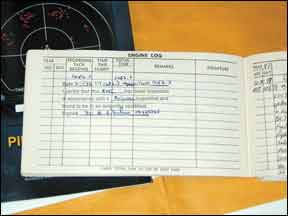

With a few exceptions, the typical personal aircraft is relatively reliable. Modern, solid-state avionics rarely break, we long ago figured out how to build and maintain mechanical flight instruments and, presuming the airframe is both flown and maintained regularly, dispatch reliability of personal aircraft often can be compared to the modern automobile. 288 But, stuff does break every now and then, usually right before were prepping to launch for a family vacation or an important business trip. Some failures automatically mean going via human mailing tube; others often can be resolved after a couple of hours in the shop. In between those two extremes are equipment failures which may reduce the aircrafts capabilities, but dont materially affect either its airworthiness, ability to fly or safety. How to know the difference and, more importantly, how to make the go/no-go decision based on whats broken and what still works? Whats The Mission? Lets presume you walk out to your airplane one morning and discover during the preflight inspection and run-up several items are inoperative. These items include the aircrafts position lights, a backup artificial horizon and an electronic engine monitor. You intend the flight to be conducted during daytime and under VFR. Can you go fly? The quick answer is yes, after attending to a couple of paperwork items and presuming the conditions under which the engine monitor was installed dont require it. First, the position lights arent required equipment for a flight in daytime conditions. Before takeoff, wed want to know why the position lights have failed and what, if any, impact the failure may have on other aircraft systems. For example, a loose wire at the wingtip and near a fuel tank could generate a spark. When this has happened in the wrong location and at the wrong time, excitement ensued. In fact, for a daytime flight, its normal to not even bother checking the position lights operation. Second, the backup artificial horizon isnt required equipment, either. Thats because a) its a gyro instrument and not required for VFR. Even if we were going IFR, the primary artificial horizon is working fine and thats all the FARs require. Regardless, neither instrument will be needed for this flight because we wont be operating under IFR. Normally, the engine monitor isnt a required piece of equipment, either, since the aircraft came from the factory with the appropriate and required engine instrumentation. While we consider an engine monitor an invaluable tool and would seriously reconsider launching on a lengthy cross-country without one that worked, its not an essential instrument. The exception is when the engine monitor is installed as primary instrumentation, replacing the original factory gauges. Several engine monitors are approved for such use, and often offer better information at higher resolution than the original equipment. The point is-even though all this stuff isnt working today-we can still take off. Why? Because the FARs say so. Crack open FAR 91.205 and review the list of required equipment for various types of operations. Of the three failed items on our hypothetical single-engine piston aircraft, none of them are listed, with the possible exception of the engine monitor, and its impact on our proposed flight depends on its status as primary or secondary instrumentation. If the former, its a no-go item. Other examples of no-go items might include an engine tachometer or a failed altimeter. Review FAR 91.205 as a starting point for a list of no-go items. Keep in mind: An item required for the proposed operation-night IFR in icing conditions, for example-may ground the airplane if its inoperative. Importantly, were talking about preflight actions here and failed equipment discovered before the aircraft takes off. If the failed equipment is discovered after takeoff, the rules change. Inflight discoveries of failed equipment should be handled in accordance with procedures found in the aircrafts AFM/POH, and consistent with safe operation and common sense. More Paperwork Even if the failed equipment isnt required for the proposed operation, youre not quite finished. FAR 91.213, Inoperative instruments and equipment, is the relevant regulation. 288 You will need to either remove the failed equipment and update the maintenance records accordingly-including a revised weight and balance report-or simply placard the device “inoperative” and deactivate it until it can be repaired. The placard may be as simple as a piece of masking tape placed on a failed instrument with the word “inoperative” written on it. This constitutes deferring maintenance on the inoperative equipment, as referenced in FAR 91.213(d). Deactivation usually means opening the offending equipments circuit breaker, thereby preventing it from operating and possibly doing other damage. In the case of an electric artificial horizon used as a back-up instrument, pulling the circuit breaker and attaching a zip tie to prevent the breaker being reset will accomplish deactivation. Placarding of such a device is depicted in the image on page 12. Applying the zip tie to the breaker, disabling the artificial horizon, technically requires a logbook entry by a person eligible to perform maintenance on the aircraft. Also referenced in FAR 91.213, the pilot or an appropriately rated mechanic, must determine “the inoperative instrument or equipment does not constitute a hazard to the aircraft.” In the case of the pilot, that determination need not be written down. In the case of a mechanic performing maintenance on the aircraft making such a determination, it probably should, since the aircrafts records always should reflect any work performed. A final option exists, also, and thats a so-called “special flight permit,” also known as a ferry permit. If the aircraft is rendered unairworthy by the equipment failure-however that term may be defined-and repairs cannot be accomplished at its current location, a ferry permit may be obtained by using FAA Form 8130-6. In addition to the equipment required in FAR 91.205, other considerations may render the aircraft unairworthy. An example would be an item required under an airworthiness directive (AD), or failure to perform a task or inspection required by an AD within the time allotted. Other Considerations Additionally, the act of disabling a piece of equipment and placarding it as inoperative only gets you so far: to the next required inspection, in fact. The relevant regulation is FAR 91.405, which requires “any inoperative instrument or item of equipment, permitted to be inoperative by Sec. 91.213(d)(2) of this part, repaired, replaced, removed, or inspected at the next required inspection.” In other words, if the operator determines the failed position lights discovered during the hypothetical preflight described above arent required to be operational before the next required inspection-whether its an annual, progressive or other inspection-they do need to be repaired and the repair noted in the aircrafts maintenance logs before that inspection is considered complete and the aircraft can be returned to service. In this example, of course, the only way for the position lights to be deferred until the next inspection is for the aircraft to be operated in daytime exclusively. If, between inspections, we decide to remove the failed equipment permanently, an appropriate logbook entry usually is required. This may involve an updated weight and balance report. If the failed equipment is removed, sent off for repair and reinstalled before the next flight, no such record is required, except for the fact of the repair itself. Deciding Whats Airworthy While its rare, at least in our experience, to discover for the first time an equipment failure during the preflight inspection, it does happen. Usually, finding the failure during the preflight results from an inadequate postflight inspection, or an unnoticed failure during the previous flight. Put another way, stuff happens. In fact, most equipment failures weve encountered over the years have been discovered on the first flight after maintenance: Something was disconnected or disassembled during the maintenance and wasnt correctly reinstalled. Thats one of the reasons the FAA allows only required crew to be aboard an aircraft for its first post-maintenance flight. Although this article cant cover every possible combination of aircraft, equipment, operation and situation, the considerations outlined should form a solid basis from which an operator may perform additional research. For the average personal airplane and its pilot, the FARs provide guidance and flexibility to enable making intelligent decisions on airworthiness. As always, operators need to consider the failed equipments impact on their proposed operation and whether the failure materially affects safety of flight. Most of the time, we can launch legally and safely with failed equipment, as long as we follow the rules.