Overall, I think “Engine-Out IFR Approach” (April) provides some good advice on the topic. Additionally, its a good mental exercise to go through on the ground prior to a flight-sort of a what-if scenario. However, there are a couple of things that I was surprised were not discussed and which would make the approach even easier. 288 The author states that you should fly some “approximate heading” until “the position of your airplane on the moving map and extend the runway with your own imaginary line.” The GNS430/530 provides two easier methods of determining a runways extended center line. One method is to press the CDI button, then spin the OBS to 220 (the desired heading to the airport). The second method is to press the “Direct” key, then press the cursor button and move the field at the bottom right (CRS) and enter 220 for the heading to the waypoint. Either method will provide you with an extended center line. You can fly to that line and turn final with no mental calculations or guessing when some imaginary line is lined up with the runway. As a side note, I use this feature on virtually every night VFR flight for orientation as well. Keep up the good work! Brad Johnson Via e-mail A couple of years ago, a close friend and pilot with whom we were flying asked how long it took to learn the GNS530 in our panel since 2000. We responded, “Were still learning it.” You (and the other readers who pointed out this time-saving method) are absolutely correct that it is a great way to orient the airplane and the runway. But not everyone is fortunate enough to be flying with a GNS430/530, and we were trying to make the instructions a bit generic, for other moving map navigators, including handhelds and portables not specifically designed with aviation in mind. Which Command? Regarding the pitch or power discussion in your February issue, I see various contributors have different views. Ray Leis says pitch for altitude and power for speed, then cites autopilots with auto-throttle control. Rich Stowell says, “pitch for airspeed and power for the altitude” in his excellent article on landings, and Tom Turner wrote in his article, “Stabilized Approaches,” says, “On reaching the MDA at the trimmed airspeed, add power to maintain level flight.” All this reminds me of a November 2005 article, “Flying Slowly.” In it, author Tom Oneto makes many points with which I agree. On the other hand, I part company with him when he invokes the regions of normal and reversed command. I have been flying for 43 years-I learned to fly outside the U.S.-and that was the first time I ever heard the concept of “reversed command.” This strikes me as an overly complicated description, serving only to obfuscate. It does not inform pilots how to determine they are in that mode and what they should actually do about it. If pilots have to pause to contemplate whether they are in reverse-command territory, the game is already over. I also think that he does us a disservice when he trots out the fuzzy and often abused term, which by itself means nothing. Too bad he used it for the title of the sidebar on power, lift and drag, that explains (correctly) why we need ever increasing power to maintain altitude as airspeed decays. Whats misleading about the normal/reversed command arguments is not that the lift/drag diagram is wrong; its that there is an implication that the real-world aircraft control input requirements are different at speeds above and below the total drag minimum on the graph. The point that I am surprised that he does not make is the one rule that the pilot needs to keep in mind as the guide for controlling slow flight (or cruise flight for that matter): Pitch is the primary control for airspeed, and power is the primary control for altitude. There is no sub-sonic mode of flight that I know of where this is not true. 288 Fly level at one knot over the stall speed, and reduce power without moving the elevator, and the aircraft will sink, and probably stall as the angle of attack increases to the critical angle in the descent. Even if I stall, I push the stick forward immediately to increase flying speed, and add power to arrest the descent. If I am cruising level at 165 knots, I can climb by adding power, and controlling the airspeed with pitch. If I am racked over in a 60-degree bank, and need to maintain altitude, I have to add power. Once this is understood, the coordination of pitch for speed and power for altitude will always make sense. This works in level flight, in turns, and when climbing and descending. The concept is especially useful for understanding how to manage a prolonged descent on an instrument approach, but there is no reason why a VFR pilot cant make use of the same basic control concepts on the tight descent over water into the short field with the great restaurant. Then the only reverse command necessary is refusing another piece of pie. Dave MacRae Princeton, N.J. The FAAs excellent publication, “

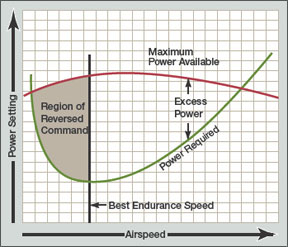

“Flight in the region of reversed command means that a higher airspeed requires a lower power setting and a lower airspeed requires a higher power setting to hold altitude. It does not imply that a decrease in power will produce lower airspeed. The region of reversed command is encountered in the low speed phases of flight.

“Flight speeds below the speed for maximum endurance (lowest point on the power curve) require higher power settings with a decrease in airspeed. Since the need to increase the required power setting with decreased speed is contrary to the normal command of flight, the regime of flight speeds between the speed for minimum required power setting and the stall speed (or minimum control speed) is termed the region of reversed command.

“In the region of reversed command, a decrease in airspeed must be accompanied by an increased power setting in order to maintain steady flight.”

At left, weve reproduced the FAAs graph depicting this area of the flight envelope. Additionally, well have a feature-length article on this topic in a subsequent issue.

Up Is Down

The sidebar in “Mellow Yellow” (March) on airspeed indicators and V-speeds raised some questions.

For instance, how did the FAA come to certify an instrument that appears to be upside down? The needle progresses right to left, opposite a speedometer. Also, the bottom of the white and green arcs are at the top, and the top of the white and green arcs are at the bottom.

Im sure more than one student performed mental gymnastics to wrap their mind around this. Perhaps the words “start and end” should replace “bottom and top?”

Just a thought…

Tom McMullen

Via e-mail