Gettysburg, Penn., has a nice little municipal airport (W05). Its lone runway, oriented 06/24, is 3100 x 60 feet of well-paved asphalt and located just a couple of miles northwest of the historic town’s tourist attractions, and one of the most important battlegrounds in American history.

Wyoming’s Greater Green River Intergalactic Spaceport (48U) is a strong contender for best airport name in the open class. It certainly tops our list of unpaved, unattended strips with field elevations greater than 7000 feet.

The Clearview Airpark (2W2) near Westminster, Md., has fuel and a flight school—but its 1840 x 30 runway—with displaced thresholds at both ends—is challenging enough that the FBO offers celebratory coffee cups to fixed-wing pilots who manage to get down and stopped in time. (Helicopter pilots are apparently ineligible.)

Disparate as they seem, these airports have important features in common. One is that any of them would offer a safe place to land in an emergency. Another is that none would be a convenient place to park an aircraft needing service, or indeed a good spot from which to seek assistance. Gettysburg has no repair facility and no fuel sales to transients. Cab service or a ride-share might be scarce. The Greater Green River Intergalactic Spaceport, meanwhile, is a good four miles from town and has no facilities of any kind. There is also no line-of-sight between ends of its 5800-foot-long mountaintop runway, beyond which “land descends very steeply in both directions.” And even after refueling or repairs, some airplanes that could land at Clearview wouldn’t be able to take off again, at least not without offloading people, fuel and gear, and waiting for a day with negative density altitude and 30-knot winds down the runway.

Erik Brouwer

Getting safely back on the ground is always the first priority. But given alternatives, being able to get where you want to go, summon help if you need it, and get back in the air without involving your insurance company and a flatbed truck are also desirable outcomes. In situations less urgent than an engine failure or in-flight fire, the GPS’ “nearest airport” key may not punch up the divert airport that best suits your needs. Exactly what you do need depends on why you have to divert, and choosing the most suitable refuge may require information that’s not readily available in the cockpit.

Are We There Yet?

Perhaps the most common reason to divert is also one of the simplest: Someone on board needs a bathroom. (It could even be the pilot.) Unless the preflight briefing was very explicit, the subject’s apt to arise later rather than sooner, reducing the range of options. The resulting considerations are relatively straightforward: Find the nearest airport with adequate runways that has bathrooms…in a facility that can be expected to be open at that hour. Ideally, these will be found at a field whose runway configurations and surrounding terrain aren’t interacting with that day’s weather in ways that will fatigue your pucker muscles.

Of course, other amenities are also nice to have—maybe a flight-planning room with Wi-Fi where you can recheck the weather if it isn’t developing exactly as expected, or fuel priced in the range you were already willing to pay. In the eastern U.S., that may only require staying aloft for five extra minutes—but if you’ve really gotten away from it all, a safe place to land may be as much as you can reasonably expect. Bush pilots who carry extra rolls of paper products plus maybe a small shovel do so for a reason.

Something’s Not Right

In Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, Robert Pirsig wrote, “It’s just a feeling, but on a cycle you learn to trust them.” So, too, in an aircraft. If nothing looks odd on the gauges but you still feel uneasy, don’t assume it’s your imagination. Perhaps there’s a slight but unfamiliar vibration in the engine, or the color of the light slanting past those building cumulus reminds you of that afternoon just before all hell broke loose on your hike in the mountains outside Taos.

Unless the answer comes while en route, you’ll want to figure this out on the ground, but meanwhile you’ve got some time to decide where to set down. A maintenance shop is the first consideration if it could be an airplane issue; internet access and flight-planning services are very helpful in unsettled weather. In both cases, the most useful attribute may be proximity to a good motel if it proves impossible to sort things out on the spot.

Call an Ambulance!

If someone on board develops medical problems, the overriding priority is to get that person to care as quickly as possible. You’ll cover distance faster in the air than anyone could on the ground, but without the life-support capabilities of a properly equipped EMT team. Ideally, you’ll want to firewall it towards whatever field minimizes the time until you can hand the patient off to an ambulance or medevac helicopter—with possible exceptions including whether ground transport from that point would be much slower than continuing the flight (because, say, there’s a mountain range in between). Declare an emergency if you’re already talking to ATC; if not, find an approach frequency or tune to 121.5 MHz and broadcast a Mayday until somebody answers.

Meanwhile, point the nose in the right direction if you have even a rough idea what that is. The exception is if the stricken occupant is the pilot, which—unless a second pilot can take the controls—falls solidly into the “get down as fast as you can” category.

