One of this magazines missions is to help reduce general aviations accident rates. Ideally, there would be no fatalities. We want to see an end to poverty and war, too, but were not holding our breath on either. In the world of aircraft, a mechanical world, things are still going to break and pilots are going to have to respond quickly, thoughtfully, and appropriately in order to make aircraft accident fatalities go away. Sometimes they may have to augment that skill with luck, too.

How much luck? Think about this scenario: Theres a road in a dense forest with no electric or telephone wires strung across it at the point where a pilot manages to put his small craft down on the pavement. Oh, and there are no cars touring that particular stretch, despite the fact its peak leaf-viewing season. There was knowledge in the way the relatively low-flying pilot responded immediately to the loss of power by reducing his pitch attitude to achieve the airplanes best glide airspeed and avoid an accidental stall/spin.

Been There, Done That

There was skill in the way the pilot maneuvered his aircraft without hesitation toward the one possible landing site, a site he most likely had eyed earlier in the flight (just in case). But the fact that it was an empty stretch of road tracing a narrow, obstacle-free path through dense forest? That was luck.

Another pilot I know had a complete engine failure in a multi-engine airplane at 7000 feet, while in cruise climb. He was startled, but his training kicked in within a second, he told me. And that comforted him. How? His training reminded him of his airplanes single-engine capabilities, and he realized in a single moment that, at that days configuration and load, he was entirely capable of both maintaining altitude and flying on one engine right back to his home base, where maintenance was readily available. So, once hed run his checklists and determined that the engine would not restart; once hed feathered and secured the bad engines prop; once hed adjusted his fuel for proper balance and set the power on the good engine so it would not overheat and be damaged; once he declared an emergency with ATC (he was IFR), he took his craft home.

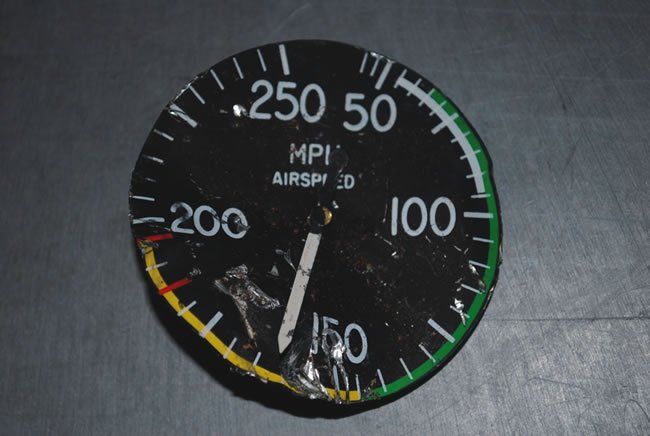

Upon arrival he set up a nice, long, stable final approach at his normal approach and landing airspeeds. (Counterintuitive as it may be, this is a weak spot for many-they get close to the runway but forget that best glide is not final approach speed, or, alternatively, they add knots as some kind of compensation for the loss of engine power. It doesnt work and results in an inordinate number of runway overruns during engine-out landings.)

Yet another pilot, this time flying a single, lost his engine right over the same stretch of real estate last year at about the same altitude, and, again, by following the procedures hed been trained to use, made it safely onto a runway that was slightly behind him and within his 10-nm glide radius. This pilot used ATC as a part of his emergency team, insisting that Jax Center stay with him to the ground. That meant the controller liaised with the Ocala ATCT to clear the airspace and runway while the pilot stayed focused on flying. Delegating that job to ATC was one in a series of good decisions.

When asked what he would do differently next time, this pilot was quick to admit that he was happy to have a long runway in front of him, because hed caught himself adding those knots for family and friends to his final glide, and holding the flaps in reserve until he touched down halfway down the runway without them. The good news was he had enough inertia to clear the runway, making the tower controllers smile. If he had it to do over, though, he told me hed definitely stick to the aircrafts book airspeeds. Looking at the end of that runway coming up while waiting for the flare to settle so he could add brakes was rather unnerving to him, to say the least.

