The tower controller reached for the crash phone several times before I finally set my feeble J-3 Cub down on the 9000-foot runway for a full-stop landing. Apparently, my desire to practice low-level engine outs was accompanied by the controller’s incipient heart failure. On my side of the mic, I was cleared for takeoff, so I did what I had planned: I pushed the throttle forward to the firewall, climbed as expected (perhaps a bit steeply given the wind and my goal of practicing the worst case, an engine out in VX climb), then yanked the power at 200 feet over the runway to simulate an engine out.

288

To maintain airspeed with no power and at a steep angle, I had to dive…rather steeply…bring it back to the runway, flare with just enough energy to spare. I then added power and did it again. The second time, only climbing to 100 feet. It was the same pattern, but with less margin. I finally did it again at 50 feet. Each time the maneuver is closer and closer to the ground giving you less and less time to react.

Three things inspired me to practice this maneuver. The first was one of Steve Tupper’s Airspeed Online podcasts, in which he interviewed a young man about soloing a glider, a Cessna 150 and a Piper Seminole on his 16th birthday. The second was watching a Carbon Cub during a Recreational Aviation Foundation (RAF) fly-in at Ryan Field Airport (2MT1), near Montana’s Glacier National Park. The third was a fatal crash of a Piper Twin Comanche at my home airport. These three aviation events were totally separate, but in my brain they created a need to practice engine failure on takeoff.

Father-Son PTSD

Let’s start with my first catalyst: Tupper’s April 2013 interview with Drew Gryder, and his father and instructor, Dan Gryder. The Gryders described one of the more unorthodox training practices I have ever heard of. In addition to the standard PTS stuff, Drew was relentlessly given engine-out simulations, frequently on initial climb. So rigorous was the drill that out of the 512 pre-solo logged landings, 400 were engine-out simulations. The episode is available online at tinyurl.com/avsafe-tupper.

When the elder Gryder pulled the power, young Gryder knew the drill. Point the nose down and don’t try to 180 back to the airport. His training was so rigorous, that the running joke was that he was more surprised when the engine actually kept running on takeoff. Listening, my first thought was it seemed like a cruel form of mental torture to simply trigger a Pavlovian response to do the right thing, but so is a father’s love.

After some reflection, I could see that expecting the engine to quit on takeoff is excellent “killproofing,” a conditioning and rigor lacking in my training. During my primary training, 30-plus years ago, engine-out simulations were common, though I don’t remember an instructor pulling power on takeoff or climb-out. It probably happened, but that was a long time ago. In the years since, any simulations have been mostly relegated to new airplane checkouts and occasional flight reviews, and typical engine-out practice has been from a cruise or pattern-altitude setup. I could see Gryder-like instincts weren’t going to come from doing engine-out exercises at altitude once every couple years. It was an inspiration to simulate the real thing for myself.

A Cub in a Climb

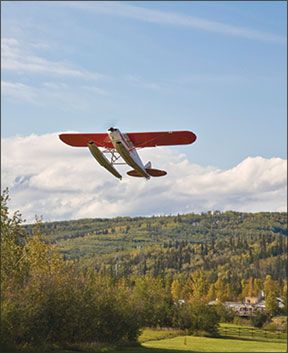

My second inspiration was the direct result of an offhand remark at the RAF’s Ryan Field Airport fly-in. A bunch of us were watching a Carbon Cub perform. With its 180-hp engine on one of the lightest-of-light airframes, it is the essence of purity in its power-to-weight ratio. It has incredible short-field performance, capable of taking off and climbing at an angle so steep it appears to be going almost vertical and clearing the proverbial 50-foot obstacle in not much more horizontal distance.

Since I frequently practice short-field takeoffs in preparation for the challenges of backcountry flying, I’m familiar with an aggressive VX angle of attack. With the STOL kit on my Cessna 180 and also in my lower-powered Cub, my deck angle isn’t anywhere near as steep, but I’m familiar with the thrill of aggressive climbs.

While I marveled at the Carbon Cub’s impressive performance, I commented to the guy next to me how exhilarating I found super-short field techniques. The 10,000-hour pilot replied nonchalantly, “If you think that’s exhilarating, imagine how it’d feel if you lost the engine.”

His throwaway comment struck me so hard I actually winced. Horsepower was making that plane climb, but take that full throttle out of the equation with a clogged fuel line or broken crankshaft and all of a sudden that steep angle goes from being an amazing asset to a shocking liability. And it’ll happen faster than you can change your underwear.

I could imagine the sight picture from inside the Carbon Cub at full power—nothing but sky. The “what-if” comment put a different picture in my mind. What would it look and feel like if the engine quit during such a climb? It made me think about what it would take to salvage the situation if you lost power in such an aggressive maneuver.