Better to risk expiring after landing than losing consciousness aloft, with the near-certainty of death and hazard to people and property on the ground that entails.

What’s That on the Runway?

A retired airline captain of our acquaintance recalls having had to divert nine times during his years flying international routes. Only two were for weather. Other causes included earthquakes, labor actions, a revolution that seized the airport while the flight was in the air…and several cases of disabled aircraft blocking the only suitable runway. That last isn’t terribly unusual, even in the U.S.

A problem as simple as a blown tire can present arriving pilots with the choice between circling while the airport operator rustles up a tug, or having coffee somewhere else while waiting. If this happens after the airport manager and FBO have locked up for the night, that’s an easy call, provided your fuel supply gives you that luxury. Arriving with a scant 30-minute reserve only to find the airport closed is not a comfortable feeling, which is one reason we advocate maintaining at least double the fuel reserves required by regulation: an hour for a daytime VFR flight in an airplane, 90 minutes IFR or at night, and 40 minutes flying VFR in a helicopter.

Other complications that may arise include inoperative pilot-controlled lighting or airport beacons, wildlife that won’t move off the runway—and even the overnight destruction of the airport in violation of federal law (are you reading, Richard Daley?). And, of course, there’s also weather: Ground fog can blanket an airport on an otherwise clear evening (or morning).

The point is that a flawlessly conducted flight doesn’t guarantee being able to land at your intended destination. When that happens, it’s good to have a more specific plan than circling a thousand feet above pattern altitude while frantically scanning the sectional.

Too Many Questions

Trying to simultaneously anticipate all those possibilities would take us back to the exhaustive planning that preceded our first solo cross-countries. Old-school instructors have students write down the frequencies, runway lengths and alignments, and prevailing weather at every airport within 50 miles of their route.

That level of preparedness tends to relax after the checkride and a few more cross-country flights have gone into the logbook, but it’s still a good idea to reserve a bit of flight-planning time for sketching out what Plan B might look like during various phases of the flight. It’s not necessary to replicate the voluminous notes of your student-pilot days to have a general sense of where you’d turn if you needed gas, restrooms or troubleshooting. Figuring that out in advance—with no time pressure and abundant sources of information—simplifies decision-making and reduces workload if a diversion’s actually needed.

The resources available to sort this out in the cockpit are less predictable. Yes, ATC can help—if you’re already talking to them or can find the right frequency. The GPS databases available in installed avionics often include detailed airport information that should be as current as the database itself. Mobile phones and tablets running aviation apps can be tremendously helpful…if you can get a signal, the device doesn’t overheat and its batteries don’t run down.

For sheer reliability, though, we’re still fans of paper (see “Cheap Insurance,” below). And none of these sources may list some landing zones of last resort, including closed airports, military fields, turf farms and even highways. Good alternate planning begins with choosing a route offering a reasonable range of options. Do you really want to follow that Victor airway directly across the mountains, or stay within sight of the Interstate, just in case? Would a less direct route offer more options for rest stops?

Finally, the decision that works when you’re flying solo might not be optimal when you’re carrying passengers who have little prior experience in light aircraft.

Yeah, But I Always Go IFR

Planning for a legal (or “for-real”) IFR alternate merits an article of its own, but it’s worth mentioning a few guidelines, some of which directly transfer into the VFR world.

First off, always have one in mind even if the forecast makes filing it optional. It’s a decision you want to make in advance (while reserving the right to change your mind if needed). You’ll want to include that alternate in your preflight briefing, especially for Notams—climbing out and requesting vectors after the initial miss is not the time to find out the localizer at your solid-gold bolt-hole is out of service.

Assuming an instrument approach may be necessary, the first priority is finding some combination of higher weather and lower minimums that provides a near-certainty of being able to get in. In January 2013, the pilot of a Piper Arrow attempted four non-precision approaches in a widespread area of low IMC covering the Mid-Atlantic and finally ran out of gas while being vectored for an emergency landing at Dover Air Force Base in Delaware. Needless to say, that is not what you want.

A secondary consideration is that if you’re diverting, other people will be, too. Choosing a smaller field that won’t attract displaced airliners will help minimize delays and associated stress.

Cheap Insurance

At a safety seminar some years ago, the instructor asked the audience how many kept the current edition of what was then called the Airport/Facilities Directory in their flight bags. Three people raised their hands—out of about 120. That’s a shame, because what’s now known as the Chart Supplement isn’t just one of the most complete and authoritative references available—it’s also among the cheapest.

