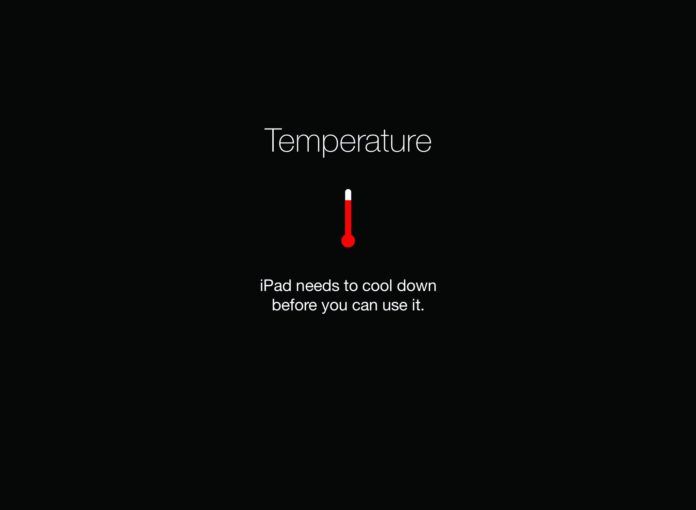

There I was, all strapped in with the engine running, sitting on the ramp at Class B International. I’d flown in a few minutes earlier for a stop, drop and hop, and my passenger was well on his way to the airline terminal for his human mailing tube home. I was looking forward to getting back to my own home after a couple of days on the road. With the big, front-mounted fan cooling me off, I hit the home button on my yoke-mounted iPad mini 2 to pull up its ForeFlight installation and look up the ATIS. I was greeted by a BSD (black screen of death): My iPad had overheated, sitting in its mount on a warm September afternoon. Oh joy.

Over the last 10 years, electronic flight bag (EFB) software running on a portable device of some sort has revolutionized the way we fly. One device, often capable of slipping into a pants pocket, can contain and display every VFR and IFR chart, terminal procedure and speck of aeronautical information that used to require pounds of paper. Properly equipped, it can display slightly delayed Nexrad weather radar, nearby traffic and its own position on an electronic version of all those charts we used to carry. It can even show me where I am on an airport taxiway and the direction to turn toward the runway. If it didn’t already exist, someone would have to invent it, if for no other reason than to save some trees. But the EFB as it’s implemented in many cockpits—especially when based on a consumer-grade product with a relatively narrow operating temperature range—isn’t perfect.

Belts And Suspenders

Sitting on that ramp with the engine running, I twisted knobs on my panel’s Garmin GNS 530 to identify and load the correct ATIS frequency, then the one for clearance delivery, and jotted down the ground and tower frequencies I expected. With little further ado, I got my VFR clearance out of the Bravo, taxied, took off and flew home. By the time I was tucking the plane into its hangar—and probably well before, actually—the iPad had cooled down enough to power up without an error message. The episode wasn’t the end of the world, but it did force me to consider some things.

Item One on that list, of course, is to not leave the iPad in its mount where it can soak up the sun’s heat energy. That’s a simple solution, but it’s not always effective in the summer. Dismounting the iPad and stashing it somewhere in the cabin isn’t my first choice, and often it will get just as hot. Placing it on the floor is a proven recipe for damage. Carrying it into the FBO risks forgetting or misplacing it.

Item Two is to carry a backup. As it happens, I have a second, identical iPad mini 2 I usually carry when flying, but left it home on this milk run. The 530’s data was up to date and—as it did before the advent of EFBs—was ready to pull up the frequencies and aeronautical information I needed to get out of Dodge. It served as the backup I needed. But while the 530 will navigate me through any approach and to any navigational fix, it won’t display charts, fuel prices or any of the other goodies I’ve come to expect on a portable device. Yes, I can write a check to solve that, but buying even 20 iPads would be much cheaper.

Item Three is a fervent wish for a more robust hardware solution, one that doesn’t shut itself down in plausible situations. Yes, there are aviation-specific products offering similar functionality, for a premium, and I will look closely at some of those options going forward. But they, too, have their limitations and require learning a different application. Whatever choice I make may not play well with my ADS-B In receiver, however, an L3 Lynx 9000.

