The potential for in-flight icing during an IFR flight—regardless of whether the airplane is approved for flight into known icing or not—means doing serious plotting and scheming prior to departure, and throughout the flight. As has been demonstrated for years, structural icing does bad things to airframes. Best to presume every cloud will contain ice, and plan accordingly.

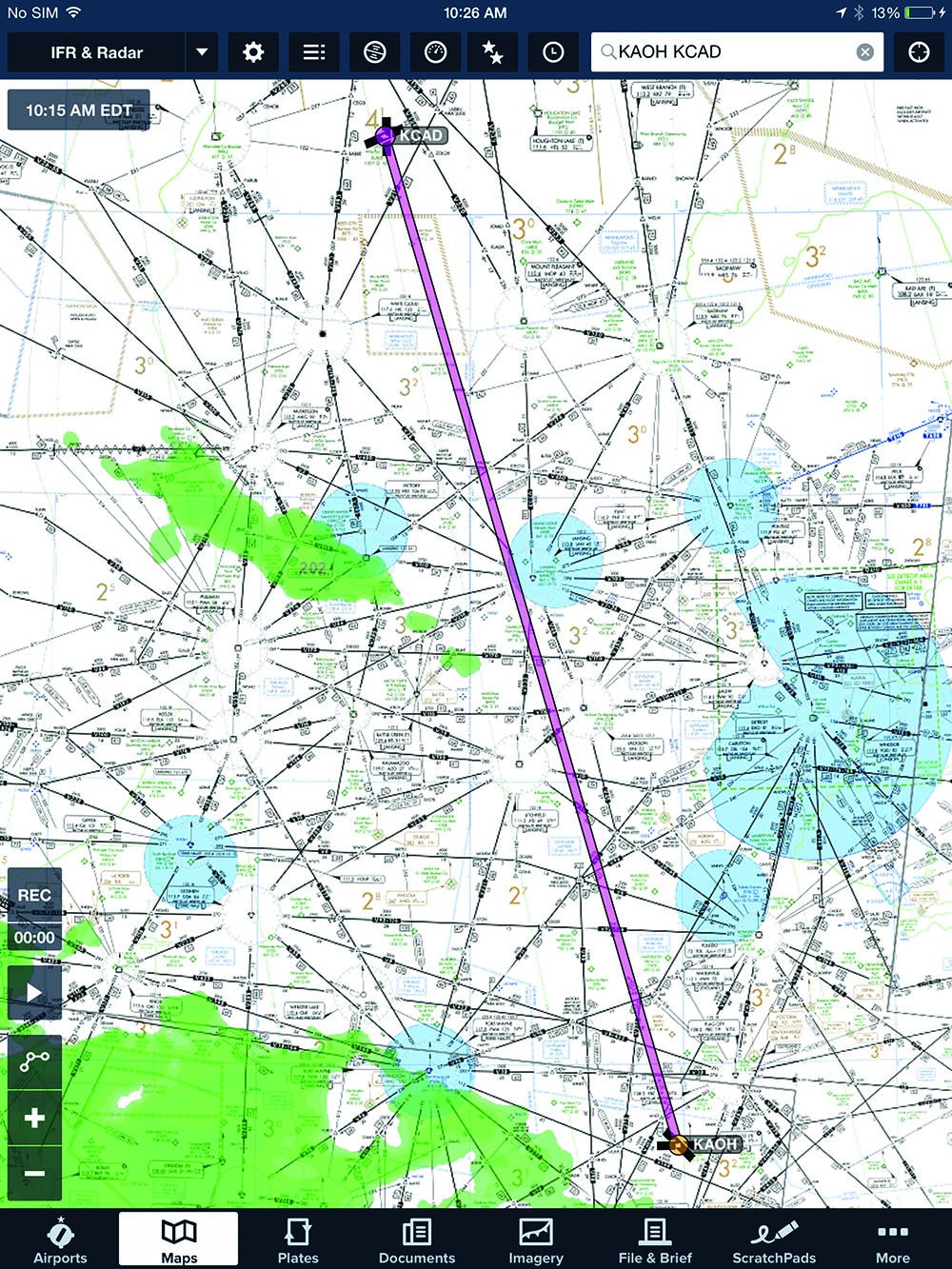

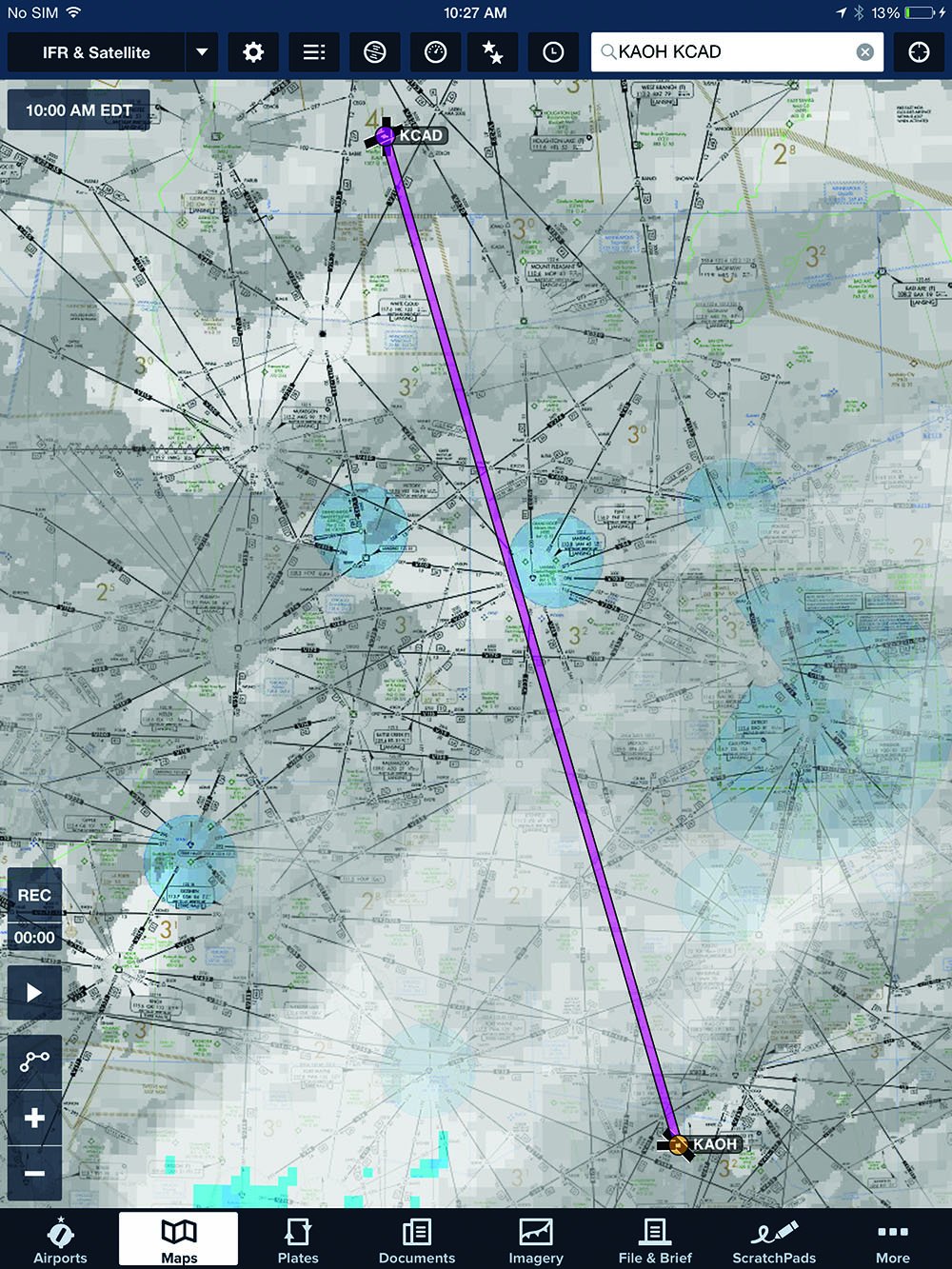

To illustrate our point, we’ll look at a hypothetical flight from the Lima (Ohio) Allen County Airport (KAOH) to the Wexford County Airport in Cadillac, Mich. (KCAD). (We’re going to KCAD because the FBO rents airplanes on skis and we purely love skiplane flying.) To get there, we’ll be flying a Cessna 177B Cardinal, a stable instrument platform with satisfactory climb and cruise performance, but lacking turbocharging or real ice protection.