FAA

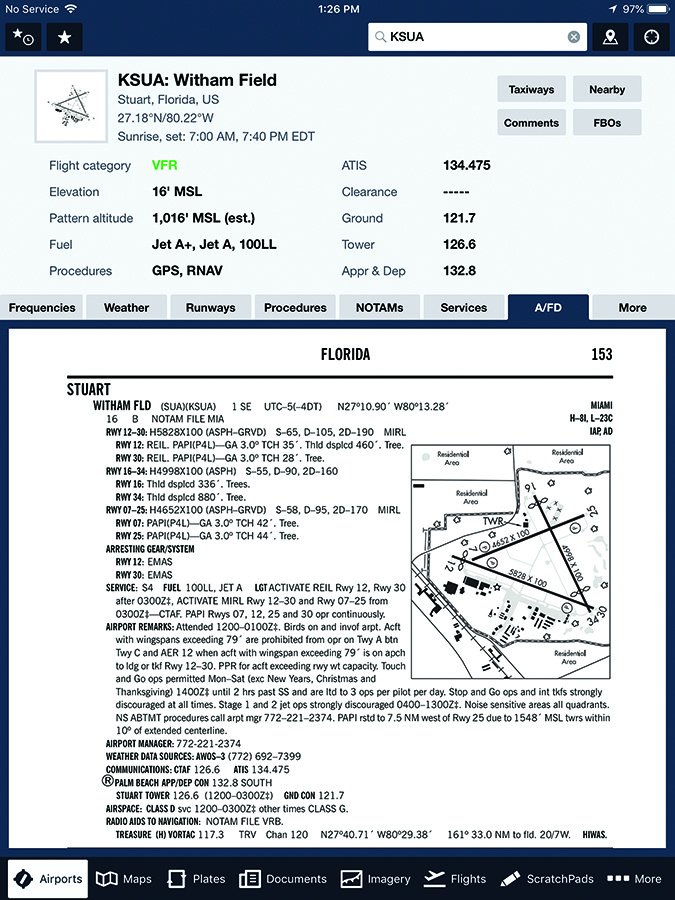

True, it won’t tell you how far you’ll have to go to find good barbecue, or even whether there’s a courtesy car. It will, however, give you the hours at which someone should be there, the kinds of fuel available and whether there’s 24-hour self-service, phone numbers for the airport manager or to request after-hours services (if available), the dimensions and pattern orientations of all runways… plus latitude and longitude, bearings and distances to the nearest navaids, frequencies for approach control, weather, and the CTAF or tower and descriptions of possible conflicts such as banner tows or skydiving. It even details what repair services are available, though you might have to look up the codes. (“S4” means “major airframe and powerplant.”) That’s a lot of information for seven bucks—and the batteries never run down.

