According to the FAA’s advisory circular on the subject, controlled flight into terrain (CFIT) occurs when “an airworthy aircraft is flown, under the control of a qualified pilot, into terrain (water or obstacles) with inadequate awareness on the part of the pilot of the impending collision.” That same advisory circular (AC 61-134, General Aviation Controlled Flight Into Terrain Awareness) tells us “about 25.0 percent of all accidents occur during the takeoff and initial climb segment of flight. Approximately 7.0 percent of the accidents occur during the climb portion. Only about 4.5 percent occur during cruise. About 19.5 percent occurs during descent and initial approach. But 41.4 percent of the accidents occur during final approach and landing.” In other words, when we’re flying close to the ground, we’re at greater risk of running into it.

That makes perfect sense to us, and we generally avoid getting too close to the ground or other objects, except when taking off or landing. The problem resulting in many CFIT accidents, however, is that the pilots didn’t know they were about to run into something. Poor visibility, night operations and mountainous terrain all figure prominently in CFIT accidents. Perhaps the most typical CFIT accidents, however, occur when pilots inadvertently encounter instrument conditions and don’t turn around.

At the same time, pilots accustomed to flying in the eastern half of the U.S. are at much greater risk of CFIT when they stray from their familiar—and relatively low—routes. In what we think is a classic CFIT accident, that’s exactly what happened to two brothers flying literally across the country.

Background

On May 6, 2014, at 1159 Mountain time, a Mooney M20C Mark 21 collided with mountainous terrain near Cody, Wyo. The private pilot/owner and private pilot-rated passenger sustained fatal injuries. The airplane sustained substantial damage to the forward fuselage and both wings. Instrument conditions prevailed at the accident site. Neither pilot held an instrument rating.

Both occupants were octogenarian brothers and had departed Fayetteville, N.C., on April 28. Their plan was to tour the country by air, visiting friends and relatives along the way. Seattle, Wash., was their ultimate destination. The cross-country flight departed the Yellowstone Regional Airport (KCOD) in Cody at about 1140, with a presumed destination of Twin Falls, Idaho.

Family members became concerned when they had not heard from the occupants by May 8. On May 10, Lockheed Martin Flight Services issued an alert notice and radar data from the U.S. Air Force Rescue Coordination Center was used to help local officials find the airplane. The wreckage was located at an elevation of about 9970 feet msl on the eastern side of a mountain and about 430 feet below its summit.

Investigation

Both occupants held current pilot certificates and the airplane was equipped with dual controls, so a definitive conclusion regarding who was acting as pilot-in-command at the time of the accident could not be made.

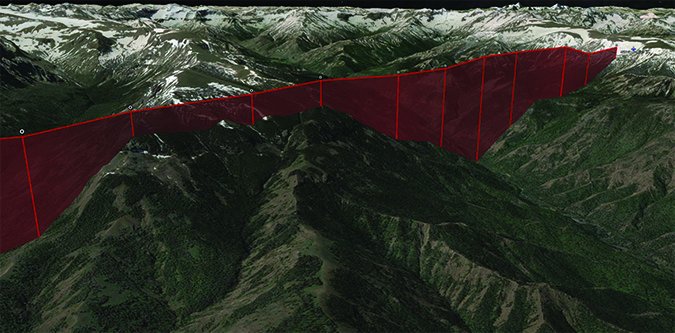

Radar data from a sensor 60 miles east of the departure airport revealed a VFR transponder target flying on a track of 248 degrees toward rising terrain. While flying at 9900 feet msl, it passed below a 10,219-foot peak about a mile to the south. The track progressed for another two minutes and climbed 200 feet while clearing an adjoining ridgeline by 300 feet, then began a climb to 10,500 feet as the terrain below fell away to 6900 feet. The last recorded target occurred 24 seconds later, at an altitude of 10,200 feet msl.

Lockheed Martin Flight Services reported it had no record of the airplane’s registration number being used to request a weather briefing during the three-day period leading up to the accident.

At 1135, the automated observation at KCOD (elevation 5102 feet msl) included wind from 360 degrees at 12 knots, visibility unrestricted, a few clouds at 1300 feet agl, broken clouds at 1900 feet and overcast clouds at 3100 feet, or about 8200 feet msl. The KCOD forecast predicted marginal VFR conditions, with rain showers, lowering ceilings and visibilities down to two miles. According to the NTSB, there was “a full set” of Airmets covering the region, reporting mountain obscuration, turbulence and icing.

The initial route of flight took the airplane into a mountain range including peaks in excess of 12,000 feet msl. Beyond the accident site were lower open areas.

The main wreckage came to rest facing uphill on a 30-degree slope. The main cabin was upright on a heading of about 290 degrees magnetic. Snow depths in the area ranged from three to five feet. Examination of the airframe and engine did not reveal any anomalies precluding normal operation.

According to the Great Falls Sectional Aeronautical Chart that was current at the time of the accident, the depicted maximum elevation figure in the area of the accident site was 12,500 feet msl; the accident site was located at 9970 feet. The route of flight spanned the Great Falls and Salt Lake City Sectional Charts. Although a full complement of charts was located in the rear pocket of the forward left seat, the only chart located in the forward cabin area was for Seattle.

Probable Cause

The NTSB determined the probable cause(s) of this accident to include: “The non-instrument rated pilots’ decision to continue flight into known instrument meteorological conditions over mountainous terrain, which resulted in controlled flight into terrain.”

According to the NTSB, the airplane entered clouds almost immediately; its flight track began to waver slightly about seven minutes after takeoff, likely because it was being hand-flown in IMC: “The flight track remained generally on course toward the destination airport as the flight progressed, and there was no indication of an attempt to return to the departure airport.” The airplane flew through the mountainous terrain in IMC consistently about 2500 feet below the maximum elevation figure of 12,500 feet msl shown on the pertinent sectional chart.

The NTSB said its investigation “was unable to determine why the pilots elected to fly at an altitude below the maximum elevation for the area.”

Avoiding CFIT

The NTSB’s Google Maps-based recreation of the accident airplane’s flight path is at right. According to the FAA advisory circular AC 61-134, General Aviation Controlled Flight Into Terrain Awareness, pilots should consider the following to avoid CFIT:

– Non-instrument rated VFR pilots should not attempt to fly in IMC.

– Fly a minimum of 1000 feet above the highest terrain in your immediate operating area in non-mountainous areas. Fly a minimum of 2000 feet above it in mountainous areas.

– Verify proper altitude, especially at night or over water, with a correctly set altimeter.

– Maintain situational awareness both vertically and horizontally.

– Comply with appropriate regulations for your specific operation.

– Don’t operate below minimum safe altitudes if uncertain of position or ATC clearance.

Aircraft Profile: MOONEY M20C MARK 21

Engine: Lycoming O-360-A1A

Empty weight: 1525 lbs.

Max gross to weight: 2575 lbs.

Typical cruise speed: 158 KTAS

Standard fuel capacity: 52 gal.

Service Ceiling: 17,200 ft.

Range: 748 nm

Vso: 50 KIAS