As a pilot gains ratings and experience, he or she usually transitions to bigger, faster and more capable aircraft. Progress quickly enough to aircraft with enough bells and whistles in them and its easy to become impressed with all the capabilities at your fingertips. Equipment like airborne weather radar, approved de- or anti-icing and two powerful engines translates into an almost-all-weather airplane. With all that capability eventually comes a desire to use it in the belief the aircraft was designed to reliably detect and avoid anything Mother Nature can throw at it. And then, every now and then, someone discovers no airplane is bulletproof, and no pilot can handle everything, either.

With all the bells and whistles working as they should, its easy to sit back and adjust a heading bug here, insert a new waypoint into the flight plan away from the weather and motor off to Point B without having to give it too much thought. You might even adopt a rule of always going through the green and yellow stuff but avoiding the orange and red.

Thats an aggressive plan, and better than nothing. But what if the airplanes also carrying some ice, so that its heavier than it should be and stalls at a lower angle of attack? Still want to go banging through that green and yellow area in front of you, the one on the display that hasnt been updated in maybe 20 minutes? When was the last time you practiced stall/spin entry and recovery aboard an iced-up twin turboprop in a thunderstorm? We thought so.

But thats pretty much what happened in an accident were about to describe, one involving a likely icing encounter followed by thunderstorm penetration. The results were predictable, even if the pilot failed to use all those bells and whistles to see them coming.

Background

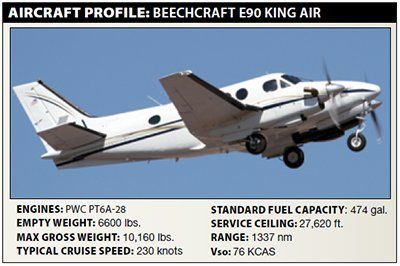

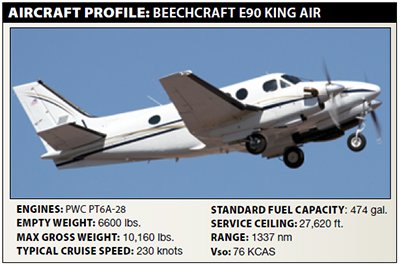

On December 14, 2012, at about 1805 Central time, a Beechcraft E90 King Air impacted terrain following an in-flight break-up near Amarillo, Texas. The commercial pilot and passenger were fatally injured. Instrument conditions prevailed; an IFR flight plan had been filed to Fort Worth, Texas.

The area forecast for the Texas panhandle area, issued at 1345, included scattered clouds or a broken ceiling at 8000 feet msl, tops to 15,000 feet msl, widely scattered and possibly severe thunderstorms, and cumulonimbus tops to FL350.

A review of ATC communications and radar data revealed the airplane had been cleared to FL210, and to deviate east of course for weather and traffic avoidance. Shortly thereafter, the airplane appeared to turn to the north, and the pilot did not respond to the controller’s query about the turn. Radio and radar contact subsequently were lost.

Investigation

The wreckage was found about 20 miles south of KAMA on open, rolling land. All major components of the airplane were accounted for. The airplanes outer wing sections, engines, elevators, and vertical and horizontal stabilizers were separated from the fuselage and located in several directions from the main wreckage, strong evidence of an in-flight break-up. All of the examined fracture surfaces exhibited features consistent with overstress failures, with no evidence of fatigue. Control-cable separations were also consistent with overload failure.

Radar data showed the airplane departing and climbing away from KAMA. The airplanes track depicted a gentle S-type turn as the airplane headed in a southerly direction. The last several radar returns had the airplanes altitude at 14,700 and 14,800 feet msl, before the airplane entered a right turn. The airplane descended from 14,800 to 14,600 feet as the turn continued; then dropped to 11,200 feet before the altitude data ended.

Two Airmets were active at the accident location; one advised of moderate turbulence below FL180 and the other surface greater than 30 knots. Several convective Sigmets also were valid at the accident time and location. Regional Nexrad weather radar depicted a north-south oriented line of high (>50 dBZ) reflectivity values east of the accident site in western Oklahoma. Only light reflectivity values were depicted near the accident location.

The relative humidity was greater than 90 percent between about 11,000 and 13,000 feet msl, with the freezing level at approximately 8400 feet. Assessments noted the potential for moderate clear icing around 12,700 feet, with a potential for light mixed and rime icing at altitudes between 10,700 and 13,500 feet.

An on-board EGPWS unit recorded 22 seconds of information during the airplane’s descent. During the right turn, the airplane descended from 13,966 feet to 5904 feet. The airplane’s descent rate was over 18,000 fpm and, after 19 seconds, the descent rate exceeded the EGPWS maximum parameter of 32,000 fpm.

Probable Cause

The NTSB determine the probable cause(s) of this accident to include: The pilots loss of control of the airplane after encountering icing conditions and heavy to extreme turbulence and the subsequent exceedance of the airplanes design limit, which led to an in-flight breakup.

Its not known for certain that the accident airplane encountered icing, nor at what intensity. But its a good bet the pilot stumbled into a building storm after he picked up a bit of the icy stuff and got busy trying to shed it. Well never know exactly what brought down this airplane: Did the storms turbulence cause the loss of control, did the ice alone do it or did the two act in concert?

We also dont know what the pilot was seeing, or how. We dont know, for example, if he was using airborne weather radar in addition to the installed Nexrad display capability, both or neither. Its also not clear from the record if the pilot obtained a pre-flight briefing or what it may have contained. Lots of unanswered questions.

We further dont know what made the pilot lose control. But a good takeaway from this accident is that even an almost-all-weather airplane like a King Air can find conditions its pilot cant handle. Thats actually true for any airplane-theres always going to be some weather it cant handle, even if everything else long ago was secured in a hangar.

Many of us likely will feel somewhat bulletproof by the time we move up to a twin turboprop. Unless we treat the airplanes additional capabilities as even better tools with which to avoid poor weather and icing, were destined to misuse them.