ICON Aircraft has been a media darling since the project was first announced. Founded in 2006, the company set out to create a different kind of light sport aircraft (LSA)—an amphibian, with folding wings for ground transportation and storage, and interior styling by BMW DesignWorks and Nissan Design America—that would appeal to a broad section of the current aviation community as well as to that huge potential market of non-pilots. The marketing emphasis was on recreation and fun, not transportation.

But after two fatal accidents in 2017, it’s a good time to look at how the ICON A5’s safety record might play out. The human factors, training program, risk management approach and safety culture of A5 pilots are all likely to be key elements in the product’s success. In the meantime, these factors offer insights into similar general aviation safety issues.

A Splash From the Beginning

The ICON Aircraft exhibit has been a top draw at the annual Oshkosh, Wis., EAA AirVenture fly-in for nearly a decade. Like most new general aviation designs, the A5’s gestation period was a long one. The aircraft went through several design changes as the company slowly spun up from scratch. ICON Aircraft sought and received an FAA exemption from the LSA 1430-pound gross weight limit (for amphibious aircraft) based on the handling and safety features that added weight to the design. Its maximum takeoff weight is 1510 pounds. And the airplane meets FAR 23 spin-resistant standards for certified aircraft.

ICON Aircraft has focused on operational and training issues as much as aircraft design in its intent to provide a safe experience for A5 owners. Yet those efforts proved controversial when the original purchase agreement was made public in 2016 and contained requirements for audio and video cockpit recorders, and a “responsible flyer” clause, plus ICON-approved pilot training and aircraft maintenance. Soon, the company released a revised contract dropping the camera/recorder requirement and the “responsible flyer” requirements but retaining those for training requirements and maintenance.

ICON surely took those steps because it knows why pilots are buying their airplane in the first place. It was designed to be a recreational vehicle with wings and thus will potentially expose the aircraft and its occupants to a variety of hazards and resulting risks for which neither the airplane nor the pilot may be prepared. However, it’s not possible to repeal the laws of physics. With only 100 horsepower and very limited payload, it’s easy to see how pilots could expose themselves to certain hazards and risks, especially if they do not practice effective risk management.

A Hypothetical

For example, let’s presume an A5 owner and his girlfriend have been invited to the boss’s cottage on a remote lake in the mountains about 150 miles from the plane’s home base. Oh, and could you bring your camping gear and two cases of beer? The weather for the weekend is marginal VFR. The lake is at an elevation of 5000 feet msl and it’s August, with temperatures in the 90s. There is no fuel of any kind at the lake. Our pilot doesn’t have an instrument rating, but it doesn’t matter because the A5 is not approved for IFR flight.

Besides the hazard of potential VFR into IMC that any non-instrument-rated pilot faces in these conditions, our intrepid pilot may be conditioned to accept other risks. In all his training and afterward, he has flown typically at 1000 feet agl or less.

He knows he has flown over gross before and the plane did fine on both water and runways at his home elevation of 1000 feet msl. He figures, what the heck, I can always put it down on any old lake if the weather gets worse. The potential hazards and associated risks keep piling up and are associated with LOC, CFIT, VFR into IMC and fuel exhaustion. Risk management is the only defense that could provide him with a mitigating strategy—if there is any.

