My only real experience with of helicopters results from serving as self-loading freight on a handful of occasions. I know rotorcraft flying involves many similarities to fixed-wing operations: The basic FARs applying to rotorcraft pilots are the same ones governing fixed-wing drivers, for example. The charts often are the same; so are airport operations.

288

But the two aircraft types handle differently, and what might be a natural operation in one type—slowing down and hovering, for example—can only be done once when flying a fixed-wing airplane. In that regard, rotorcraft can be superior. But the additional expense of rotorcraft operations when compared to their fixed-wing counterparts means we generally would opt for the less-expensive and usually faster option of a fixed-wing airplane when planning and making a personal trip.

In addition to dealing with disparate aircraft types, overall performance characteristics can differ wildly between airplanes and helicopters. For example, someone accustomed to flying a King Air shouldn’t expect the same performance from a Robinson R-44. Likewise, someone experienced primarily with mid-level-altitude operation of turbine helicopters likely won’t be prepared for the anemia of a normally aspirated aircraft engine at density altitudes approaching 10,000 feet, especially if full power isn’t being used.

Alas, we’re also on a budget, so we opt to rent the less-expensive airplane for our trip. Because we fly for a living, we’re willing to risk overloading the less-powerful airplane. And we then put someone lacking a fixed-wing pilot certificate in its left seat.

Background

On May 29, 2012, at about 1258 Mountain time, a Cirrus SR20 airplane was substantially damaged following impact with remote mountainous terrain while maneuvering near Duck Creek Village, Utah. The private pilot and three passengers sustained fatal injuries. Visual conditions prevailed.

According to radar data, at about 1245, which was about 30 minutes after takeoff, the airplane was climbing through 6600 feet msl on a northeasterly heading. At 1250, it was climbing through 7100 feet msl, and at 1254:28 the airplane reached its highest recorded altitude for the flight, 7847 feet msl. Directly in front of the airplane about four miles away was rising terrain. The lowest ridge directly ahead was at 8470 feet, with terrain measuring more than 9000 feet in elevation on both sides.

Investigation

The airplane came to rest inverted on the west face of a mountain ridge, and about 100 feet below the top of the crest. All components necessary for flight were accounted for at the accident site.

The pilot-in-command (PIC) occupied the right front cockpit seat position and held airline transport pilot and flight instructor certificates for rotorcraft-helicopter. He also had private pilot privileges for airplane single-engine land, and an instrument-airplane rating. At the time of the accident, the pilot was employed as a commercial helicopter pilot by a local sightseeing and tour company was based in Las Vegas, Nev. His total flying time was 5668 hours, of which 160 hours were in airplanes.

The pilot flying, in the left front seat, held a commercial pilot certificate with rotorcraft-helicopter and instrument-helicopter ratings. He also held a flight instructor certificate, with rotorcraft-helicopter and instrument-helicopter ratings. He did not possess a pilot certificate for airplanes.

288

The departure-airport manager subsequently reported to the NTSB he observed the airplane occupants add fuel, during which it was remarked all four were helicopter pilots. Subsequently, they took off and performed a touch-and-go landing. The airport manager reported he heard someone say it looked like the airplane took an unusually long time to gain altitude after taking off.

The FBO renting the airplane to the PIC stated he had been observed overloading the airplane on earlier occasions. To load the airplane for the trip ending with the accident flight, the pilot taxied to another area on the airport, which was not visible to the FBO, to load his passengers and baggage. The pilot and his three passengers were on a fishing trip. Fishing rods, tackle and fishing licenses were located at the accident site.

When the airplane took off on the accident flight, it was estimated to be in excess of its maximum takeoff weight by about 225 pounds, or about seven percent overgross. It was further calculated the airplane was 177 pounds over its maximum gross weight—almost six percent—near the time of the accident.

At 1258, a weather reporting facility located about nine nautical miles east-northeast of the accident site reported wind from the southwest at six mph, a gust at eight mph, temperature of 80 degrees F, clear skies and an altimeter setting of 30.21 in. Hg.

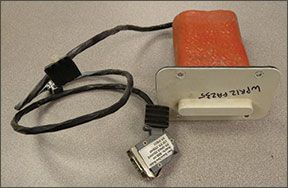

A Cirrus engineer used data recorded by the airplane’s onboard systems to reconstruct the accident flight. The data ended depicting pressure altitude of 7250 feet msl and an OAT of 15.5 degrees C. That computes to a density altitude of roughly 9000 feet. The airplane loaded to 3227 pounds should have been able to climb at 375 fpm at max-available power and the best rate of climb speed (VY) of 93 KIAS.

But the engine was turning at 2300 rpm, producing only 108 of its 200 rated horsepower. Climb performance was estimated at 22 fpm if flown at VY. The engineer added that the data appeared to indicate the airplane was being flown at 73 KIAS. The flaps-up stall speed for a 3050-pound SR20 is 69 KIAS. Correcting for 3227 pounds yields a stall speed of 71 KIAS.

Probable Cause

The NTSB determined the probable cause(s) of this accident to include: “The pilot’s failure to maintain sufficient airspeed and airplane control while maneuvering a heavily loaded airplane over high mountainous terrain in a high density altitude environment. Contributing to the accident was the pilot’s lack of experience operating fixed wing airplanes in such an environment.”

When confronted with terrain to clear, the helicopter pilots did what was natural: they slowed down, allowing the aircraft more time to climb. But they forgot airplanes don’t like it when things get too slow. If the airplane had been turbocharged—or just the more powerful SR22—they likely would have had the climb performance to clear the ridge.

Flying helicopter tours out of Las Vegas, as these pilots did, didn’t mean they could fly an overloaded airplane the same way: Hover mode wasn’t installed.