By Ken Ibold

There are a lot of pilots who dont fly as often as theyd like to, for reasons ranging from cash shortages to lack of time to unreliable airplanes. There are also a lot of pilots for whom that lack of flying translates into a lack of proficiency, even if they meet the legal requirements for flight.

Many are the temptations that lead pilots to make flights for which they may be in the clear legally but behind the eight-ball practically. Some of them have to do with ego, sure, but other times the pilot is a poor judge of how much those hard-won skills have deteriorated.

Conscientious pilots try to stay on top of this phenomenon and opt for practice when their regular flying does not expose them to the kinds of circumstances that keep them sharp. But even practice, if done halfheartedly or improperly, may not do much good when the chips are down.

An illustration of this dynamic is the last flight of a pilot who launched his turbocharged twin, a Piper Seneca, from North Myrtle Beach, S.C., to Oxford, Conn., one April evening. With full fuel and an IFR flight plan, the pilot embarked on a three-hour flight home.

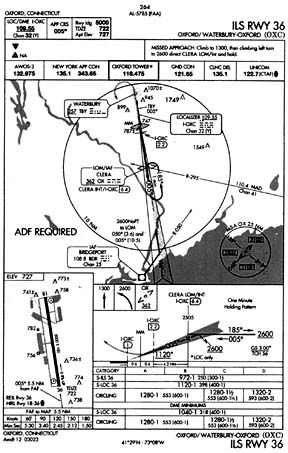

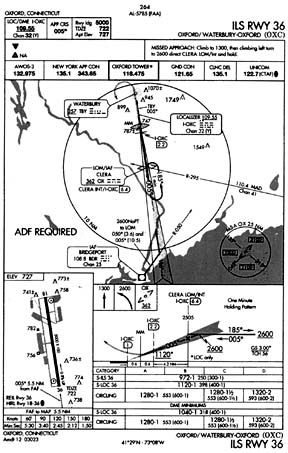

The flight proceeded uneventfully into the New York Terminal Radar Approach Control area, and the pilot got vectors to intercept the localizer course for the ILS Rwy 36 approach into Waterbury-Oxford Airport. Weather at the time was wind from 200 degrees at six knots, gusting to 15, visibility two miles, ceiling 300 feet overcast, temperature 52, dewpoint 51. This approach was anything but a slam-dunk.

At 9:02 p.m., the pilot advised the approach controller that he was established on the localizer. Five minutes later the controller cleared the pilot for the approach. At 9:14, the approach controller told the pilot he was about two miles from the outer marker, Clera intersection. The controller terminated radar service and approved a frequency change that would put the pilot on the airports frequency.

The pilot acknowledged. It was the last radio communication he made.

A witness who was standing in his driveway facing the airport heard the airplane approach. When he looked up, the Seneca flew over his house about 40 to 50 feet above the trees. It appeared to be flying at a constant altitude. The witness said he saw the airplanes landing lights illuminate the treetops as it crashed into the woods.

Other witnesses said the sound of the aircrafts engines revved just before the impact.

Long and Winding Road

Radar data for the airplanes flight path could not be retrieved due to a technical malfunction with the FAAs recording equipment. But in combing the wreckage, investigators came across a Garmin GPSMAP 295 that had recorded the entire flight.

Examination of the last four minutes of the flight track showed that the airplane was at 3,008 feet msl (GPS derived) when it was about 1.75 miles south of the outer marker. It turned left and passed abeam the maker, about a mile left of course, at an altitude of 2,837 feet. It then turned right and momentarily intercepted the localizer course, then turned left and flew about three-quarters of a mile left of course. The pilot then turned back to the right, crossing the localizer course at about 1,271 feet msl just south of the middle marker. Then the airplane drifted left, back toward the proper course, just before the data ended. The altitude then, 2,000 feet southeast of the runway, was 779 msl. The airport elevation is 727 feet msl. The airplane came to rest at 650 feet msl, some 325 feet below decision altitude.

Legal vs. Smart

In its finding of probable cause, the NTSB blamed the pilots failure to follow the published instrument procedure. It cited night conditions and a 300-foot ceiling as factors in the crash.

While such findings of official fault may fly in Washington, analysis of the accident investigation reveals clues other pilots can put to use in their own cockpits.

The last entry in the pilots logbook was more than four months earlier. At that time, the pilot had accrued 897.5 hours, of which 341.2 were in multi-engine airplanes, 119.7 were at night and 45.2 were in actual instrument conditions. The logbook also showed the pilot had executed the ILS Rwy 36 approach into Waterbury-Oxford Airport eight times in the previous six months.

One other record of the pilots flight activities was found. On a separate piece of paper he recorded two separate flights he had made two weeks earlier. The first flight was for one hour and the pilot wrote that he had completed turns, ILS 36 circle to land RWY 18 … 3 landings. Later the same day, he logged 1.7 hours and remarked that he had flown turns, 3 landings day, 1 ILS 36.

It is unclear whether he flew the approaches under instrument conditions, flew them in visual conditions with a safety pilot or flew them in VMC.

The pilot had logged enough to legally file and fly IFR. He had logged landings for day currency, although his night currency is unknown. But had he done enough to ensure he was proficient in addition to legal? The answers to that question are not so clear.

Although a Seneca is, by twin standards, a fairly docile airplane, it still requires an absolute level of proficiency to handle – especially when a routine flight becomes non-routine.

The impact damage shows the airplane was carrying a lot of energy when it hit the trees. The flaps were extended 10 degrees and the landing gear was down, consistent with a routine instrument approach. There were no indications the airplane had suffered an engine failure.

In fact, the wreckage contained only a single indication that the final moments of the flight might have been unconventional in any way.

The cockpit had fragmented such that the altimeter, airspeed indicator, turn coordinator and directional gyro were outside the main wreckage. When the directional gyro was examined, the gyro was intact but the housing did not display rotational scoring, which may be considered evidence that the gyro was not spinning at the time of impact.

The vacuum pumps could not be examined, due to fire and crash damage, but the wreckage appeared to indicate the vacuum pump drive couplings had not sheared, which they are designed to do when the pump fails.

Painful Lessons

Given the pilots uncertain proficiency, one might be tempted by hindsight to question whether he should have attempted the approach at all, given the low conditions and the gusty tailwind. However, there are some lessons that every pilot can take from this kind of accident.

The pilots difficulty in tracking the localizer inbound should have alerted the pilot to the potential for trouble. It also should have reinforced in him the need to stay at or above the published glidepath, as he was already cutting the margins.

The FAAs practical test standards for checkrides essentially say the examiner should not see any maneuver in which the outcome is in doubt. This is a good rule to live by, not just on a checkride, but any time.

If you are having trouble tracking the localizer, abandon the approach early, settle down and then either try again or go elsewhere.

Its easy to envision the localizer intercept problems stemming from a dying directional gyro in the accident in question. Whether that was a root cause is moot. But it does raise a caution flag for pilots who might be tempted in the future to push on, when neither their past nor present bode well for their future.

Also With This Article

Click here to view “Aircraft Profile.”