Training Philosophy And Materials

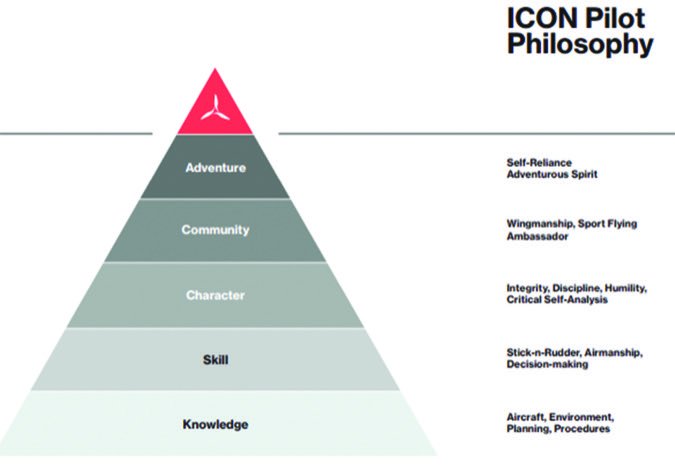

How does ICON propose to prepare the pilot for operating the A5 under all scenarios? This was the question on my mind as I arrived at company headquarters in Vacaville, Calif., in my Mooney. I met with Shane Sullivan, the Director of ICON Flight Operations, who was responsible for the training program. After the mandatory factory tour, we dived into it. I had previously provided Shane with some questions and he made every effort to answer them during his presentation: How does the training program deal with risk management proficiency? Will scenario-based training be employed? What about safety culture and how it might conflict with typical A5 operations? He provided the ICON Pilot Philosophy graphic shown below.

Despite decades of looking, I have not previously seen this kind of operational and training philosophy embraced by a general aviation aircraft manufacturer. I was pleased to see some elements of a safety culture described. However, I did not notice any reference to risk management, although decision-making at least was included. Furthermore, the company’s own web site displays videos and photos showing the A5 operating near hazards such as rocky beaches and cliffs.

The curriculum for ICON A5 pilots-in-training is tailored to the type of conversion training they require. There is a course for existing pilots transitioning to a seaplane rating, for example, and one designed for the non-pilot who is seeking a sport pilot certificate with land and/or sea ratings.

I was also introduced to the inventory of additional courses or modules available at ICON, including offerings such as mountain flying, high density altitude operations, open water operations and others. The training materials used at ICON were produced internally and were complete, comprehensive and of high quality. Besides the pilot operating handbook, it included a manual designed to cover the knowledge requirements associated with ICON operations, an operations manual covering maneuvers and procedures, and a course guide.

Following the first fatal accident, ICON published a low flying procedures document. Its Low Altitude Flying Guidelines covers subjects such as “soft deck” maneuvering, confined-area operations and box-canyon reversals. These guidelines are excellent, as far as they go, yet there is sparse information on hazard and risk analysis. The guidelines could have provided more information on common risks faced during low flying, such as obstacle and power-line avoidance. They could also have provided a primer on broader risk management techniques, including the three risk management components of identification, assessment and mitigation.

Safety Culture

Despite my concern regarding a lack of specific risk management training, I’d have to give ICON a solid “A” for aircraft safety design and at least a “B+” for the pilot training program. Yet despite this comprehensive approach to building safety into a product, the key determinant of the A5’s ultimate safety record may rest on whether or not A5 pilots embrace a safety culture in their operations and whether or not they take to heart the need to practice prudent risk management.

Of course, these concerns also apply to the wider general aviation community, but the A5 will have greater exposure to many of the risks associated with low flying, which will be amplified by the airplane’s range/payload/performance envelope. However, no one can predict at this point what the A5’s ultimate safety performance in service will look like, especially given the extent to which ICON has tried to produce a safe product and prepare pilots to fly it safely.

The Next Steps for ICON

So, what would I recommend that ICON Aircraft do to be even more proactive on safety? First, it might be appropriate for ICON’s CEO to make some public pronouncements on safe operation. This could be a difficult step for a company whose soul is firmly planted in the recreational community and whose founders’ backgrounds are mostly in the military fighter aircraft community. However, a strong, carefully crafted message might “lead by example” and resonate positively with the owner community.

Second, the company might want to add risk management to the training curriculum. It soon will be a requirement for sport pilot training and testing, and ICON could be in step with the rest of the general aviation community. By making the training scenario-based and tuned in to the A5’s mission profile, it could even be part of the “fun factor” surrounding this airplane.

Third, ICON could establish strong links and partnerships with the A5 owner community. If one has not already been established, an owner’s organization likely will form, and the company could make it a primary partner in developing a safety culture. This approach has worked well for other aircraft, such as Cirrus.