The Big Picture

Looking at conditions along our intended route, we note surface winds are westerly at 15 knots, so lake effect conditions from Lake Michigan will enter the equation. We want to know where the cloud bases and tops are along our route, plus runway conditions at KCAD and possible divert airports. Weather conditions well to the east of our route are important, also, to determine the lake effect’s area and where a wide-open alternate might be. Oh, and winds and temperatures aloft would be handy. This is icing season, after all.

Today we learn cloud bases near Lake Michigan are 800 to 1500 feet, with layers up to the tops at 10,000. East of the Lake, bases are 1500 feet, tops at 6000. Manistee, on the Lake, west of Cadillac, is reporting 800 overcast and a mile in light snow. Cadillac is 1100 and two miles, which is about what Grand Rapids and Grayling are reporting. Scattered clouds in central Ohio become a layered overcast approaching the Michigan border. We’ll have maybe 10 knots on the nose, and the freezing level is forecast at 4000 feet msl.

We file direct to Cadillac because we are confident we can safely get on top, above 6000. But we’ll be prepared to go straight north until we can approach Cadillac from the east, to reduce our icing exposure. We file for 8000, an efficient altitude for the airplane, which should put us above the clouds and ice. The headwind isn’t too strong, and we’ll retain flexibility to climb or descend to stay out of ice-laden clouds.

Doing It

Once aloft and climbing northwest bound, we discover the scattered layer has become broken; soon we’re in fairly heavy snow. The OAT is -5 degrees C, so we aren’t going to be faced with wet snow plugging the engine air intake and requiring carb heat to pull air from inside the cowling.

Approaching 4500 feet, it’s apparent we’ll need to go through a deck above us to reach 8000. With the snow, visibility below deck is too low to go VFR. We’ve asked and been told that tops here are at 5500 feet. We’re climbing at full power (none of that 25-squared nonsense; the engine is rated for 180 continuous horsepower, which only occurs at 2700 rpm and sea level), because we want every bit of power we can get.

Zoom Climb

We level off, still at max power, just below the overcast and accelerate until the airplane is going as fast as it can, then pitch up gently to get through the layer quickly. We initially see more than 1000 fpm, which we hold as airspeed drops to VY plus 15 knots, but no slower (we don’t want ice forming well back on the underside of the wing).

If we can’t climb at VY+15, we’ll descend fast and return to Lima before we get so much ice that it’s a problem. The defroster is running full blast, the pitot heat has been on since before takeoff and we scoot through the 1000-foot-thick cloud deck with only a light dusting of rime ice. It will sublimate off in the next half hour.

Strictly legal? No. Safe? Reasonably. Will the FAA get excited? Probably not. Can we report light rime without being sanctioned? Yes. So we pass the word to ATC to let our fellow pilots know what we experienced.

We motor across central Michigan at 8000 feet, above clouds that swirl, change and break up. From time to time we see the ground and understand why visibility can so rapidly change. As they flow toward us from the Lake, the bands of cloud and snow are rapidly releasing the moisture they are carrying. By the time they flow this far downwind, only about of the land below us has cloud cover and snow at any given time. But because of the wind, what is and isn’t covered is constantly changing: The farmhouse we saw clearly three minutes ago is in heavy snow now.

In Range

Forty miles out of Cadillac, we ask Minneapolis Center about runway conditions and are told the runway is being plowed. The ceiling is holding at 900 feet and visibility is between one and two miles. The AWOS confirms the weather and we have solid alternates nearby, so we decide to press on.

