Single-pilot IFR (SPIFR) used to be a thing, back in the days before things like headsets, autopilots, moving maps and automated navigation became widespread. Journals like this one often carried articles urging pilots to pay attention to things like backup instrumentation, cockpit organization and fatigue to help minimize its risk. While these factors remain important, increased automation, improved procedures and charting, and training that recognizes SPIFR’s do-it-all imperative—among other evolutionary changes—have combined to make the practice much more prevalent and accepted today. But that’s not the same as saying the practice doesn’t merit special attention and consideration.

For one thing, SPIFR in simple airplanes like a Cessna Skyhawk differs greatly from the same operation in more complex airplanes. And more and more highly capable and sophisticated airplanes are joining the fleet, often designed and intended to be flown by a single pilot. As part of a renewed emphasis on their safety, light business aircraft (LBA) is a category created by the National Business Aviation Association (NBAA) to cover those of its members who fly piston, turboprop or turbojet aircraft of 12,500 pounds gross weight or less. Most of these aircraft are flown single-pilot by their owners, for whom piloting their LBA is incidental to their business activity. They could thus be described as non-professional pilots. However, the safety record shows that these aircraft must be flown professionally, regardless of how the paycheck is earned.

Through the Cracks

Until recently, the constituency comprising LBA operations was paid little attention by the major aviation organizations. Most general aviation pilots affiliated themselves with either the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association (AOPA) or the Experimental Aircraft Association (EAA). Most of those organizations’ members, especially in EAA, often do not fly for personal or business transportation purposes. The heavy-iron two-pilot corporate jets already were well represented by the NBAA. Meanwhile, the operational, safety and advocacy needs of single-pilot, high-performance aircraft and their operators were not being fully addressed.

That began to change during the period from 2000-2010 as the very light jet craze overtook the aviation community and as single-engine turboprops became increasingly popular. At the time, it was assumed by many that these aircraft would replace the aging fleet of piston and turbine-powered propeller-driven twins. That’s not how it’s worked out, yet. I would also add that the Cirrus phenomenon was also instrumental as this new state-of-the-art design showed how effective it could be as a transportation tool.

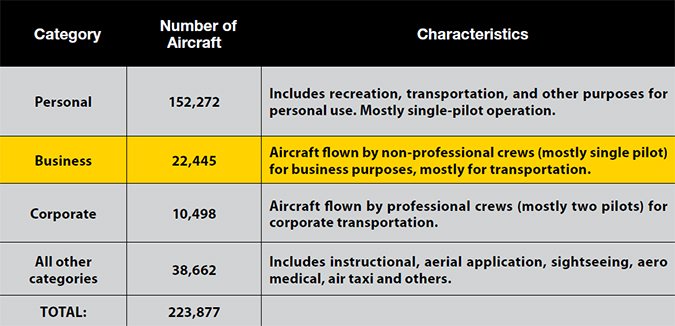

The bottom line is that there are a substantial number of general aviation aircraft that could be characterized as very high performance single-pilot transportation machines. The table at upper right presents a current picture of the general aviation fleet’s composition. It’s important to point out, however, that a good portion of the 152,000-plus “personal” aircraft are high-performance airplanes used for personal use and occasional business transportation. Their pilots are operating the same equipment over the same stage lengths and with the same “got to get there” external pressures as the pure business aircraft. I estimate that about 50,000 or so aircraft in the personal category fit this description. That suggests about 72,000 aircraft (22,000 + 50,000, or nearly one-third of the GA fleet) could be considered LBA and share the same operational and safety concerns.

Getting Attention

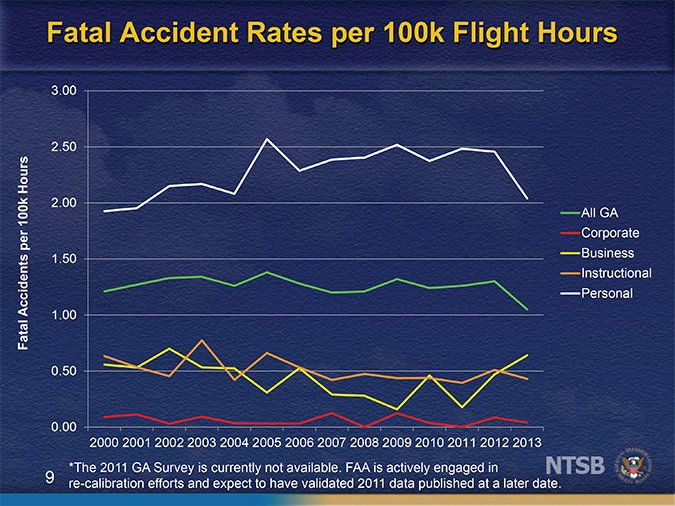

By the overall standards of general aviation, the single-pilot, high-performance business aircraft segment already has a good safety record. The chart below, from a recent presentation by NTSB Member Earl F. Weener and delivered at the NBAA’s Single Pilot Safety Standdown in November 2015, demonstrates this. Someone looking at this chart, however, might easily conclude business aviation single-pilot operations clearly must have major safety issues compared to their big brothers in the corporate world. The corporate accident rate, both fatal and non-fatal, in most years is comparable to that of the scheduled domestic U.S. airlines.