A Comanche in a Crash

My third inspiration for practice was the fatal crash of a Twin Comanche at my home airport last summer. The wreckage came down on the west side of the runway opposite my hangar’s location. Quick action by a parking lot attendant with a fire extinguisher probably saved the surviving passenger, but the crash angle and energy did not spare the front-seat occupants.

plane was at full power, as one would expect on takeoff. After that takeoff roll, lift off and climb, both engines apparently failed: Witnesses later reported they were “surging and popping.” When it was all over, there was a ball of aluminum that didn’t even resemble an airplane just to the right of the runway centerline. It all was just a bit close to home, so I resolved to remove the rust from my engine-out practice.

Kill-Proofing 101

My 1945 Cub has a more-powerful-than-stock 90-hp engine. It has the same airfoil as the Carbon Cub, but half the horsepower. When lightly loaded on a cool morning, she climbs like a scalded cat. I know in reality my deck angle is nowhere near as steep as the CC’s, but in a VX climb, the sensation is amazing. Now I was inspired to simulate the horror of having the engine conk out on initial climb, not because of the terror I’d feel, but because I knew I was not prepared for it.

I picked a day when I pretty much had the airport to myself, except for the tower controller. I called for a clearance to get multiple touch-and-goes on each pass. Then I started down the 9000-foot runway with all 90 horsies galloping away, lifted off and climbed at VX. I got 200 feet of air beneath me, yanked the power and pushed the stick forward to maintain what little airspeed I had. It wasn’t enough. I had to push further and further until I was essentially diving at the runway, and it was coming up to meet me…fast. My airspeed was still about the same, so I had enough energy to flare and touch down. HOLY CRAP! The amount of forward pressure required to compensate for a complete engine loss was much more than I had expected.

I started the procedure again, but this time with a slightly less aggressive climb: That first one was a tad too exhilarating. Again, at about 200 feet, I pulled the throttle back and pushed the nose forward. And once again, I started to see the airspeed bleed, so I had to keep pushing to keep it stabilized. With the runway coming at me fast, I had just enough energy to flare and plant the plane. Again…HOLY CRAP! I had the pattern to myself so I kept repeating the exercise, slowly lowering my engine fail height to 100 feet, then 50 and finally 20 feet, where I could finally feel the cushioning of staying in ground effect. Now it was more like an aborted takeoff. This felt more routine.

So what did I learn from this exercise? I learned that before this practice, I would not have been ready if this event had happened in real life. What was really surprising to me was learning that even when I was fully expecting an engine out, my reflexes for doing what needed to be done were sluggish and timid. It took the entire training session to get my mind and motor skills tuned to the required response. And I didn’t quit until I felt confident I could and would do the right thing if something happened unexpectedly. But that was mid-season last year.

Locking in those Instincts

This season, I decided that besides getting out in some stiff crosswinds to keep up my proficiency, it would be prudent to do the engine-out kill-proofing drill again. Spring is always a good time to remove the rust.

I picked a windy day when I again pretty much had the airport to myself, except for the tower controller. I taxied to the long, 9000-foot runway to give myself maximal options for practice—multiple up-and-downs for each pass—then ran myself through a mental checklist to verify I was ready. Like the ski-racers and snowboarders at the Winter Olympics, I mentally rehearsed the maneuver at the threshold. I pulled the stick back for the climb, imagined the engine losing power and pushed the stick forward. When I’d run through it a few times, I was ready to try again.

When I was cleared for takeoff, I rolled out to the runway. I climbed 200 feet, chopped the power, dove, flared, recovered. Then I took off again, climbed 100 feet, chopped power, dove, flared, recovered. Then I did it again, climbing to 50 feet—lather, rinse repeat—keeping my airspeed at VX to VY the whole time. Each time, the change in view was horrifying. Going from a face full of blue sky to staring at concrete was just as I remembered, surprisingly ugly. But the training came back and my increasing confidence proved the exercise’s value.

See For Yourself

The next time you are at an airshow, fly-in event or where folks are demonstrating aggressive, high-angle takeoffs requiring full power, ask yourself what it might look like if the engine stopped. Better yet, get out there and see if for yourself. Take your time and don’t be overly aggressive with your training: You don’t want to become a victim, but you definitely want to ensure you have the correct response wired into your brain and muscle memory.

Pushing the nose down after an engine loss is critical. If you are barely above the ground, it has to be quick. It isn’t easy and it takes some practice. Before you practice though, do ATC (or other ramp-side witnesses) a favor and share your intentions.