In another forum, I recently complained that much of the technological advancement the general aviation industry has seen in my flying career manifests itself only in the instrument panel, not in the airframe or the powerplant. The evidence supporting my complaint is rather abundant, and my own airplane—manufactured in 1966—is something of a poster child.

While it has ADS-B Out, a WAAS-enhanced GPS navigator, an autopilot, a digital engine monitor and assorted other devices not available when it rolled out of the factory, it’s still basically a hand-made, all-metal airplane powered by engine technology dating from the 1930s. No amount of upgraded upholstery or a fancy new paint scheme can hide for long the fact it’s usually older than the passengers I carry. That I can buy a new copy of the same basic airplane is more evidence. Why haven’t the advances in materials and powerplants trickled down to personal aircraft?

In response, a few people took me to task, pointing out the advances incorporated into the Cirrus line of piston singles, or the designs available from Diamond Aircraft. Also, they reminded me of the innovation present in the experimental aircraft community and even in factory-produced light sport aircraft. And powerplants are undergoing some changes, they pointed out, including offerings from Rotax but also including diesels and, increasingly, electric-powered aircraft.

Those and other developments certainly are noteworthy. And it’s probably too much to ask—and too expensive—for an engine to be dropped into my airplane offering more power and reduced fuel consumption. The airframe is the airframe, of course, and even if a set of new, carbon-fiber wings or other components were available, they’d probably be too expensive to consider.

After some introspection, I realized the source of my frustration: drones. Here’s an entirely new product category designed to do at least some of the same things as my 1966 airplane, but incorporating the latest advancements in materials, power and flight control. The darn things are as cheap to operate as recharging my cellphone while flying autonomously along a predefined route. Yes, it’s an apples-and-oranges comparison and no, they can’t haul 1000 pounds of people and luggage to the ski slopes, but that day may come.

When it does, that new generation of personal aircraft likely will include technologies designed to prevent accidents. Things like envelope protection, where the machine doesn’t allow its pilot to put it into an unsafe situation. Technologies like GPS and ADS-B are a given, along with a networked operating environment where it and all other nearby aircraft “talk” to each other to manage collision avoidance, sequencing and efficient routing. Operator certification won’t be nearly as complex, time-consuming or expensive as it is today.

When that happens (not if), personal aviation will finally realize its “flying car” promise, but all the fun and sense of accomplishment gained by actually flying an aircraft will be missing, thanks to the automation. I can wait.

Meanwhile, we’re coming up on the two-year mark before ADS-B equipment is required in certain U.S. airspace where only a Mode C transponder is needed today. January 1, 2020, will be the culmination of a decade-plus of implementation by the FAA and equipment installations by owners and operators. Of course, that won’t be the end of the story.

For one, it’s safe to say not every aircraft with the potential to fly in airspace where ADS-B will be required will have the technology on the first day of 2020. (Controllers are empowered to waive the requirement the same way they can today for Mode C. It will be interesting to see how flexible and accommodating ATC is with its waiver authority.)

Another reason ADS-B will continue to be installed after the deadline is there likely won’t be sufficient shop capacity to perform all the installations demanded by then. While it might be inconvenient for some operators, it’s not the end of the world, and they’ll eventually get their gear. Some people will wait until the last minute—or beyond—hoping to get a lower price on better equipment or to take advantage of suddenly reduced demand and costs for installation. That may or may not be the smart play.

Right now, I’d guess the new requirements will go into place with a whimper, not a bang: There will be little fanfare or angst when the deadline comes and goes.

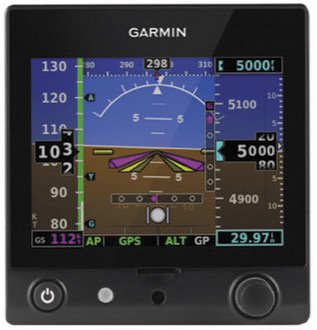

Meanwhile, attention will turn to whatever the next big thing will be. From where we sit at the end of 2017, it appears revised FAA certification standards and healthy competition among manufacturers will combine with other factors to continue the ongoing modernization of what I’ll call legacy instrument panels, like the one in my 1966 airplane. It already is economical to put in a couple of display screens offering primary flight information and replacing my traditional round gauges. Other electronic gizmos and their automation will bring enhanced capabilities and greater reliability. Higher useful loads will be seen as vacuum pumps and associated plumbing are eliminated in favor of a few wires.

But we’ll still have a few chowderheads who lose control after they get into weather over their ability or when they botch an impromptu fly-by to wave at their girlfriend. Even as we lever technology into the panel, there still will be a loose nut behind the wheel. In other words, we’ll still need to concern ourselves with safety and the things we can do to enhance it: training, risk management and good maintenance. Job security is a wonderful thing.