires a second thought.

Blank notes, “The AIM is very specific as to the types of patterns that should be flown, and for a reason. At a busy non-towered airports, there is often intensive student training. Theyre often doing touch and goes in the pattern and focused so

288

much on what they are doing that they are not checking final…and perhaps, not calling on the radio.” He adds that at more remote airports, radios are optional. Conditions could change during your descent or a different traffic pattern may be in use. Hes a proponent of entering the pattern on the 45, and taking a good look at the wind sock before stabilizing your approach.

On my first sojourn to Oshkosh, I got an eyeful of non-standard pattern flying. While flying left base in the left seat of the Tiger into Scottsbluff, Nebraska, I was very surprised to see a bright yellow Ag Cat crackle past us on a very short final, jumping the queue in his haste to land. He was based there, and the local safety counselor was not amused…but not surprised. (I was pretty scorched about it, too.) My lesson learned? Be ready. While the FARs lay down the law, not everyones on board, especially in their own back yard.

Mixing VFR and IFR traffic at such airports can be a serious issue-the en route environments leading to the same arrival airport are quite different.

When John Cooper was a new pilot working for NASA, he recalls, “I had absolutely no idea about the habits of IFR aircraft. I remember being told by approach, Be sure you stay below the ILS into Orlando Exec.” He was tempted to reply, “Whats an ILS?” He believes the fact that IFR aircraft can pop out of the clouds unannounced should be at least mentioned in basic pilot training, with some pointers on where and when that might happen.

Addison, Texas-based Dave Siciliano found it nerve-wracking to approach a non-towered field IFR, not knowing if he may come out of the clouds and meet someone unexpectedly. “Ive had occasions where the approach frequency was so busy, I couldnt make a call until well into the approach, when they turned me over to the CTAF. On one occasion, approach told me there were three folks in the pattern, radar coverage terminated, clear to change frequencies, contact us on the ground when I was about a mile from the MDA.

And speaking of mixing faster traffic with slow, Durden notes, “So many pilots are afraid of flying slowly, especially when they fly faster than the published approach speed-theyre afraid of stalling. So they think those extra 10 knots on approach

288

will keep the controls from feeling mushy. Its legal to fly faster than whats published, but its not that smart. Thats how you get loss of control and overruns.”

Since the beginning of 2000, there have been 21 fatal and 223 nonfatal general aviation overrun accidents in the United States. Some dedicated slow-flight practice, with an instructor if you want, will keep you much more comfortable at the low end of the speed envelope…and out of the Dumb File.

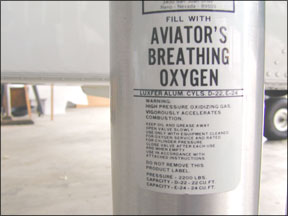

Deep Breathing

The advent of personal oxygen systems, such as those available from Aeromedix.com and Mountain High, has made it easier for pilots to fly in the mandatory-oxygen altitudes. So, theres not much of a rationale to get up there without it, and the physiological consequences can be severe. (See December 2007s issue of

Aviation Safety.) Even when you know its coming, hypoxia will steal your judgment and high-level capabilities. Like flying.Blank concurs. If youve gotten your normally aspirated plane up to, say, 11,500 feet to catch some good tailwinds, of course youll be careful to ensure youre not affected by the decreased oxygen. And you dont have to put the O2 on yet, anyway. Young, in good shape and a non-smoker? Youre not immune, especially if your flight continues into the evening. “You might even get flight following to keep you company, but for some reason, you cant quite figure out where you are, and youre having a hard time seeing the instruments. Get altitude training in an altitude chamber to experience what its like to run out of O2. Hypoxia is difficult to recognize, and youll feel good for a while. Many pilots put on the O2 at night at or above 5000 feet; your eyes are extremely sensitive to the lack of oxygen at night. It will help your visual acuity and keep your head clear.”

The Takeaway

Theres a lot more dumbness to go around, but staying aloft, on the runway or conscious is a good start. A pilot whos stuck on stupid can fix that pretty easily, either with a closer look at the POH, more detailed BFRs and dual sessions, a little extra effort, some consideration and some common sense. Its worth it.

Cory Emberson is a private pilot with several hundred hours and a contributing editor to KITPLANES magazine.