Both pilots had their share of luck, too: Their engines quit at altitude, buying them precious time to establish a glide to an airport and then troubleshoot the issue. When your engine quits close to the ground things happen much more quickly. There is no time for disbelief, or even troubleshooting. Avoiding a stall requires a brisk push of the yoke to establish best glide (well assume you were climbing). Finding a place to put the bird is a nearly instantaneous decision, and returning to the runway behind you is typically not an option, unless you are in a craft with a glider-like lift-to-drag ratio.

Where I operate, there are buildings and a golf course at one end of the runway, and a forested, swampy area with a road and powerlines at the other. I have scouted potential emergency landing sites at both ends, and they are different for each aircraft I fly. Scouting those sites saves me precious seconds in a real emergency. I know from experience that no matter how much perceived time slows down when the adrenaline hits your bloodstream, real time keeps on ticking, and the ground gets close faster than youd think.

Night Engine Failure

Just ask Emanuel Kanal, who had a partial engine failure flying at night. Kanal narrates the experience, framed by the actual ATC tapes, for an AOPA Air Safety Institute Real Pilot Stories presentation. He watched as cockpit engine indications warned him of an impending problem, and then, before he could even diagnose what he was seeing…boom.

Though he didnt know it at the time, his single engine had thrown a connecting rod. It felt as if the engine was going to come apart, he recalled, pulling the power to stop the shaking so he could read the G1000s instrumentation and, with help from ATC, get the airplane pointed at an airport. Except, he couldnt glide there.

Kanal quickly figured out he had to adjust what power he had left to get his Columbia 400 into position for an on-airport landing-off-airport landings at night almost guarantee a bad outcome. Quelling the terror from the horrific vibration, Kanal kept his cool and found a power setting that got him onto a usable glideslope to a safe landing on a nearby runway. Altitude was his ace-in-the-hole. The 10-minute Flash presentation is worth your time, and is one of several enlightening confessionals available. Go to tinyurl.com/AvSafe-AOPAASI for more details and to view the presentation.

In the Moment

All of the pilots I spoke with and listened to while researching this article credited their training plus a willingness to suspend disbelief and stay in the moment to ensure successful outcomes to their in-flight emergencies. Every one of them told me something I already knew from my own experience: There was plenty of time for contemplation once the emergency checklist was complete and the aircraft was set up on a final approach to landing.

Contemplation, you ask? Yes. Remember how I said adrenaline focused inward makes perceived time slow down? That moment you are looking down your final glide path at your landing zone is your gut-check moment. Its when you need to summon every last bit of discipline you have, stay with your training and set up the most normal, perfect, power-off landing youve ever performed. Thats when you tell yourself, Just do it right. Im convinced thats when the training pays off.

Breaking the Chain

Heres the thing: You dont need to wait for an emergency landing out of an engine-out scenario to have a gut-check moment. Ive taken to having one every time theres an anomaly I need to puzzle out in my cockpit in flight. Do I smell melting plastic? Could it be an electrical short? Is a fire imminent? Will I need to revert to backup power sources, backup instrumentation or, worse, shut down the electrical system?

For example, a rough-running engine could present itself as many issues. Is the fuel flow too high, or too low for the power settings and condition? Is an EGT or CHT indication trying to tell me Ive got a cylinder problem, a clogged fuel injector or an exhaust leak? Is it an ignition issue? Or perhaps the weather ahead suddenly takes a turn in a direction or intensity I had not anticipated. Am I ready with a safe alternative and the fuel to get there?

Ive got memorized procedures and checklist-dictated procedures for each of these tricky gut-check moments in the air and I make a point of rehearsing my planned actions with some regularity, so there will be no delay in my response to them. I know those moments may not have the intensity of staring down the glidepath of an off-airport emergency landing, but I maintain that by running a prescribed rubric-often in the form of a concise checklist for any anomaly in my cockpit-I can maximize the possibility of normalizing, or at least minimizing the problem and continuing the flight to a successful outcome. And if we all did that? We just might get closer to the goal of zero general aviation accidents.

Do I believe in an aviation world where there are no accidents in a year? Maybe not. But I do believe we can cut those fatalities down, possibly even to zero. Its a stretch, certainly, and it will require some luck. But it is one worth training for.

Amy Laboda is a freelance writer, ATP, CFII-MEI and a National Lead FAAst Team representative. She and her husband own and fly a Kitfox and an RV-10.