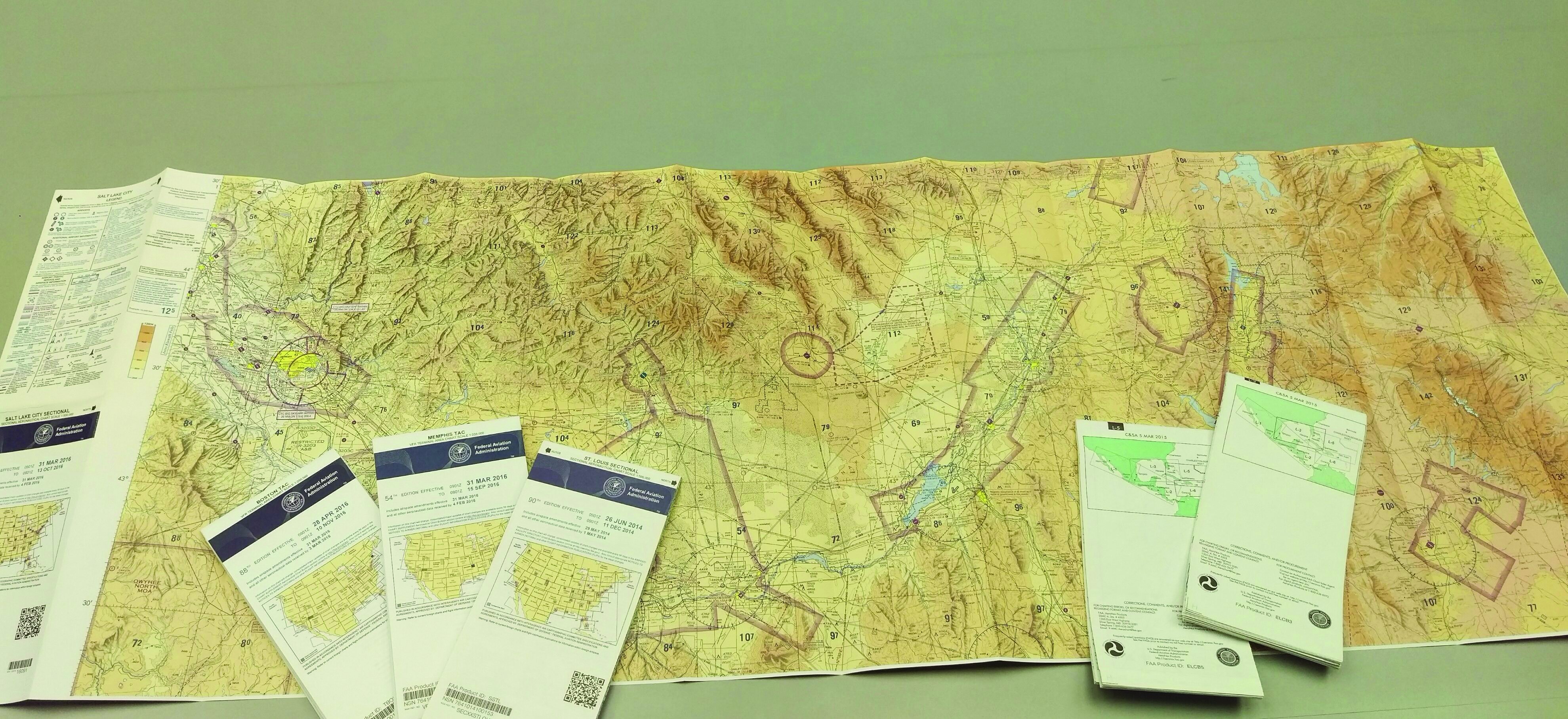

Item 4 is the cheapest and simplest solution to the challenge: Carry paper charts. It can’t hurt to have at least a relatively recent sectional, the local approach plates and a low altitude en route chart in my seat’s back pocket.

