-by Ken Ibold

Flight plans come in two flavors: VFR and IFR. GPS units carry one of two designations: VFR or IFR. Weather is either VFR or IFR.

While VFR and IFR appear to be black and white concepts, there is one area where there are so many variations that generalizations become dangerous: calling an aircraft IFR-equipped. The issue comes up routinely in the ads for airplanes for sale. A vintage trainer may be called King IFR equipped, thereby suggesting the airplane is ready to do serious battle against the elements.

But in fact, the IFR equipment that goes into an airplane dictates what missions that airplane is capable of just as certainly as do the capabilities of the pilot who climbs into the left seat. While pilots are used to assessing their skills from the standpoint of experience and proficiency, many forget that the airplanes IFR equipment must also be evaluated for redundancy, capability and comprehensiveness – because all IFR airplanes are not created equal.

Serious IFR pilots flying well-equipped IFR airplanes in hard-core instrument conditions know what is expected of them, but more casual instrument pilots flying lightly equipped airplanes under instrument rules face a broad range of challenges brought on by the limited options they have.

Shades of Gray

When it comes to avionics stacks, many pilots drool over color moving maps, approach-approved GPS, autopilots with altitude preselect, weather uplinks, radar and collision avoidance gear. Unfortunately, reality sets in somewhere short of the ideal because of the staggering price – in dollars, panel space and weight – that installing such comprehensive equipment represents.

Renters dont have a choice. They fly the airplanes that are available to them. Owners dont really have a choice, either. They fly the panels installed in their airplanes. And those panels can be sparse, indeed.

To fly under instrument flight rules, FAR 91.205(d) says the airplane needs VFR equipment plus two-way radio communications, navigational equipment appropriate to the ground facilities to be used, needle and ball/turn coordinator, sensitive altimeter, clock, artificial horizon, directional gyro, and a sufficient generator or alternator to power the stuff.

Nowhere in Part 91 does it say the airplane has to have dual nav/comms or an audio panel or an ADF. It says nothing about pitot heat or vacuum systems or GPS. According to the regulations, a pilot can embark on a coast-to-coast trip in lousy weather armed with nothing but a basic panel of gyros and a creaky old comm with a single VOR or ADF. It may not be smart, but its legal.

Note that a state-of-the-art IFR certified GPS doesnt count unless it also includes alternate means of navigation, meaning VORs or NDBs. You dont have to even turn them on if the GPS has RAIM, but they have to be installed and they have to work.

Flight Planning

Any flight requires planning, but flying with minimal IFR equipment is made more difficult by the limited options you may be presented with in some situations. Weather and aircraft range must be considered, as in any flight, but you must also consider alternates that meet the weather criteria as well as have the kinds of instrument approaches for which youre equipped. Realize that some approaches will be off limits if you dont have DME, for example.

One of the greatest risks you take flying in instrument conditions with minimal equipment is what happens if something fails. And were not talking here just about a nav radio giving it up. Ground facilities go off-line sometimes – both for Notamd maintenance and because of equipment failure – and youd better know your options if that happens.

Because so much will be riding on the equipment you do have, maintenance becomes even more crucial. The trouble is, avionics are notorious for crapping out without warning. There are often some warning signs, however, so keep your eyes and ears peeled for indications your gear is going down, and take some pre-emptive action.

Most of all, make sure your decision-making mindset is in line with the risks and the conditions involved in the flight. With this kind of instrument flying, a gotta get there mentality wont cut it if conditions are much less than marginal VFR.

Visibility, ceilings and convective activity all become more potent adversaries if your arsenal of instruments is small. Dont forget that fact, and dont forget the fact that, if all you have is an ADF, youd better be pretty good at shooting NDB approaches.

Enroute

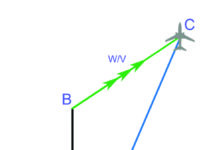

Finding your way from point A to point B is the most basic of instrument skills – and one thats been made even easier since the advent of GPS. But filing and flying direct gets more difficult with minimal equipment. Legally, IFR navigation means the ability to use VORs or NDBs, since even IFR GPS receivers cannot be your sole source of navigation.