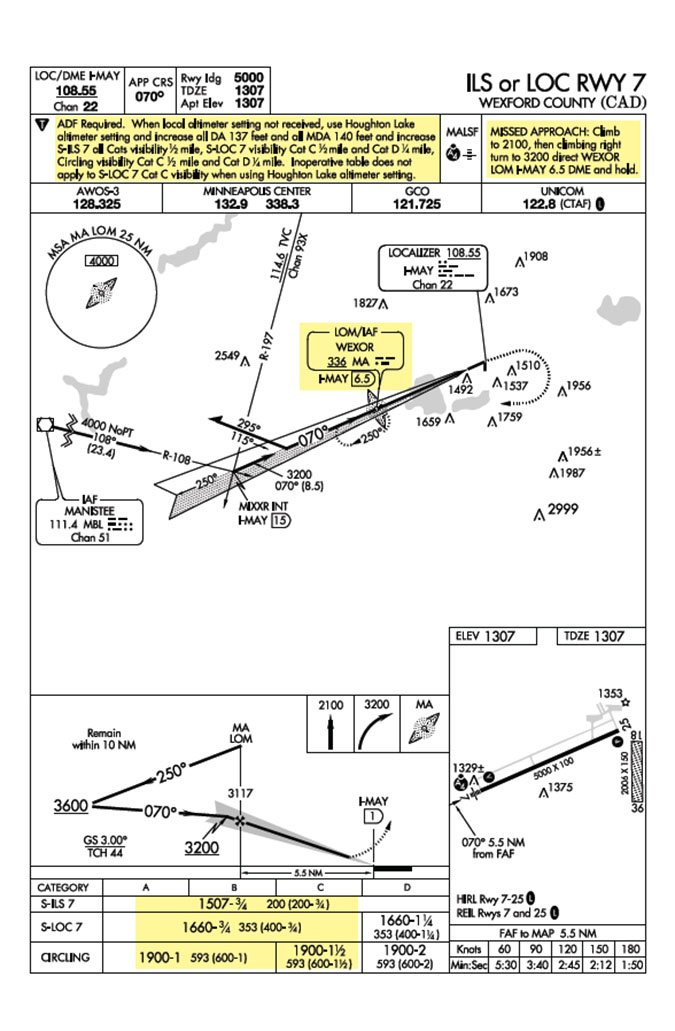

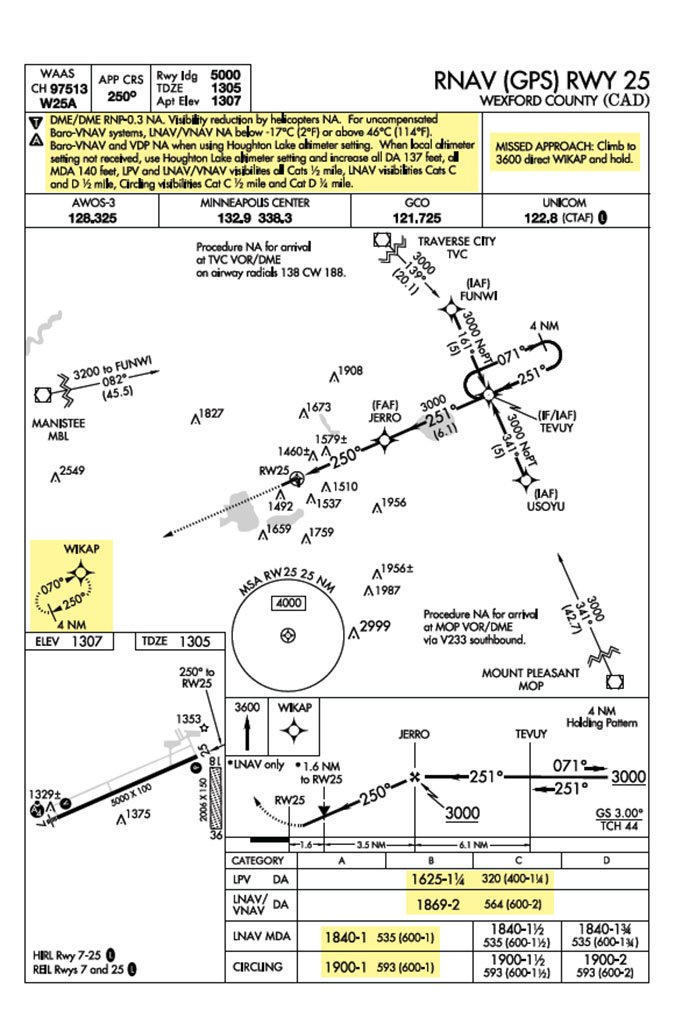

We’ll plan on the ILS Runway 7 approach instead of the into-the-wind RNAV (GPS) Runway 25 procedure. The ILS has a 10-knot tailwind, but the GPS requires 1 miles, which we may not have. (See the sidebar on the opposite page for more on selecting the best approach.) The trace of ice we picked up is gone, sublimated. On a westward vector for the ILS, we can see in the distance that the layer below rises to exceed our altitude.