Meeting Design Goals

In researching this article, I wanted some first-hand experience with the A5. ICON responded by providing a flight in the A5 at its Tampa, Fla., training center, with a follow-up interview at the company’s headquarters in Vacaville, Calif. Our flight originated from ICON’s facility at the Peter O. Knight Airport (KTPF) and lasted about an hour.

With two of us aboard and partial fuel, we were near the maximum gross weight of 1510 pounds, leading me to conclude juggling payload will be a constant requirement during routine A5 operations. The aircraft’s performance at our near-sea-level location was more than adequate. I also found the A5 to have excellent handling and maneuverability. The aircraft had a very small turn radius and very large stall margins, if it can be stalled at all. A good part of our flight was spent at a nearby lake, performing water landings, takeoffs and maneuvering.

For a seaplane neophyte, I found the water takeoffs and landings to be easy, without any of the overly precise control movements needed by conventional seaplanes to get “on the step” for takeoff and for the landing flare. The angle-of-attack indicator is prominently placed for easy reference during all operations. The standard procedures for water and land operations emphasize situational awareness with respect to landing gear position. A landing on a runway with the gear up can be embarrassing and costly, but a landing on water with the gear down can be catastrophic.

The landing back at KTPF was uneventful and easy to execute. Even though my flight was only an hour long, I had to conclude that ICON had met its A5 design goals for maneuverability, ease of use and intuitive operation, and overall safety.

May 8, 2017, Lake Berryessa, Calif.

The facts of this accident are straightforward. A company employee was demonstrating the aircraft to a new employee and they flew to nearby Lake Berryessa where GPS data showed them flying right above the lake surface. They flew up an arm of the lake and into a canyon and apparently discovered it was a box canyon with no exit. The digital data indicated they were attempting to turn to exit the canyon when they impacted terrain. Both occupants died from the impact.

The NTSB’s probable cause finding: “The pilot’s failure to maintain clearance from terrain while maneuvering at a low altitude. Contributing to the accident was the pilot’s mistaken entry into a canyon surrounded by steep rising terrain while at a low altitude for reasons that could not be determined.”

This tragic accident unfortunately illustrates what could potentially be the leading safety issue for ICON. Low flying that results in either loss of control (LOC) or controlled flight into terrain (CFIT) have always been important “causes” of general aviation fatal accidents. An aircraft that flies near the ground routinely, such as the ICON A5 fleet is likely to do, may be even more vulnerable to these hazards.

Of course, as I have written before in this journal, the root cause of most general aviation fatal accidents is poor risk management. This includes LOC and CFIT accidents (see the May 2015 and November 2015 issues).

November 7, 2017, Clearwater, Fla.

The second fatal accident occurred after my visit to CONn company headquarters and while I was still writing this article. An A5 piloted by a retired baseball player impacted water in the Gulf of Mexico near Clearwater, Fla. Video taken by nearby boaters recorded the A5 maneuvering aggressively just above the water before it hit. As this issue was being finalized, the NTSB had not yet published a probable cause finding.

According to the NTSB’s preliminary report, “A witness to the accident stated, during an interview with [the NTSB], that he saw the airplane perform a climb to between 300 and 500 ft on a southerly heading and then turn and descend on an easterly heading about a 45 nose-down attitude. He then saw the airplane impact the water and nose over.”

The pilot was not inexperienced. He had about 700 hours total time, had been flying since 2013, and held a private pilot certificate with multiengine and instrument ratings. In an interview, the pilot expressed enthusiasm for flying low in an aircraft that handles “like a fighter jet.”

Some Lessons For All of Us

Even if you are not an ICON owner or delivery position holder, you can absorb the message inherent in how to safely operate low-powered recreational aircraft:

• Remember that fun and safe operation are not mutually exclusive.

• Practice risk management on all your flights and take risk management training.

• Organize your next flight review around a typical scenario in which you use your LSA or other recreational aircraft.

• Join your owner’s association and participate in its safety seminars, training and other activities.

Robert Wright is a former FAA executive and President of Wright Aviation Solutions LLC. He is also a 9800-hour ATP with four jet type ratings and holds a Flight Instructor certificate. His opinions in this article do not necessarily represent those of clients or other organizations that he represents.