The FAAs official position is that handheld and VFR-only panel mount GPS units cannot be used for IFR navigation, except in an advisory capacity. That said, general aviation pilots routinely file and fly direct based on VFR GPS units. Just tell the controller youd like a vector direct to your destination 300 nm away and they get the hint. Often youll get a clearance for that routing – or something close to it – if youre under radar service.

However, navigating low-altitude airways is a different story. While navigating from VOR to VOR is easy enough even with one nav unit, be prepared for some quick flipping between frequencies if one of your fixes is an intersection and the winds are strong. This is where the situational awareness of a GPS comes in handy. Use the GPS as one of your navigational tools, occasionally verifying its accuracy with your one VOR receiver.

Its probably also safe to assume that if the airplane is marginally equipped for IFR it does not have an autopilot. While an autopilot is not necessarily an essential piece of IFR equipment, you must consider the impact not having one will have on your workload and fatigue, especially if flying single-pilot.

Its also likely that such an airplane does not have any kind of weather detection equipment other than the pilots eyeballs. With only one comm, its essential you talk to the controller to leave the frequency, since you wont have the option of monitoring another frequency during lulls in the controllers voice.

FlightWatch is your friend on such a flight. You may have to forego such niceties as monitoring ATIS broadcasts en route, depending on the airspace and how busy the radio is.

While youre legally within your rights to make the flight, you are particularly vulnerable to loss of nav and/or comm signal and should brush up on the regs concerning your options and responsibilities in such circumstances. From a practical standpoint, have a VFR option if you lose your navigational ability. Plunging onward with your emergency handheld GPS or transceiver is probably not the best option.

Approaches

Once you get to your destination, the approaches you can fly may be more limited than you think. If, for example, your airplane has a VOR receiver with localizer and glideslope, you may be tempted to shoot an ILS into your destination.

Fair enough, except you may not be able to. For one thing, many ILS procedures require an ADF because the missed approach uses an NDB for the holding fix. Planning to fly a VOR approach? Watch out for those that require DME to define step-down fixes. And what if the approach you need to use goes against the airport traffic using a different kind of approach to a favored runway? Be prepared for some lengthy delays before making a downwind approach to a potentially challenging circle-to-land.

While youll identify many of these factors as part of your preflight planning, the fact is that weather at your destination is never a certainty until you get there, and by taking the trip in the first place you have accepted the fact that you will face severely reduced options.

Even if everything works perfectly, you should still anticipate a healthy amount of OBS dialing. While many VOR approaches are straightforward and involve little other than dialing in and tracking a radial, others rely on cross radials from other stations to identify stepdown fixes. Here again is where a non-IFR GPS can assist in your situational awareness by letting you know when you get close and allowing you to monitor your progress more closely.

Missed Approaches

When you miss an approach with your sparsely populated panel, you learn one reason why serious IFR requires more comprehensive equipment.

When planning the flight, analyze what situations may arise that would force a missed approach. If the weather goes below minimums, know your options ahead of time – both at your filed alternate and any other nearby alternates where you might have a chance to get in.

For example, if youre flying a VOR approach and cant get below the clouds, you ought to know if perhaps the approach you just made has a higher MDA than other nearby VOR approaches because of terrain, ground obstructions or some other TERPS criteria. If so, a similar approach to a nearby airport may save the day. If not, you had better be ready for your alternate and the weather there had better be acceptable.

The same rationale applies if your destination airport suffers a VOR outage or some other equipment failure. If all youre equipped for is a VOR approach, it wont do you much good if all the airports around you have only NDB approaches. This is another aspect to cover in preflight planning. You may even want to outline airports along your route of flight that have approaches for which the aircraft is suitably equipped. Flying single pilot in weather with no autopilot is no time to be rummaging through charts and approach plates.

