I frequently glance at sidebars to gauge the depth/value of an article before reading the piece itself. As a round-engine pilot, I got a chuckle out of the first item in the “Don’ts” list (“Preflight Inspections,” November 2011). “Don’t rotate a propeller. Ever.” Really? If you are talking about a round engine and you want to destroy it, that advice works. If not, you might want to check for hydraulic lock by rotating the propeller enough to make sure all cylinders go through at least one compression stroke before you attempt a start.

Ernie Betancourt,

Via e-mail

288

Thanks, Ernie. We’re smacking our foreheads on that one. We should have distinguished between flat and round engines. Look for a related article in the near future.

Engine-Out Practice

I greatly enjoyed Tom Turner’s comprehensive and well-rounded discussion of what to do when your pride and joy becomes a glider (“Making The Field,” October 2011). The only advice I can add is “practice, practice, practice.”

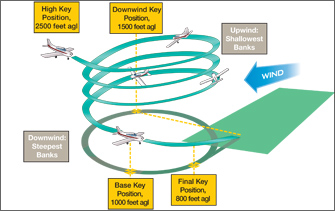

As an initial cadre F-16 driver, we were required to log six practice simulated flame-out (SFO) approaches—a 360-degree turn to landing from 8000 feet above the field—every six months. Touch-and-go landings were limited to initial checkout training only, so “practice” SFOs were never to touchdown.

Initially, we had a 100-foot minimum altitude for the go-around. Experience showed the last 100 feet of the very dynamic transition from a 180-190 knot, 10-12 degree glide to a 130-135 knot “normal” touchdown to be the most difficult part of the event. “First time” touchdowns under emergency conditions (typically, engine still running following an airborne engine anomaly) were usually anything but graceful, with many resulting in long, hot landings, hot brakes and occasional brake fires. The rules were quickly changed to state “no touchdown” and the long-landing/brake-fire scenario faded into history.

A few years into the program, I was giving a check flight in an F-16B when we experienced an engine stall (momentary reversal flow through the compressor) so I headed back to the base for an SFO to a full stop landing. The touchdown was a classic “grease job” at the computed touchdown speed, and the 1000-foot marker. The intercom comes on and I hear, “You have been doing this too much.”

211

Practice, practice, practice! I suggest every pilot should establish a self-imposed “requirement” to practice an engine-out approach at least once a quarter.

Col. Larry Danner, USAF (Ret),

Via e-mail

Risk Vs. Danger

I read with interest Bob Wright’s recent articles on training reform and risk management, and the ensuing reader mail (Unicom, November 2011). I’ve enjoyed the exchange, but think people are still missing an important point on the subject: Identifying, assessing and mitigating risk are not new and have always been taught. Every pre-flight incorporates these three items and always has; every decision to launch does, too. Every time a pilot looks at weather prior to flying, he is doing all three.

Sure, we do it badly as a group. And, sure, I would like to see certain components of risk be more visible in training, but I don’t think that is the essential problem. Scenario-based training is probably better than what most of us had, but the real world will always be uglier and more variable than anything we would encounter in training. So, while worth pursuing, it will be quite limited in its impact overall. Instead, I think it is most important to view risk from the proper perspective.

First, we need to distinguish clearly between inherent and operational risk; then we need to distinguish clearly between risk and danger. We can’t make any progress until we get that settled. With that out of the way, we need to invert our thinking when trying to avoid cumulogranite. When a pilot crashes, in contrast to conventional thinking, he typically is not taking something inherently safe and killing himself by doing something unsafe (obviously, stupid pilot tricks do not count here). Instead, he is taking an activity that is inherently unsafe and unsuccessfully managing the inherent risks.

Put differently, now we teach that we’ll live to fly another day if only we don’t do anything dumb. Instead, I would teach we should assume on each flight you are going to die unless you manage the inherent and operational risks properly. That’s a big difference and one critical to how we go about imparting some wisdom to fellow pilots. But few of us think the latter way.

Hopefully food for thought as you have others continue to write on the subject. My few articles on the subject have been a tiny voice lost in the wind. But you have a great platform to keep pounding home the good points.

Jeff Schweitzer,

Via e-mail

The letter writer is a frequent contributor to this and other operations-oriented aviation publications.

288

I’ve read with much interest and some concurrence the articles on risk management and mitigation, but I don’t see discussed or emphasized what I believe is the most important factor in this whole approach: the inner nature of the individual pilot and instructor with respect to how they see the same risk situation.

Different people see the same risk very differently. Some either consciously or subconsciously will see risk as a challenge—“Let’s do it!—while others won’t touch the situation. Yes, to a degree this is an innate characteristic based on personality, background, age, maturity, experience, judgment, discipline and host of other factors.

The new concept for teaching risk management is okay, but is centered on empirical exercises designed to reach a go/no-go decision. I just don’t see too many pilots figuring out these exercises, either in the cockpit or at the FBO.

The real challenge is how to size the new risk-management training to reach the individual pilot’s inner thought processes. And, yes, the CFI’s, too.

Thomas W. Hall, II,

Clarkston, Mich.