A couple of years ago I analyzed business aviation fatal accidents during the period 2006-2009. My search of the NTSB database turned up 40 business fatal accidents for this period. Only 34 of the files had enough information for me to determine how many of these could be considered to have poor risk management as a root cause, or not. That is, was the hazard and associated risk that resulted in the accident detectable by the pilot such that he/she could have identified, assessed, and mitigated the risk in a manner that the accident could have been prevented. I found that 24 (71 percent) of the 34 accidents met this test. I judged that three accidents were due to undetectable mechanical issues while only seven (21 percent) were caused by deficient “stick and rudder” or poor instrument skills. These findings were consistent with my other analyses that I have conducted on other general aviation populations.

Multiple LBA Communities, Multiple Needs

Compounding the problem of evaluating single-pilot business aviation accidents is the fact there are several communities in this segment, each with its own issues, resources and regulatory requirements. Consider the following descriptions of these communities and you will see how difficult it is to come up with one-size-fits-all solutions.

Light Jets

At the top of the LBA food chain are the single-pilot jets. The pilots of these aircraft must have type ratings and take annual proficiency checks to serve as pilot-in-command. Often, insurance requirements also specify annual training and this is often done at “big box” brand-name training centers and in full-motion simulators. This is not universal, however, and a significant number of light jet owners receive their annual training in their aircraft from independent instructors. Their annual proficiency checks are often received from independent FAA-designated pilot proficiency examiners (PPE) rather than in a simulator from Part 142 training center evaluators (TCE).

Turboprops

There is a large community of turboprop aircraft, most of which do not require type ratings or annual proficiency checks. The only regulatory requirement is the flight review, which can be taken in any aircraft. However, insurance requirements generally require initial and annual recurrent training. While many operators avail themselves of simulator training at Part 142 training centers, a significant minority of owners again seek independent instructors to fulfill the training requirement, providing they can get their insurance companies to accept this option.

Piston Singles and Twins

At the bottom of the heap, so to speak, are all the piston drivers. This group itself comprises several communities. Heavy pressurized piston twin drivers usually face insurance requirements like the turboprops, yet even when there is a training center option many owners still choose to roll their own training program to meet the insurance requirements. The insurance requirements for initial and recurrent training become even looser for light piston twins and are almost non-existent in today’s insurance market for piston singles.

Type Club Resources

While I’m comfortable promoting NBAA’s actions on single-pilot safety (see above), I would be remiss if I didn’t emphasize that aircraft type clubs are very involved in safety issues such as single-pilot safety for their members. They often sponsor seminars, provide safety tools like flight risk assessment tools (FRATs), publish safety information in their journals, and hold annual meetings in which safety topics get top billing.

Just about any high-performance aircraft in service has an owners group supporting it. To pick one with which I am familiar and an associate member, I will highlight the Cirrus Owners and Pilots Association (COPA). The Cirrus SR series airplanes led the charge of modern glass-cockpit, technically advanced aircraft when they were introduced in the late 1990s. Unfortunately, their first few years were marred by a higher-than-average fatal accident rate. Part of this was because the Cirrus fleet flies more often in long-range transportation missions than typical GA aircraft. However, both COPA and the manufacturer eventually concluded that initial and recurrent transition training needed to be changed, especially regarding the use of the Cirrus Airplane Parachute System (CAPS).

The COPA website is especially detailed when it comes to safety information and analysis. This includes an analysis of the 119 fatal accidents that the fleet has suffered (as of August 15, 2016) and the 69 CAPS “saves” that might otherwise have become fatal accidents. The manufacturer also extensively analyzed SR accidents and made significant changes to initial and recurrent transition training. Collectively, the impact of these changes may be seen in reduced accident rates.

Tools and Tips

Regardless of whether you fly your high performance LBA for business or personal transportation, you don’t have to accept a high accident rate possibility as the cost of owning and operating such aircraft. You can take control of the situation by availing yourself of various resources so you can achieve a high level of both safety and utility.

Take risk management training and use these techniques on every flight to manage your risks. To get the most benefit, take a course that includes all elements of single-pilot resource management, including risk management, automation management, task and workload management, and maintaining situational awareness.

Join the owners’ association for your aircraft make and take advantage of the safety information and other resources they offer. Finally, look carefully for other safety resources on NBAA’s website. Some items are only available to members while other information is available to anyone.

Making LBA Safety More Visible

The single-pilot LBA community is now receiving more attention. The NBAA Safety Committee has formed a Single-Pilot Work Group (SPWG) to target LBA safety issues. I have been chairing this group for several months and, by the time you read this, we will have sponsored and conducted the annual Single-Pilot Safety Stand Down as one of the kick-off events at the association’s annual convention. The theme of the 2016 Stand Down was (drum roll)—single-pilot risk management.

One product developed so far is a Risk Management Guide for Single-Pilot Light Business Aircraft. This was intended to provide more useful risk management guidance to pilots than other documents. An example of what the NBAA guide contains is a more practical flight risk assessment tool (FRAT) than the numerical “score” FRATs commonly used today.

You can expect the NBAA to continue to make single-pilot safety a priority. The Risk Management Guide for Single-Pilot Light Business Aircraft should be available on the NBAA website by the time you read this. The SPWG likely will follow up with other tools and products in the next year.

Robert Wright is a former FAA executive and President of Wright Aviation Solutions LLC. He is also a 9600-hour ATP with four jet type ratings and holds a Flight Instructor Certificate. His opinions in this article do not necessarily represent those of clients or other organizations that he represents.