Backups

With a light avionics load, the question of backups is simple to answer: There arent any.

If that doesnt make your heart start pounding, you can assume youre cut out for this task.

Actually, thats not quite true, because you always have some options. If your nav unit goes out or the airports hardware fails, the controller can give you a surveillance approach – essentially vectors to the runway. If your comm radio fails but you can still navigate, you can follow lost comm procedures and carry on with your clearance.

Problems arise if you lose both. Lets say youre flying with a King KX-155 as your only nav/comm and it decides to give up the ghost. Now youre officially blind and mute. Your preflight planning did enlighten you as to where VFR conditions exist, right? Use your emergency authority to find yourself a VFR airport to get repairs.

ATC will keep everybody off your tail – although in the current environment maybe theyll scramble an escort for you so you can be sure youll find an airport.

A much less stressful way of finding the airport would be to whip our your handy-dandy portable GPS and let it point the way. In most cases, the handheld should be used to get you to visual conditions.

There may be the occasional circumstance in which pressing on with a handheld GPS for guidance may be preferable to bolting for VFR, but as a general rule it doesnt seem like a good idea. If you were already established on a localizer course in flat country with moderate ceilings when the only VFR conditions were a hundred miles away, it might make sense to go ahead and use the extended runway centerline indication on the handheld for a few miles. Might want to alert the controller, however, so there will be another set of eyes on your course.

A backup transceiver is of less certain value, particularly if there is no external antenna connected to it. Using only the portable antenna, communications are scratchy from any distance and trying to use the VOR/LOC features is challenging at best.

In these cases, the best backup you can have is a Plan B that gets you into the least challenging conditions you can find.

Maintenance

Avionics maintenance is something of a black art, but its one you must practice if you have everything hanging on one box of circuits. If you make such a commitment, make sure youre working with quality gear.

If your CDI flags at random times until you smack the glass face with your knuckle, it might be trying to tell you its not up for a solo cross country. If your comm radio dies on the 16th of every month while youre taxiing out, you might want to look at it before you launch to your sons college graduation ceremony on the 12th.

If controllers say your communications are scratchy, and theirs dont sound good either, you should consider having your 15-year-old antennas checked for corrosion – and probably replaced.

In such an environment, maintenance by necessity has to become proactive rather than reactive. If something breaks, it may be too late. If you dont want the airplane to spend its life parked outside the avionics shop, consider overhauling the units you have, or possibly getting new ones.

If your minimalist panel is dictated by your budget, make your launch criteria conservative so you can deal with failures. If that panel is determined by physical space in the airplane, put in the best quality avionics you can afford. This is one area where money spent on repairs may be a false economy.

Decisions

Flying IFR with only a single comm radio and a single nav unit is like flying over the mountains at night in a single-engine airplane. You can do it legally, but to be smart about it you must limit your exposure to catastrophe by facing the risk squarely.

If youre flying IFR in clear skies, then the flight is no more dangerous than any VFR flight; you simply have the navigational and communications responsibilities of instrument flight. An avionics failure is essentially a non-event if you can revert to VFR and either complete your flight or divert for maintenance.

Likewise, punching through a broken cloud layer to cruise on top and descending through the clouds to a visual approach rather than spiraling down through a hole seems to carry an acceptable risk as well.

But as the weather scenarios close in, it ought to get harder to justify the flight. Your no-go decision in a lightly equipped airplane should come more quickly than in an airplane with a full complement of avionics.

Finally, make sure the pilot is up to the task. Can you handle flipping the VOR frequency back and forth while bearing down on an intersection, then holding there? The answer had better be yes.

Flying IFR with minimal equipment sounds uncomplicated and a little carefree – and it can be. But the true test of flying preparedness comes when things dont go according to plan. Thats when minimal equipment can turn to none in a hurry, leaving you to watch as the options close down around you.

Also With This Article

Click here to view “Detecting Failure.”

Click here to view “The Faces of IFR Panels.”