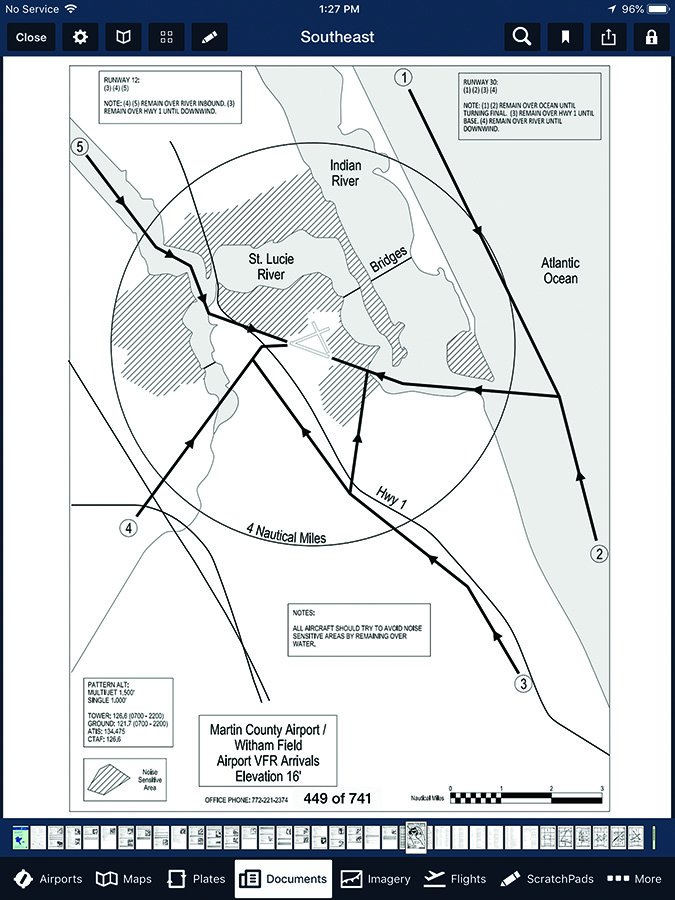

Accepting the premise that paper is pass, those of us using an electronic flight bag usually can find the same information, although it might take a little digging. ForeFlight offers a dedicated “A/FD” button in its airport view, which pulls up the facility’s principal Chart Supplement entry, including an airport diagram. But that may not be everything you need or want to know. For example, pulling up the A/ FD entry for Stuart, Florida’s Witham Field (left-KSUA), won’t tell you there are local noise-related VFR arrival and departure procedures. In a divert situation, you may not care about making noise, but the local pilots do.

Playing ‘What If?’

Being the person in charge of a flight’s safe outcome is an awesome responsibility. It’s one that takes on even more definition when “something happens” and you need to be on the ground with the right mix of facilities, services, alternate transportation and, perhaps, a place to eat and sleep.

FUEL CONSIDERATIONS

Deciding where and when to land when a problem arises is a lot simpler when you have plenty of fuel to get to your chosen divert airport. Yes, if you’ve chosen well, you can get more once you land. But removing fuel considerations from the decision helps you make it on its merits.

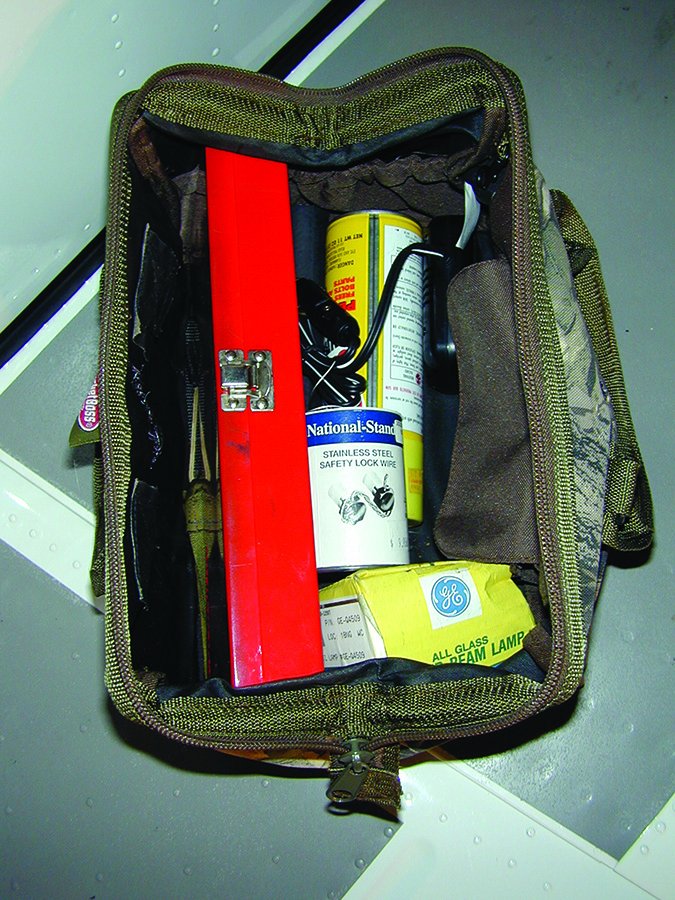

TOOLS AND PARTS

If you’re handy and familiar with your aircraft’s mechanical needs, carrying an assortment of the tools and parts for common problems can be prescient. But it’s unlikely you can carry everything necessary to, say, change a flat tire. A spark plug or a landing light likely won’t be a problem, however.

DOCUMENTATION

Even if you’re not going to do the work yourself, the technician may not have reference materials for your aircraft. It can be awkward to carry a full set of the maintenance and parts manuals for it, but electronic versions are widely available and can easily fit onto your EFB.

David Jack Kenny still owns the 180-hp Piper Arrow he flew on his commercial checkride in 2004. He also holds commercial privileges for helicopters and was previously the statistician for AOPA’s Air Safety Institute. There’s no truth to the rumor he deviates early and often.