Eggs And Baskets

At the end of the day, my overheated iPad was a minor glitch in an uneventful few days of flying. I had a backup to the charting and aeronautical data I needed, that backup worked flawlessly and the outcome was never in doubt. The backup system got me home with no additional fuss or bother. I love it when a plan comes together.

My temporary EFB outage had no operational impact, and I suffered no loss of situational awareness. In the plane’s panel, I already had a moving map, the traffic and weather of the FAA’s ADS-B data stream and current aeronautical data. But I can get by without that stuff, too, especially on a short flight in good visual conditions.

Without a backup, we can still get by in a pinch without the information charts supply and which I mostly lost when the iPad overheated. Over familiar routes in visual conditions, pilotage and ded reckoning don’t require batteries or software updates and work well. I can—and should!—look out the window for traffic avoidance and to assess the weather. Even when you’re having a really bad day and find yourself IFR without a chart, ATC can relay what you need to know. You won’t endear yourself to anyone on the frequency, but you’ll get down safely. I’ve had to ask for some of that data after a pre-tablet EFB experiment of mine failed miserably.

Crisis? What Crisis?

Losing the functionality and features of a modern EFB should not be an in-flight crisis. If you can’t safely complete the flight after sustaining an EFB failure, there’s something wrong with your planning and equipment choices. Reverting to VOR for navigation, for example, shouldn’t result in getting lost.

On the other hand, if you’re using your consumer-grade tablet and commercial EFB software as the sole reference to tactically circumnavigate a line or cluster of thunderstorms in IMC, you’re doing it wrong. Likewise, if you were depending on it to safely navigate around airspace or between canyon ridges at night. Losing the EFB in these situations can paint you into a corner, but you should have thought about that before agreeing to the decision chain that got you there.

A lot of the discussion about pilots becoming overdependent on EFBs that arose when they first became reliable and functional has subsided with time. Part of the reason for that is widespread acceptance of their inevitable utility, coupled with a clear-eyed training community that isn’t afraid to turn it off and see how the student reacts. That said, doing without an EFB’s functionality may place a relatively new pilot—one who grew up on moving maps and near-real-time Nexrad, for example—at a distinct disadvantage. Turning off the EFB and doing it old-school isn’t something a prepared pilot should fear.

Are pilots overdependent on their EFBs? Some probably are, and they won’t really understand how dependent they’ve become until it fails some dark and stormy night. They likely haven’t trained much lately, or had a thoughtful instructor. The punch line is the EFB’s information and functionality shouldn’t be the only arrow in our situational awareness quiver: We shouldn’t let our EFB lead us into situations where an untimely failure can jeopardize the flight.

If it does, that’s on you. There typically are enough options and backups present in modern panels to get you home. But it never hurts to carry a paper chart or two.

Which Part of ‘Consumer-grade’ do you not understand?

Today’s popular EFB software predominately runs on hardware developed and sold worldwide as consumer items. That’s a good thing, overall, since competition allows us to have the latest and greatest display and communication devices far more often than is practical when considering installed equipment alone. But it’s not without downsides. Over my long-term use of portable devices in the cockpit, there’s always been at least one instance when they “fell down.”

We can’t forget that any consumer-grade device will not be as robust as an FAA-approved product. All things considered, a modern tablet running an EFB app is far preferable to many of the other options presently available for the same functionality. But it’s not bulletproof, and we all should have a plan for when it fails.

This should be a no-brainer. Without some kind of mount, it won’t be where you expect it and can be damaged, rendering it useless.

Running an EFB on its internal battery alone is a bad idea since you never know when you might have to rely on it. Power bricks are handy backups.

The most useless EFB is the one in your luggage. Pull it out, mount it, power it, boot it and program it before releasing the brakes to taxi.

Some platforms seem to have a constant update cycle. Between the OS, the publication update cycle and the EFB app itself, there’s always something to download and install.

When trying and failing to use an EFB’s automation, the best choice might be to simply put it aside and fly the airplane as you did before EFBs.

Jeb Burnside is this magazine’s editor-in-chief. He’s an airline transport pilot who owns a Beechcraft Debonair, plus the expensive half of an Aeronca 7CCM Champ.