A little discretion, please

Right about now, ATC clears us down to 4000 while we are still 20 miles from the final approach fix. That will mean flying level in what may be one of the layers below us, something we have no desire to do. We tell Minneapolis we’d prefer to remain at 8000 as long as we can and request a pilot’s discretion descent to 4000. Fortunately, controllers in this area of the world understand that concept very well and she agrees. We carry on, at 8000.

Just as we get the first turn toward the north aimed at intercepting the localizer, the clouds come up to meet us. We don’t want to linger in the tops—that’s where the absolute worst ice is—so we start down at 1000 fpm, keeping power and speed high to present the minimum frontal area to the ice.

At 5500 feet, we break out between layers, and slow our descent rate to 4000 feet, which puts us into the next layer as we intercept the localizer outside the FAF. The glideslope comes alive shortly and we follow it down, holding 120 KIAS, flaps up, for we know enough to never use flaps if we have any ice on the airplane when landing. We have another trace so far, which doesn’t overpower the defroster, so we can see ahead.

Arriving

We fly the ILS and call on the CTAF to announce our arrival. The snowplow driver answers and says he’s pulling off the runway. He adds that it’s snowing steadily and the south half of the runway is plowed, the north half has two inches of snow and there’s a snowridge down the center—a situation normal for smaller airports during lake-effect snow.

We break out, spot the runway and see the snowplow on a taxiway. Leave the power where it is, staying on the glideslope all the way to the touchdown zone. It would be very common to lose sight of the runway in the rapidly changing visibility, so maintaining our speed in the event we have to miss and go around at the last moment is a good choice. Even though, at 5000 feet, there’s plenty of runway, you might want to keep your Cardinal cooking until over the runway before reducing power.

If we did lose sight of the runway and begin a missed approach, we need to commit to it and not be seduced into changing our mind and make another play for the runway if it reappears. We’ve read too many accident reports of pilots who thought that seeing a runway 500 feet below them would allow them to make a tight circle to land. Discovering that 500 feet of vertical visibility doesn’t mean 500 feet of horizontal visibility, they crashed while trying to make a tight, low-altitude 360. Better to go around and rethink the whole idea.

We also need to keep in mind that the world around us is gray and white, and we likely will be experiencing “flat light” conditions, eliminating our depth perception. It’s the subject for an article all its own but we should never, ever duck under the glideslope when landing in overcast conditions with snow on the ground. On a non-precision approach, we need to cross-check the altimeter constantly until very short final: far too many pilots have come up short of a runway in flat-light conditions, then professed they were well above terra firma.

We’re going to use a lot of the 5000-foot runway because we know we are carrying some ice, so we won’t reduce power to idle until after we touch down, flaps up, somewhat fast. We’ve only got half the runway width, but there is little crosswind and we know how to use the flight controls to help us maintain directional control as we decelerate. Once on the ground and rolling on all three wheels, gently check braking, expecting it to be poor. All that remains is dissipating our energy and getting the airplane stopped before we reach the end.

Post-Flight

The guy in the plow will probably ask for a braking report. Unless we have slid off the end of the runway without noticeably slowing down, we will not give a “nil” report because that will effectively close the place down, something that can make us unpopular for those arriving behind us. Be careful not to exaggerate, but don’t think reporting it as “good” will do anyone any favors.

The final challenge will be taxiing to parking. If we’re in the middle of a major lake-effect event, even if the airport has excellent snow removal, it’s possible we’ll have to park where there is a clear area. That may be on the ramp and it may be on a taxiway. After we’ve just dealt with some very challenging weather, it’s always a little embarrassing to get stuck in the snow 50 feet short of the ramp.

Rick Durden is a practicing aviation attorney and type-rated ATP/CFI with more than 7000 hours.